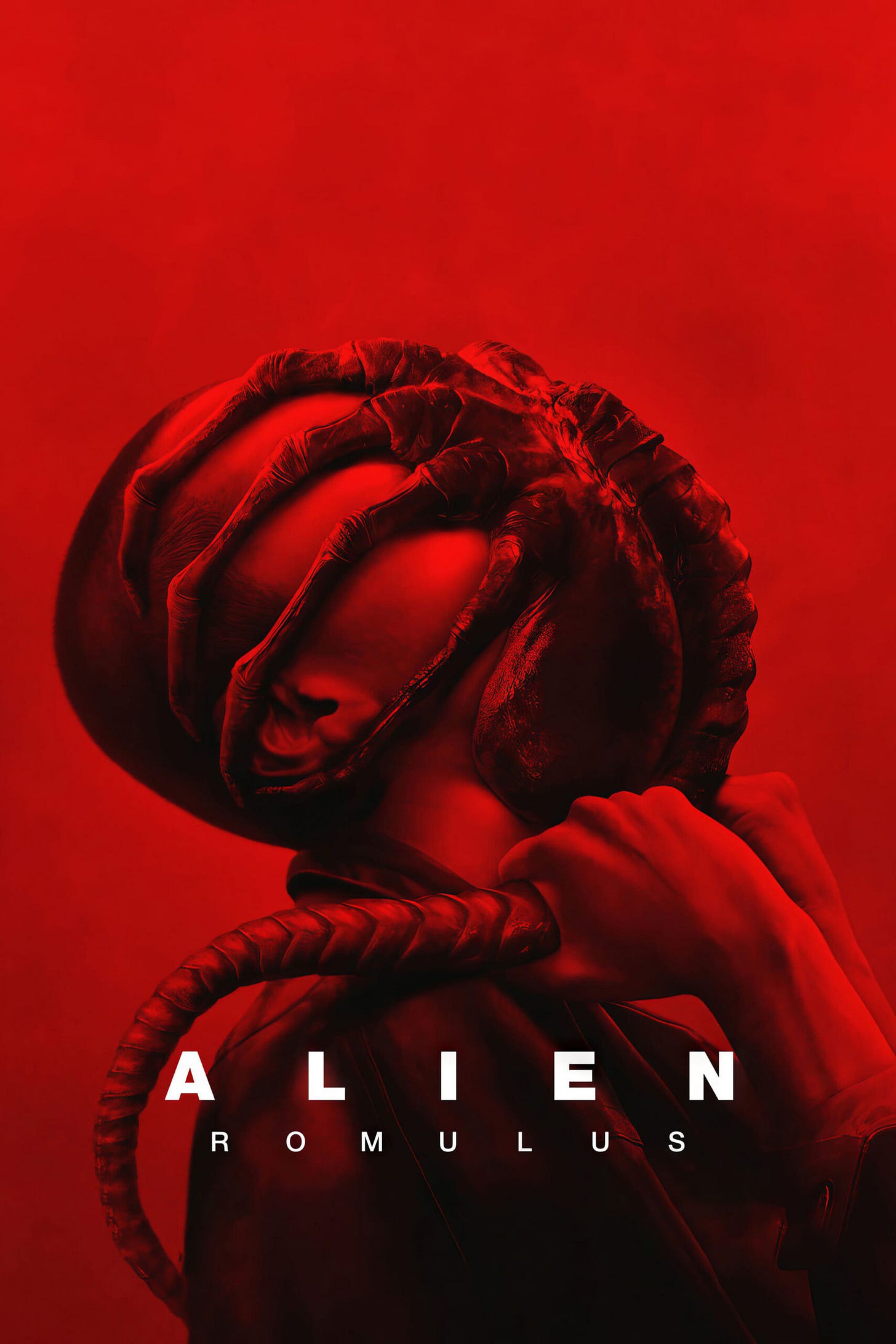

Alien: Romulus (2024)

Ode to the Xenomorph.

