Civil War is Not Apolitical

“Every time I survived a war zone, I thought I was sending a warning home: ‘Don’t do this.’ But here we are.”

-Lee Smith (Kirsten Dunst), a war photographer, in Civil War.

Alex Garland’s Civil War, an inflammatory work of speculative fiction that explores what a second civil war might look like in the United States, has provoked disparate reactions among critics and audiences alike. Civil War is not a perfect film, but it is a powerful film. There is not a single scrap of joy to be had in Alex Garland’s Civil War. In the violent spectacle there lies only horror and anguish.

Civil War may not be a “good time at the movies” in any traditional sense, but maybe we don’t always deserve a pleasant evening at the cinema. Maybe escapism is the last thing we need right now. Alex Garland seems to think so, and I am inclined to agree.

A film as abrasive as Civil War won’t cater to everybody’s tastes, and negative reviews are to be expected. However, I have been utterly vexed by the chorus of criticism which damns Civil War as a work of irresponsible, apolitical opportunism. I am left to wonder, did we watch the same film?

Many have noted the lack of exposition regarding Civil War’s military conflict, and interpret that absence as artistic cowardice. In failing to explore the roots of a speculative civil war, detractors assert that Civil War is opting to say nothing of substance besides “war is bad.”

The political landscape of the film’s conflict remains unclear, we are never told why Texas and California have seceded, and that might make the film’s politics seem muddled or underdeveloped. In truth, the abstraction is a feature, not a flaw.

Everything about Civil War, its imagery and speculative conflict, unfold within the very real context of American history. Viewers lost in Civil War’s political abstraction should heed these wise words:

Alex Garland, born in London, does not seek to imbue his film with the partisan rancor of American politics. His film is not a polemic about the 2024 election cycle.

As a film, Civil War is not equipped to grapple with why America has turned on itself. I can’t fathom an answer that I would find satisfactory, and so it’s best left undefined. Sometimes a question is more interesting than the answer.

