“Most of the feckless, listless quality of today's art can be blamed on its drive to break out of a tradition while, irrationally, hewing to the square, boxed-in shape and gemlike inertia of an old, densely wrought European masterpiece.”

-Manny Farber in “White Elephant vs. Termite Art”

This week I had the opportunity to watch After Yang (2022), the sophomore feature film by South Korean director Kogonada. His debut film, Columbus (2017) is a humble masterwork that slipped under most people’s radar. Kogonada is one of the few directors whose creative vision I implicitly trust. I am eager to experience all his cinematic offerings, sight unseen.

After Yang, produced and distributed by A24, received a modicum of mainstream attention upon release. It is an entry into the sci-fi genre that is far more philosophical and contemplative than traditional fare. This is not a story of an alien invasion. There are no adventures into outer space. Instead, Kogonada constructs a vision of the future that is simultaneously familiar, rooted in modernist domestic spaces, and yet unlike anything I’ve seen before.

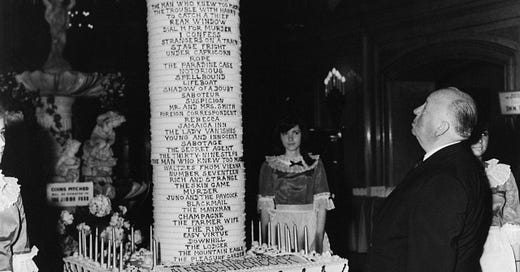

“Some films are slices of life, mine are slices of cake.”

-Alfred Hitchcock

Considering both of Kogonada’s films, do I prefer a slice of life or a slice of cake? Or, in the words of esteemed film critic Manny Farber, do I prefer the admirable “termite art” or the derided “white elephant?”

Call it a cop-out, but neither binary paradigm encapsulates the nuances of my personal taste.

I love cake, but the movies I hold dearest have deep resonance in my life and are, themselves, rooted in quotidian facets of existence, presented with a director’s signature style. So, to Mr. Hitchcock I say: I would like a slice of life, with frosting.

Mr. Farber’s distinction between “white elephant” and “termite” art is presented with derision for the “white elephant.”

Masterpiece art, reminiscent of the enameled tobacco humidors and wooden lawn ponies bought at white elephant auctions decades ago, has come to dominate the overpopulated arts of TV and movies. The three sins of white elephant art (1) frame the action with an all-over pattern, (2) install every event, character, situation in a frieze of continuities, and (3) treat every inch of the screen and film as a potential area for prizeworthy creativity.

-Manny Farber in “White Elephant vs. Termite Art”

Farber’s strong, subjective bias would be amended later in his career. “White elephant” and “termite” art are not, Farber realized, mutually exclusive categories. Though he may champion “termite art,” the “white elephant,” is not innately worthy of scorn.

As a result, his evaluative framework has become more fluid in its application. Yet it remains useful as I question why some “great” films stay with me for years while others pass by me like water off a duck’s back.

“Movies have always been suspiciously addicted to termite-art tendencies. Good work usually arises where the creators seem to have no ambitions towards gilt culture but are involved in a kind of squandering-beaverish endeavor that isn't anywhere or for anything.”

-Manny Farber in “White Elephant vs. Termite Art”

For example, Minari (2020), a film I think Farber would label “termite art,” is beautiful and intimate, and it almost never crosses my mind. Charlie Kaufman’s I’m Thinking of Ending Things (2020) exudes pretentiousness, so seduced by its own intellect that the resultant film is, at times, downright obtuse. It is a “white elephant,”, albeit mutated by Kaufman’s numerous idiosyncrasies, that I’m unlikely to revisit.

Then there are films like CODA (2021), a crowd-pleasing piece of cake and best picture winner, whose saccharine sensibilities hit my palette like a glob of grocery store frosting, sweet to the point of suffocation. Or the dreaded Green Book (2018), a smug white elephant whose reductive exploration of racial issues delighted the Academy and Baby Boomers all across America.

“The common denominator of these laborious ploys is, actually, the need of the director and writer to overfamiliarize the audience with the picture it's watching: to blow up every situation and character like an affable inner tube with recognizable details and smarmy compassion. Actually, this overfamiliarization serves to reconcile these supposed long-time enemies- academic and Madison Avenue art.”