The Greatest Creature Ever Featured

“You still don't understand what you're dealing with, do you? The perfect organism. Its structural perfection is matched only by its hostility… I admire its purity. A survivor: unclouded by conscience, remorse, or delusions of morality. I can't lie to you about your chances, but... you have my sympathies.”

-Ash, on the Xenomorph, in Alien (1979)

Alien: Romulus, the series’ seventh installment directed by Fede Álvarez, is a thrilling romp through a derelict Weyland Corp research vessel infested with the titular intergalactic parasites. It’s a crowd-pleasing film that returns to Alien’s roots in survival horror but also delivers the heightened spectacle of Aliens (1986).

It’s a throwback to the claustrophobic ambiance and narrative sensibilities of the original films that also continues exploring the themes of creation and evolution foregrounded in Scott’s 21st-century installments to the franchise, Prometheus (2012) and Alien: Covenant (2017).

A contingent of critics and audiences has expressed ambivalence towards Alien: Romulus, which they regard as a “legacy sequel.” The criticisms are warranted; the film is riddled with explicit references to previous films.

The most shameless displays of fan service garnered applause in my theater, but my eyes were too busy rolling into the back of my skull for me to slap my appendages together in a reflexive celebration of familiarity.

Countless, less obtrusive references to earlier entries didn’t irk me as much. Ultimately, the film’s preoccupation with the past proves to be a mixed bag.

There are a couple of novel setpieces, but Alien: Romulus is akin to a greatest hits album from your favorite band. It offers the essence of what you know and love, remastered and remixed enough to justify its own reproduction.

At some point during Alien: Romulus, it did occur to me that all Alien films are structurally identical. I’ve been a fan of Alien since I was eight years old. Eighteen years later, I found myself in the theater on Alien: Romulus’ opening day. What keeps me coming back?

It’s the Xenomorph, the greatest creature to ever be featured in a creature feature.

On the Xenomorph

“Alien is a radical break with science fiction. This is not the notion of the alien we were building toward in something like [Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977)].

-Henry Jenkins, Provost Professor of Communication, Journalism, Cinematic Arts & Educations at USC, quoted in Memory: The Origins of Alien (2019)

“We’re looking at a story where there is a piece of material prop that is now completely alive in our imaginations. It lives in our dreams. It lives in our cultural conversation. It’s one of the biggest cultural dreams we’ve ever had.”

-William Linn of the Joseph Campbell Writers' Room at Studio School, quoted in Memory: The Origins of Alien (2019)

Over forty-five years after Ridley Scott’s Alien debuted on the big screen, forever changing the science fiction genre, the Xenomorph remains a terrifying, formidable foe for new crews of unsuspecting astronauts.