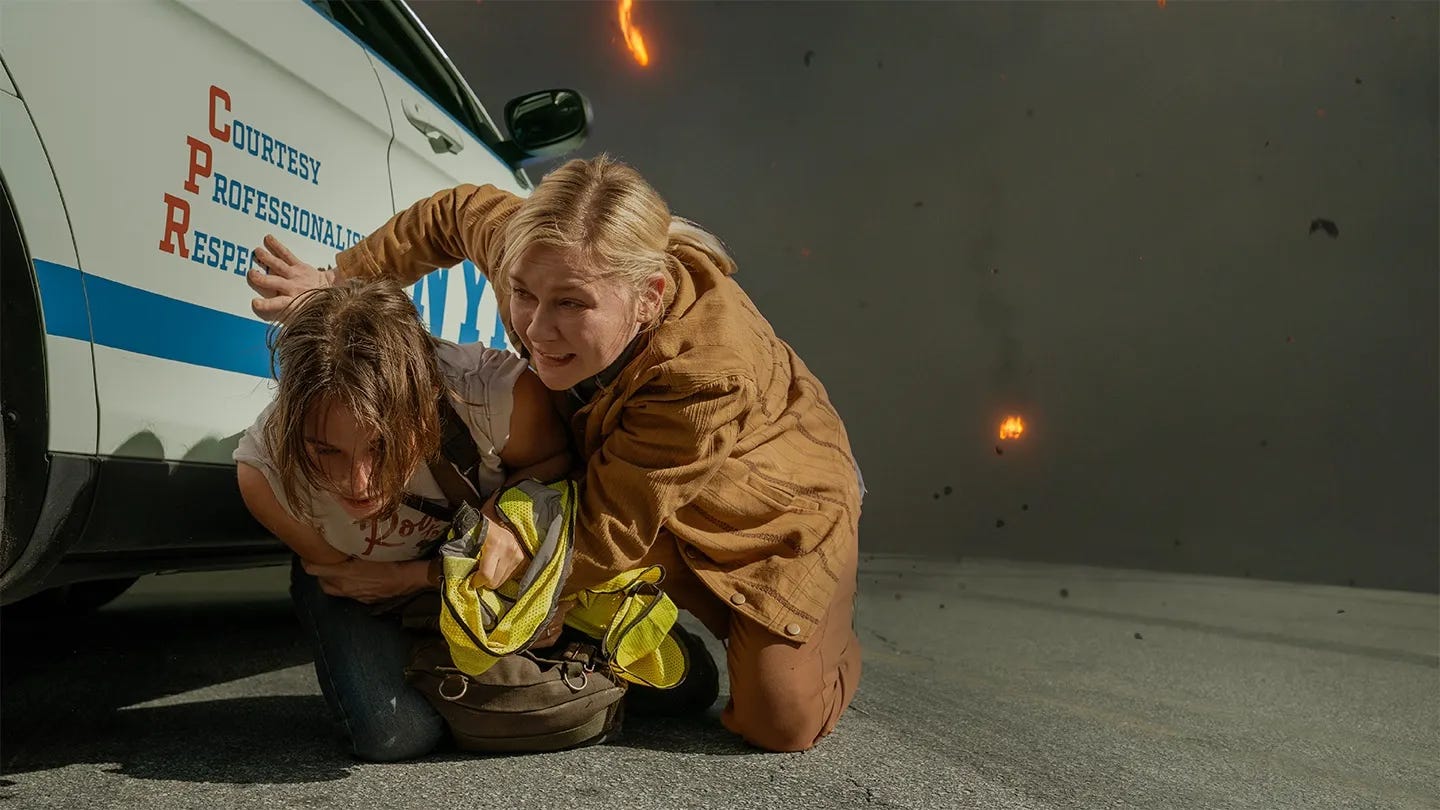

Rather, Civil War is a film explicitly interested in how such a conflict would look and feel. On that front, the film is tremendously successful. Civil War follows a group of photographers and journalists on a journey from New York to the conflict’s front lines.

Civil War’s protagonist could’ve been a soldier, but that would run the risk of valorizing the acts of war. Garland doesn’t orient his film around combatants. Instead, it is about journalists. Civil War is not concerned with the fighting of a war, it is focused on what war looks like to the observer. It’s a film that begs to be put in dialogue with Susan Sontag’s 2003 essay, “Regarding The Pain Of Others.”

Sontag’s essay, which you can read in its entirety, is a historical and theoretical examination of war photography: its development, its function, and the nuances and contradictions intrinsic to the medium of photography.

“…photographs of the victims of war are themselves a species of rhetoric. They reiterate. They simplify. They agitate. They create the illusion of consensus…”

“The photographs are a means of making ‘real’ (or ‘more real’) matters that the privileged and the merely safe might prefer to ignore.”

“Look, the photographs say, this is what it's like. This is what war does. And that, that is what it does, too. War tears, rends. War rips open, eviscerates. War scorches. War dismembers. War ruins.”

“But is it true that these photographs, documenting the slaughter of noncombatants rather than the clash of armies, could only stimulate the repudiation of war? Surely they could also foster greater militancy … Isn't this what they were meant to do?”

“If governments had their way, war photography, like most war poetry, would drum up support for soldiers' sacrifice. Indeed, war photography begins with such a mission, such a disgrace.”

-Excerpts from “Regarding the Suffering of Others” by Susan Sontag

Film and photography are distinct but related mediums. Cinema is a technological evolution of photography, and while war photographs and war films do not serve the same function generally, Garland’s Civil War is a war film that directly imbricates war photography, and it does so intentionally.

As a result, Sontag’s insights into photography resound throughout the film, and perhaps some of her insights can be extrapolated into the realm of cinema. In this way, the artistic goals of Garland’s Civil War begin to overlap with those of its characters.