-Manny Farber in “White Elephant vs. Termite Art”

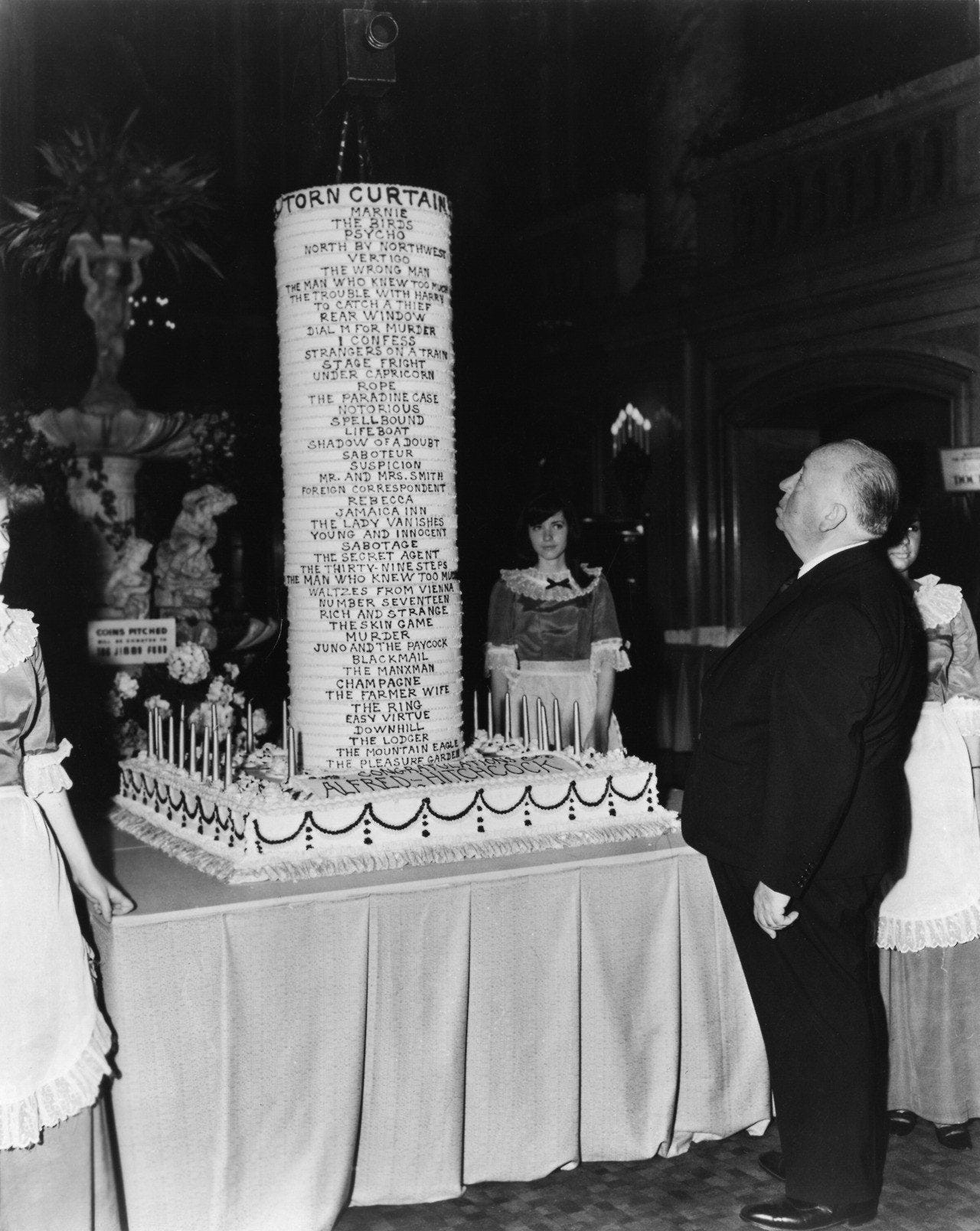

Studying film has created an irrevocable distance between film and myself as a spectator. Watching a movie was once an immersive narrative experience. Now I see each film as if it were light refracted through a prism. Sometimes I find myself fixated on a particular part of the refracted cinematic rainbow: be it the film’s use of color, cinematography, editing, dialogue, visual effects, narrative pacing, etc. For better or worse, this is how I’ve trained my brain to experience cinema.