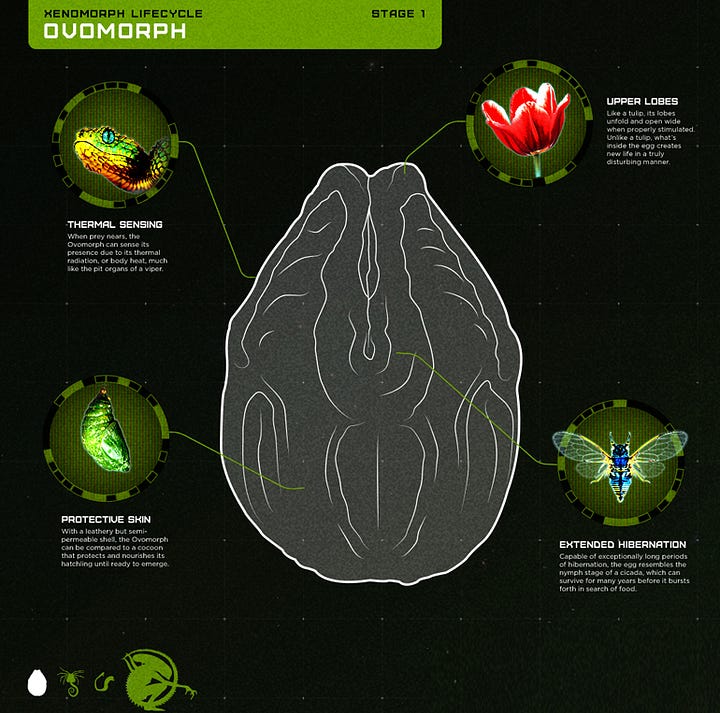

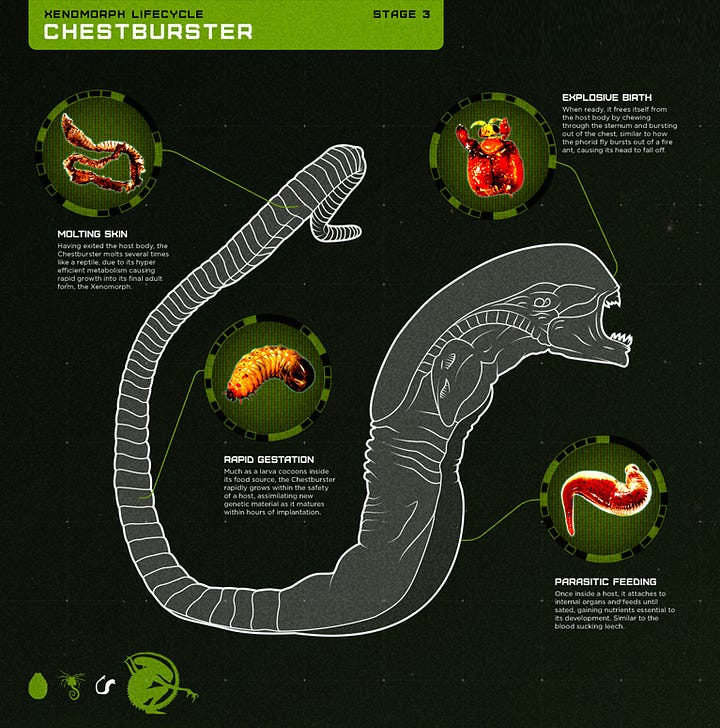

It began in the mind of Dan O’Bannon, who had written the first third of what would eventually become the screenplay for Alien. According to O’Bannon’s widow, he was inspired by his Chron’s disease, which felt like he was being eaten from the inside. He also feared bugs, and he was particularly fascinated with parasitic wasps.

“There are over a million species of parasitic wasps. That means of all the animals in the animal kingdom, the number one form of animal is a parasitic wasp. There are wasps that like to make caterpillars their host… everything [the host] eats is going to feel these larvae that are growing inside its body cavity… once those wasps are ready, they just blast their way out of their host… If that’s lethal to the host, fine… getting inside something else and feeding on it from within is a really great way to survive and evolve. The alien is just fitting into this fundamental basic pattern that you find in life, probably the most successful way to be alive on Earth.”

-Carl Zimmer, New York Times columnist and author of ‘Parasite Rex,’ quoted in Memory: The Origins of Alien (2019)

To continue developing his idea, O’Bannon turned to Ron Shusett, whose work earned him a story credit on the final film. He helped answer O’Bannon’s most vexatious question: how would the alien get back on the ship? Shusett had a breakthrough:

“I went to sleep, and I’m aware it wasn’t dreaming. It was something else. It was when your mind is in the subconscious. I was wrestinling with a property in my sleep. I woke [O’Bannon] up, I went right into his studio and I said, ‘I have it.’

He said, ‘What? You have the answer?’

I said, ‘I have the answer. The alien fucks him.’

He said, ‘What? What are you talking about?’