“…there are many uses of the innumerable opportunities a modern life supplies for regarding—at a distance, through the medium of photography—other people's pain. Photographs of an atrocity may give rise to opposing responses. A call for peace. A cry for revenge. Or simply the bemused awareness, continually restocked by photographic information, that terrible things happen.”

“Being a spectator of calamities taking place in another country is a quintessential modern experience, the cumulative offering by more than a century and a half's worth of those professional, specialized tourists known as journalists. Wars are now also living room sights and sounds. Information about what is happening elsewhere, called ‘news,’ features conflict and violence… to which the response is compassion, or indignation, or titillation, or approval, as each misery heaves into view.”

“Awareness of the suffering that accumulates in a select number of wars happening elsewhere is something constructed. Principally in the form that is registered by cameras, it flares up, is shared by many people, and fades from view. In contrast to a written account—which, depending on its complexity of thought, reference, and vocabulary, is pitched at a larger or smaller readership—a photograph has only one language and is destined potentially for all.”

-Excerpts from “Regarding the Suffering of Others” by Susan Sontag

Seen through this lens, the decision not to provide explicit political context to Civil War’s conflict is a choice that actively frustrates the audience’s ability to politically identify with the events they witness onscreen. As a viewer looking through the war photographer’s camera, your personal and political views work against the (theoretically) objective medium of war photography.

“In a system based on the maximal reproduction and diffusion of images, witnessing requires the creation of star witnesses, renowned for their bravery and zeal in procuring important, disturbing photographs.

War photographers inherited what glamour going to war still had among the anti-bellicose, especially when the war was felt to be one of those rare conflicts in which someone of conscience would be impelled to take sides.”

“The photographer's nationality and national journalistic affiliation were, in principle, irrelevant. The photographer could be from anywhere.”

-Excerpts from “Regarding the Suffering of Others” by Susan Sontag

The supposedly objective nature of photography is illusory. The person behind the camera frames the image. In the composition of images, point of view cannot be avoided. The same can be said about cinema. Garland’s film has a point of view that is very explicitly and intentionally tied to the experience of war photographers. This creative and narrative decision comes with all the contradictions inherent to war photography.

“…to ask that images be jarring, clamorous, eye-opening seems like elementary realism as well as good business sense. How else to get attention for one's product or one's art? How else to make a dent when there is incessant exposure to images, and overexposure to a handful of images seen again and again? The image as shock and the image as cliche are two aspects of the same presence.”

“Photographs had the advantage of uniting two contradictory features. Their credentials of objectivity were inbuilt. Yet they always had, necessarily, a point of view.”

“This sleight of hand allows photographs to be both objective record and personal testimony, both a faithful copy or transcription of an actual moment of reality and an interpretation of that reality - a feat literature has long aspired to, but could never attain in this literal sense.

Those who stress the evidentiary punch of image-making by cameras have to finesse the question of the subjectivity of the image maker. For the photography of atrocity, people want the weight of witnessing without the taint of artistry, which is equated with insincerity or mere contrivance.”

“Whether the photograph is understood as a naive object or the work of an experienced artificer, its meaning – and the viewer's response - depends on how the picture is identified or misidentified; that is, on words…”

-Excerpts from “Regarding the Suffering of Others” by Susan Sontag

Garland is well aware of the power of images and the way they mediate a non-combatant’s perception of atrocity. Early in the film, the NYC skyline, prominently featuring One World Trade Center, is dotted with plumes of black smoke. It is a very deliberate evocation of 9/11, a collective atrocity that shook American society to its core and, ironically, caused Americans to “rally around the flag.” It is just one example of the ways that Civil War is political without spoonfeeding viewers “the point of it all.”

In 2024, Garland is able to draw upon American history’s most recent experience of domestic war, and a robust understanding of how people process atrocities beyond their comprehension.

“…battles and massacres filmed as they unfold have been a routine ingredient of the ceaseless flow of domestic, small-screen entertainment. Creating a perch for a particular conflict in the consciousness of viewers exposed to dramas from everywhere requires the daily diffusion and rediffusion of snippets of footage about the conflict. The understanding of war among people who have not experienced war is now chiefly a product of the impact of these images.

