Help, My Childhood Has Become a Period Piece!

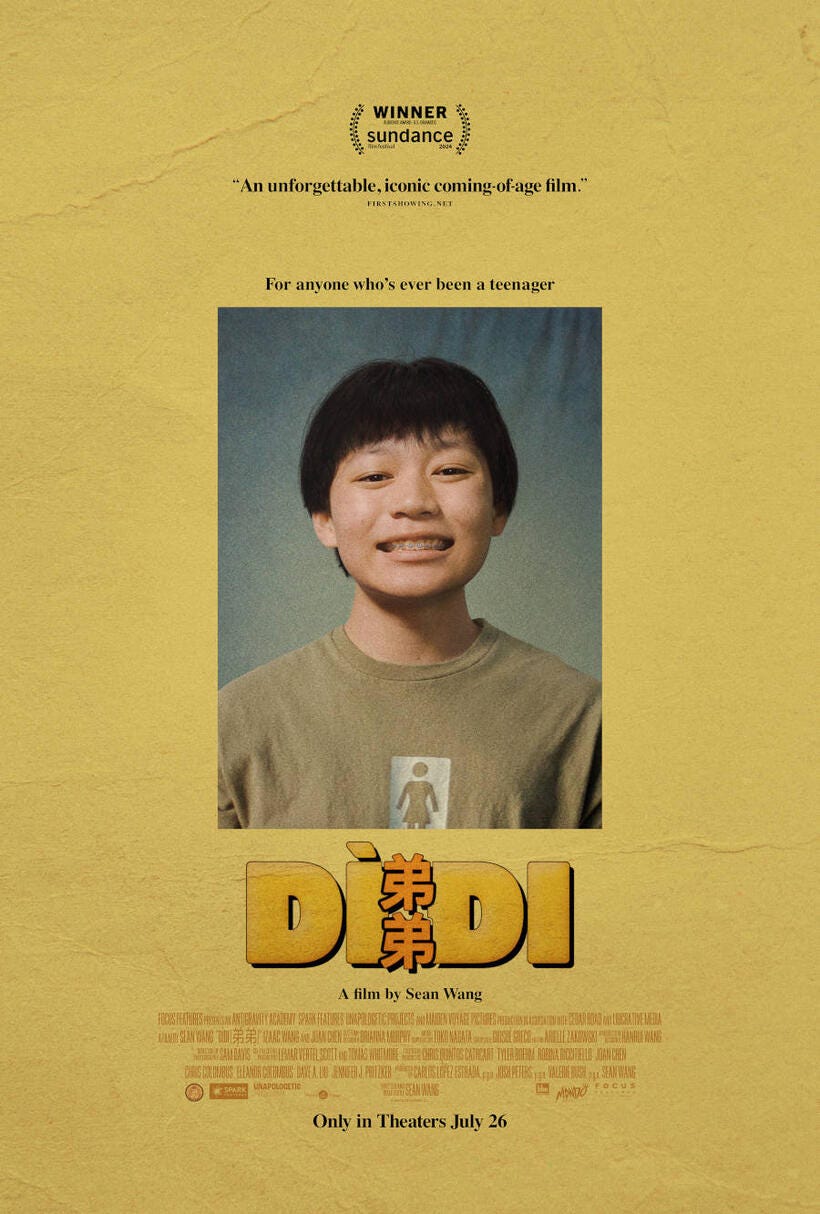

Set in August of 2008, Dìdi is a semi-autobiographical work from writer/director Sean Wang, that follows Chris Wang (Izaac Wang): a 13-year-old boy (known as “Dìdi” among family and “Wang Wang” among his friends) as he navigates growth, transition, and upheaval in his final month of summer before high school begins. In the era of A.I.M., flip phones, and T9 texting, Dìdi struggles to find and situate his sense of self within his evolving social group and a developing conception of masculinity.

It is a pitch-perfect coming-of-age film that renders the socio-emotional growing pains of adolescence in the mid-aughts in a manner that is as outrageously entertaining as it is tender and earnest. It captures the dejection of growing apart from old friends, the exultation of finding new places to fit in, and new ways to be appreciated and to appreciate others.

Bolstered by naturalistic performances from a stellar cast of young actors, Dìdi’s interactions with his peers feel true to life. Sex is a perennial topic of conversation, with the boys lying to each other in the way that teenage boys always do. Every boy positions themselves as the expert only to be humbled by the painfully awkward realities of interacting with the opposite sex. In their attempts to act like adults, they exude immaturity.

In an early scene, a friend casually tells Chris his cargo shorts are “gay.” Chris retorts that Lil Wayne wears them. “Then Lil Wayne is gay,” his friend replies. Chris insists that everyone wears cargo shorts. “Well, then everyone’s gay,” his friend concludes, the unassailable confidence of youth overshadowing the fact that they don’t truly understand what they’re saying. Their rapport is insensitive yet endearing.