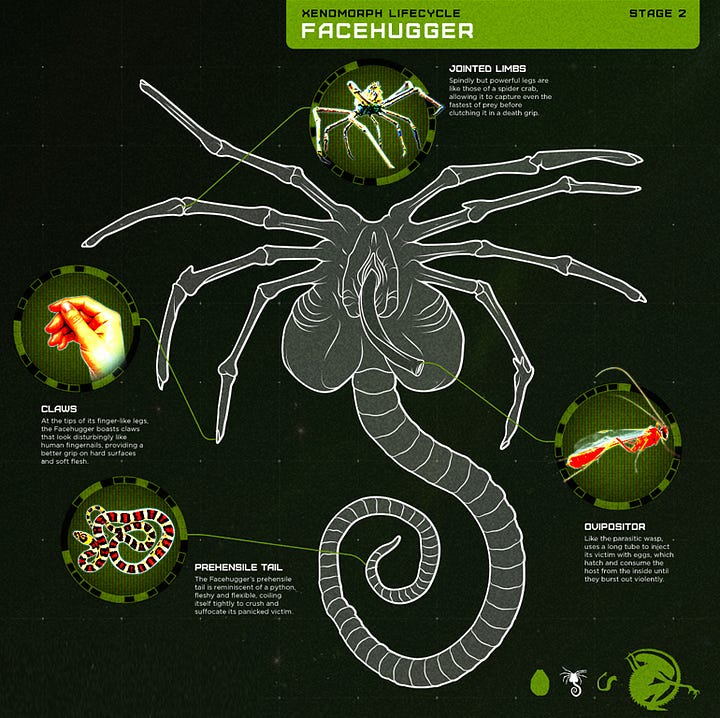

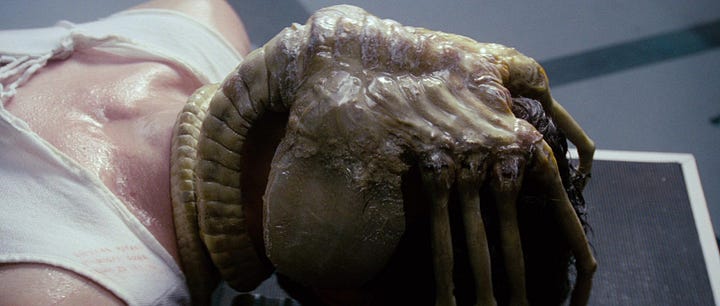

I said, ‘It jumps on his face, it’s a little creature then, little baby squid-like, sticks a tube down his throat, starts feeding him air, but he’s implanting his seed. And it’s going to grow inside him and burst out of his chest in the middle of the movie!”

-Ron Shusett, quoted in Memory: The Origins of Alien (2019)

And so it was that the Xenomorph gained its most essential and distinctive characteristic. It is a creature whose very nature is predicated on bodily violation. Here is a beast that orally rapes its victims and implants an embryo that will eventually exit its host’s ‘womb’ in a violent, bloody fashion.

It abstracts the horrors of sexual violence perpetrated against women and inflicts that bodily horror upon male bodies within a genre with a strong male fanbase.