Something becomes real—to those who are elsewhere, following it as ‘news’—by being photographed. But a catastrophe that is experienced will often seem eerily like its representation. The attack on the World Trade Center on September 11 2001, was described as ‘unreal,’ ‘surreal,’ ‘like a movie,’ in many of the first accounts of those who escaped from the towers or watched from nearby. (After four decades of big-budget Hollywood disaster films, ‘It felt like a movie’ seems to have displaced the way survivors of a catastrophe used to express the short-term unassimilability of what they had gone through: ‘It felt like a dream.’)”

-Excerpts from “Regarding the Suffering of Others” by Susan Sontag

I believe that Garland’s Civil War is well aware of its inflammatory nature, and the film works hard to render a vivid and uncompromising nightmare of domestic dissolution without indulging in the suffering of others as an entertaining spectacle. Garland’s film and the strong violence it includes are gruesome provocations crafted with intention and begs complex ethical consideration.

“There [is] also the repertoire of hard-to-look at cruelties … No moral charge attaches to the representation of these cruelties. Just the provocation: can you look at this? There is the satisfaction of being able to look at the image without flinching. There is the pleasure of flinching.”

“An invented horror can be quite overwhelming… But there is shame as well as shock in looking at the close-up of a real horror. Perhaps the only people with the right to look at images of suffering of this extreme order are those who could do something to alleviate it—say, the surgeons at the military hospital where the photograph was taken—or those who could learn from it. The rest of us are voyeurs, whether or not we mean to be.

In each instance, the gruesome invites us to be either spectators or cowards, unable to look.

Those with the stomach to look are playing a role authorized by many glorious depictions of suffering. Torment, a canonical subject in art, is often represented … as a spectacle, something being watched (or ignored) by other people. The implication is: no, it cannot be stopped—and the mingling of inattentive with attentive onlookers underscores this.”

-Excerpts from “Regarding the Suffering of Others” by Susan Sontag

Civil War confronts viewers with an all-too-plausible rendering of America polarized to the point of violent rebellion. To reject the film as apolitical cowardice due to insufficient political transparency surrounding the cause of Civil War’s civil war strikes me as facile. You’re missing the forest for the trees.

If Civil War offered enough context for viewers to anchor their values and, as a result, determine the “good guys” from the “bad guys,” it would negate the entire ethos of Garland’s film. The film doesn’t abstract its political conflict for narrative convenience or expedience. To know what preempted Garland’s Civil War can only serve to muddle the film’s point of view — a point of view intentionally detached from real-world political identities.

Our understanding of a conflict is unavoidably mediated through subjective experiences rooted in personal identities. Who we are is essential to our perception of events and how we parce “right” from “wrong.” In the bloody moral ambiguity of Civil War, it's only natural to try and politically orient oneself within the film. Without this, critics assert, Civil War says nothing.

I couldn’t disagree more. Civil War only works in the realm of political abstraction. An overtly accessible political background would only make Civil War divisive for different, less productive reasons.

“To those who are sure that right is on one side, oppression and injustice on the other, and that the fighting must go on, what matters is precisely who is killed and by whom. To an Israeli Jew, a photograph of a child torn apart in the attack on the Sbarro pizzeria in downtown Jerusalem is first of all a photograph of a Jewish child killed by a Palestinian suicide-bomber. To a Palestinian, a photograph of a child torn apart by a tank round in Gaza is first of all a photograph of a Palestinian child killed by Israeli ordnance. To the militant, identity is everything. And all photographs wait to be explained or falsified by their captions… Alter the caption, and the children's deaths could be used and reused.”

-Excerpts from “Regarding the Suffering of Others” by Susan Sontag

Civil War’s conflict does not have context. It does not come with a convenient caption to help you process the on-screen horrors. Such simplicity would muddy the complicated questions of Garland’s film, which takes aim at our individual relationships to the idea of war and our willingness to regard political violence as a viable method of effectuating change, whatever that change may be.