In small but significant ways, August 2008 proves to be a moment of major transition in Dìdi’s life. His older sister is preparing to leave for college, a change in the family dynamic whose ripple effects evoke the specter of Dìdi’s own maturation, which looms, inevitable yet still out of reach. As things in his life begin to change, a sense of transience clashes with exasperating stasis as Dìdi works to find his footing in the painfully awkward present. Transience is both a source of comfort and anguish: a reassurance that this too shall pass, but that this moment will never come again.

Within the coming-of-age genre, Dìdi walks a well-trodden path. It all but demands comparison to recent entries like Bo Burnham’s Eighth Grade (2018) and Jonah Hill’s Mid-90s (2019). Cut from the same cloth, all three offer poignant portraits of adolescence situated at different moments in time, but Dìdi is far and away my favorite. Perhaps it is because I am a Zellenial, and Dìdi, set in 2008, most directly reflects what my adolescence looked like.

I see a lot of myself in Mid-90s, but the film’s temporal specificity pre-dates my own coming-of-age. It is an ode to the last generation to grow up without technology attached to their hip. I was not among those last lucky few.

On the other hand, Eighth Grade’s foregrounding of social platforms like Instagram and Snapchat reflects a relationship between technology and adolescence that feels distinctly Gen-Z, with a cautionary message that can feel obvious and preachy. Those platforms certainly existed when I was in high school, but they had yet to become a dominant mode of social engagement.

Dìdi’s technological landscape of MySpace, early Facebook, and O.G. YouTube is where I grew up. In retrospect, it seems technology was also a period of transition. It was the beginning of constant online performance. The advent of online social platforms allowed new forms of individual expression, but they had yet to metastasize into the toxic hellscapes of omnipresent inadequacy we have come to know all too well. Dìdi recreates the moment, tapping into a sense of innocence that would, in time, reveal itself to be transient, wishful naivete.

Furthermore, where Hill and Burnham’s films featured white protagonists, Wang imbues his film with a beautiful cultural specificity. Dìdi’s identity as a first-generation Taiwanese-American facilitates a nuanced exploration of the familial dynamics that dictate so much of your lived experience at that age.

Being a teenager comes with a certain degree of solipsism. In a sea of angst and raging hormones, finding oneself is difficult. Every feeling is so intense, every experience all-encompassing. It’s easy to forget that the people who surround you, love you, and drive you crazy are, well, people too.

Chris Wang may forget that fact, but Dìdi never does. Amid his triumphant new experiences and mortifying faux pas, the film leaves space for other characters to express their own emotions. Every main character has a rich interior life and comes with their own dreams, regrets, aches, and inadequacies.

Dìdi attends to its characters' complicated emotions without ever becoming maudlin or, worse, saccharine. It is a film that feels honest, accurate, and grounded, with a few distinctive moments of absurdity to help set it apart from the crowd.

Giosué Greco’s original score makes the film float, with compositions that capture a sense of wonder and melancholy, even managing to express both simultaneously. Its unobtrusive simplicity effectively amplifies emotional beats throughout the film. At other times, Greco’s percussive pieces lend the film a propulsive excitement, be it rooted in zany exuberance or frenzied anxiety.

I loved Dìdi. I only wish it had lasted longer, a testament to the fact that the film doesn’t overstay its welcome. By its conclusion, Dìdi undergoes a satisfying arc of personal growth, but the film doesn’t force a tidy ending. Instead, it gently resists traditional narrative resolution because so much remains unresolved at fourteen. To suggest otherwise would be emotionally disingenuous, and Dìdi derives so much of its poignancy from its honesty.

While I cannot recommend Dìdi strongly enough, I will admit it was a bit odd to reflect on my own adolescence through the cinematic lens of retro nostalgia. It drove home the fact that I have matured more than I realize and that more time has passed than I care to acknowledge in my day-to-day.

Dìdi is perhaps the first film to make me feel old by reminding me what things were like when I was young. At twenty-six, aging has just begun to feel different. As I start to consider these feelings, I’m also acutely aware that I’m twenty-six. I can feel your more wisened eyes rolling at me right now. I understand it’s insufferable to listen to young people wax philosophical about “growing old.”

I’m young, but I used to be younger, and I won’t ever be as young again. Obviously, I’ve understood these basic facts of life for a long time, and still, I occasionally lament them. Time marches inexorably forward. I’m mostly at peace with that fact, and sometimes I yearn for the relative simplicity of whatever childish bullshit I was up to in August of 2008.

I can’t go back, but I can rewatch Dìdi, and that’s an incredible gift.

Until next week, find yourself a screening of Dìdi, my fellow film freak.

wait till you turn thirty spend the majority of your day interacting with Gen-z and soon Gen Alpha....My head simply screams "Shiiiiiiiit, I'm am definitely not a kid anymore" all day long now. It's cray cray out there. Loved the piece by the way, I'll have to give it a look.