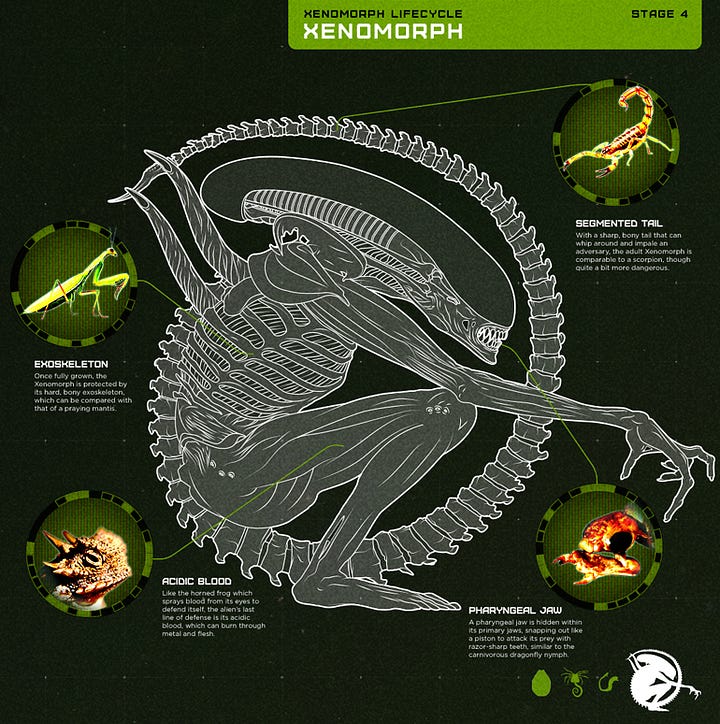

Every detail of the Xenomorph’s design is a psychosexual attack on the viewer's psyche: in infancy, it is a smothering hand that skitters like a spider and inserts a phallus deep into the victim’s throat. It exits its host in an explosive, bloody rending of flesh that visually evokes the bodily trauma of birth. It’s post-natal form is phallic, essentially a penis with teeth. In its final form, the Xenomorph has a phallic-shaped head, a spiked tail (also phallic), and a retractable inner jaw that penetrates flesh (very phallic).

“…there’s no way of looking at Alien without seeing it as a male fantasy of oppression… handed out to women over the centuries, a guilt that was part of masculinity in the 1970s, and should be a part of masculinity now. Alien has within it fantasies of male pregnancy, fantasies of male rape, fantasies of male penetration… It’s all tied up with that amazing chest-burster scene.”

-Micheal Peppiatt, author of ‘Francis Bacon in Your Blood,’ quoted in Memory: The Origins of Alien (2019)

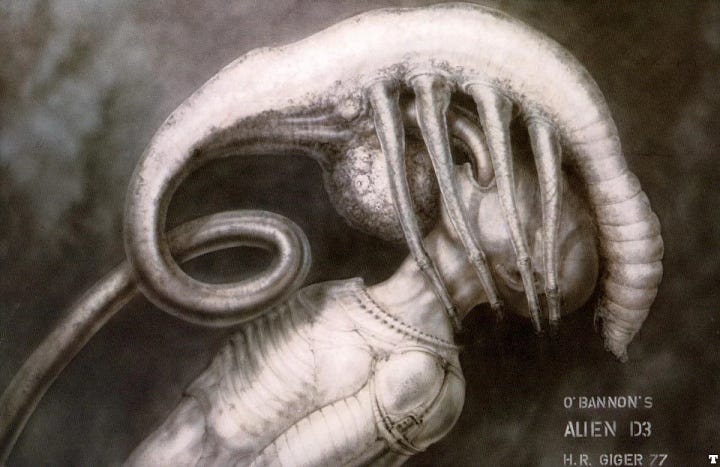

Call H.R! Get me Giger!

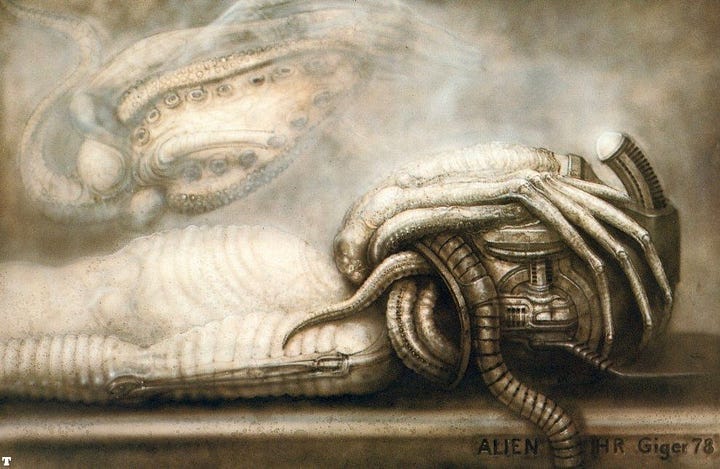

Ultimately, it was H.R. Giger, a brilliant, twisted Swiss artist, whose artistic talents would give the monster its final form. His signature aesthetic reveals a Lovecraftian fascination with monsters beyond human comprehension.