“Photographs of mutilated bodies certainly can be used … to vivify the condemnation of war, and may bring home, for a spell, a portion of its reality to those who have no experience of war at all. However, someone who accepts that in the world as currently divided war can become inevitable, and even just, might reply that the photographs supply no evidence, none at all, for renouncing war- except to those for whom the notions of valor and sacrifice have been emptied of meaning and credibility. The destructiveness of war… is not in itself an argument against waging war unless one thinks (as few people actually do think) that violence is always unjustifiable, that force is always and in all circumstances wrong— wrong because … violence turns anybody subjected to it into a thing. No, retort those who in a given situation see no alternative to armed struggle, violence can exalt someone subjected to it into a martyr or a hero.”

-Excerpts from “Regarding the Suffering of Others” by Susan Sontag

Without context or justification, how do you process Civil War’s conflict? Civil War places political violence in the driver’s seat. As a viewer, Garland renders you a passenger, but it is not a passive viewing experience. You are asked to bear witness to ghastly sights and cope with their plausibility.

To provide context to Civil War’s conflict would risk turning Garland’s film into the very thing it seeks to rebuke. There is no heroism on display in Civil War, and its displays of martyrdom are not blazes of glory. They are deaths devoid of grandiose meaning and have no bearing on the unfolding conflict.

There are no martyrs, only casualties. There is no glory, only grief.

“Normally, if there is any distance from the subject, what a photograph ‘says’ can be read in several ways. Eventually, one reads into the photograph what it should be saying,”

-Excerpts from “Regarding the Suffering of Others” by Susan Sontag

To viewers who remain unsatisfied by the politics of Garland’s film, I would ask: what do you think Civil War is trying to say? More importantly, what do you believe it should say?

Until next week, God save America, film freak.

I think that the politics of the movie are implicit but not *that* implicit. The President is Trump, he seized dictatorial power; the forces resisting him are probably justified (they are slightly "queer-coded" and are sympathetic to the press) but have been so brutalized by the civil war they are likely not an improvement; we are expected to be thrilled when pseudo-Trump is summarily executed but then feel guilty and interrogate our reaction to what we've seen.

The movie just leaves out a bunch of the middle steps that lead from pseudo-Trump being elected to the last stages of the civil war, and with slightly unrealistic literalness it makes the US civil war strongly resemble recent foreign civil wars so that its visual style can mimic press coverage of those wars.

Skylar--this is such a perceptive commentary on Civil War, which I just saw yesterday. I haven't read Sontag's essay before, so that's a fresh lens on the subject of war photography. I'll need to read the whole essay soon. It seems to me that most reviews are ignoring the film's true subject: the role of the conflict photojournalist and the trauma/ethics associated with their work (both in front of and behind their cameras). I found the film as disturbing as you did and agree that it's political -- not in terms of the cause of the civil war or its different ways of fighting -- but in terms of what we are to make of the images these photojournalists take and what they ask us to do in response to them.

The real question, it seems to me, is can these photojournalists justify the risks they take and the violence that they feed off of. It's important that Garland stops every now and then to show them at rest or absorbing the beauty of nature and human life amid even the worst carnage. They do have souls and they do suffer (each of the main journalists portrayed here suffer a breakdown of sorts at various points of the film), even as they carry on at all costs. When Moura's character says the violence is giving him a hard-on, it's the surface, macho posing we sometimes associate with these kinds of vultures, but underneath that we can see the toll it takes on him until he's is consumed with grief and terror (the image of him screaming silently as the military trucks roll by is particularly searing).

On a separate note, I want to highlight how good Cailee Spaeny is in her role as the fledging photojournalist. Spaeny has a presence and sweetness (and vulnerability) that makes me excited for her future as an actress. I haven't seen Priscilla yet, but I was impressed with her work with Dunst throughout the film.