“Giger consolidates every monster from every mythology around the world into a single creature. He embodies the mythic other.”

-Henry Jenkins, Provost Professor of Communication, Journalism, Cinematic Arts & Educations at USC, quoted in Memory: The Origins of Alien (2019)

“Giger was a mystic. He had his own mythology, his own cosmology. He took like a bee from different flowers to feed his imagination and make his own honey…”

-Bijan Aalam, H.R. Giger’s friend and gallerist, quoted in Memory: The Origins of Alien (2019)

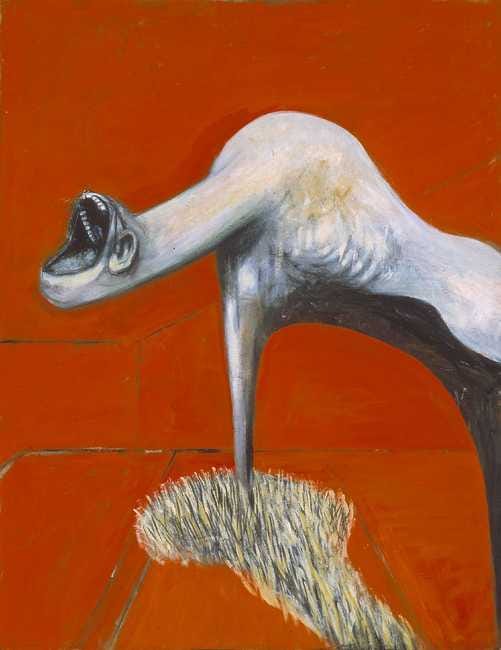

Giger assembles his horrifying bouquet from Egyptian mythology and imagery, the cosmic horror of H.P. Lovecraft, and artists like Hieronymus Bosch and Francis Bacon.

The results are a “fantastic, sexual, mechanical, biological amalgamation” that is utterly singular and supremely disturbing, so much so that upon seeing Giger’s work, executives at Fox Studios deemed him a depraved sicko and fired from the project.

When director Ridley Scott joined the production, he was floored by Giger’s work and became an essential advocate for Giger’s vision for the project. In an interview, a young Ridley Scott recounts O’Bannon sharing Giger’s Necronomicon: “I nearly fell off the desk. Said, that’s it. And why look further? … It was as simple as that. I’ve never been so certain about anything in my life.”

Many years later, Scott would say in another interview, “I just thought it was stunning, and I just stuck to my guns saying… No, that’s it… Just to get this right is gonna be incredibly difficult. This is beautiful, not just threatening, and also has very sexual connotations. So in everything, it’s like a rather beautiful humanoid biomechanoid insect.”

“Alien touched a nerve with a lot of people because it was talking about something that, even in 2019, we’re still not comfortable addressing.”

-Clarke Wolfe of “Sending the Wolfe” Podcast, quoted in Memory: The Origins of Alien (2019)

The creative quartet of O’Bannon, Shusett, Giger, and Scott synergized and synthesized cinema’s most terrifying beast. It’s a parasitic insectoid driven by primal urges that evoke the ugliest facets of mankind. It’s a demon plumbed from our festering, collective subconscious that visually repulses, physically violates, and remains as viscerally upsetting in 2024 as ever.

Forty-five years after the Xenomorph’s birth, with technical advancements and eight times the original Alien’s budget, Alien: Romulus is a spectacular showcase of the greatest creature to ever be featured, with the potential to delight and disgust Xenomorph enthusiasts old and new.

At the end of Alien: Romulus, I heard a child no older than six say, “Daddy, that was scary.” He held his father’s hand as they exited the theater, and he mumbled a question about the alien being in his house. I wondered if Alien Romulus would be a source of trauma or fascination for that child. If he’s anything like me at that age, it will be both.

Until next week, pray that the child in my theater is doing okay, my fellow film freak.