It’s rare that the prismatic elements of cinema are able to recombine, somehow unrefracted, to shine a light on that which strikes me at my core. This elusive experience is the hallmark of something transcendent. Both of Kogonada’s films achieve this rare feat. I am not suggesting that makes Kogonada the greatest director of all time. Rather, his films are crafted in a way that speaks to my personal sensibilities as a cinephile.

I regard Kogonada’s first film, Columbus, as quintessential “termite art.” It ranks among my favorite films of all time. After Yang, by contrast, trends towards the “white elephant,” but still prominently features Kogonada’s treasured “termite” sensibilities.

Despite trending towards opposite ends of Farber’s framework, their shared attributes illuminate something about what makes me tick:

Both films have plots that meander meaningfully, unbound by Screenwriting 101’s strict adherence to Freytag’s triangle, and both films resist conventional romanticized resolutions.

Both films exist within a recognizable world, rendered anew through Kogonada’s lens.

Both films prominently feature a soothing score that enables the film to penetrate the ossified shell that encases my heart - developed as a result of academia and, perhaps, some degree of discomfort with displaying emotion related to masculinity.

Columbus (2017): Kogonada’s “Termite”

Currently streaming on Kanopy and Showtime.

Columbus, Indiana is a mecca of modernist architecture. Jin (John Cho) arrives in Columbus after his father, a famous architect, falls ill. He crosses paths with Casey (Hailey Lu Richardson), a townie that works at the library. She lives with and looks after her mother, and is enamored by her surroundings. As the son of an architect, Jin doesn’t share Casey’s love of Columbus, keen to leave as soon as he can. They cultivate a friendship, bonding over intimate discussions of ambition and obligation amid their meticulously designed surroundings.

Kogonada manages to articulate a metatextual awareness within the film, acknowledging that his languid style is not everyone’s cup of tea. Early in the film, Casey and her mother chat about their dilapidated car over dinner. It’s clear that vehicular maintenance fees are not in their budget. Casey’s mother takes a bite of the food that Casey prepared and says, “You think this could use a bit more spice?”

“I was going for something a little more subtle,” Casey replies.

“I don’t even know what that means,” her mother grumbles.

Casey elaborates, “You know, less obvious.”

“Why?” her mother asks, incredulous.

Casey’s response: “‘cause sometimes you can taste the food better, and there’s a better aftertaste.”

Her mother sets down her bowl, sips her drink, and lays on the couch. “You’re crazy,” she says.

There is no narrative justification for this exchange but I regard it among the movie’s most important scenes. As his debut film, Columbus functions as a sort of mission statement for Kogonada. While mother and daughter talk about seasoning their dinner, Kogonada is trying to speak to you, the viewer. He is aware that his film may register as “bland,” lacking Baz Lurhman’s dizzying pazazz a la Elvis (2022) or the caustic wit in Emerald Fennell’s Promising Young Woman (2020).

You can put down the film, just as Casey’s mother does with her dinner. You can dismiss the sentiment as crazy. Kogonada’s intent is not to admonish uninterested viewers. Rather, he desires transparency between his sensibilities as a director and those of his audience. His approach to filmmaking offers something else.

Kogonada elaborates on his non-judgmental stance towards audience engagement in the following scene, where Casey’s co-worker shares insights that he found scribbled in the margins of a book:

Koganda’s film asks if we’ve begun to lose interest in everyday life. Columbus seeks to rekindle that dwindling interest, not through empty displays of cinematic style but via extended dialogues about our surroundings, where we come from, and what we owe to those that raised us.

Columbus’ score, composed by Hammock, perfectly suits the film’s tone. As an anxious person, meditation is not a skill I am well-versed in. However, Columbus’ score combined with diegetic sounds of nature (the patter of rain or the chirping of birds) is, I think, as close to zen as I’ve ever gotten.

On one of their first walks together, Casey takes Jin to see the town’s bank. Jin asks if Casey likes the building. She does. She explains that this building is one of the first modernist banks in America, its glass walls giving the space an openness, whereas most other banks would be imposing structures with tellers behind bars.

Kogonada’s camera shoots Casey within the window’s reflection. Her face is blurred by the window reflecting the exterior of the bank. As Casey recites facts about the all-glass bank we are unable to see the building’s interior.

Jin interrupts Casey. “Stop with the tour guide mode of a second,” he says, “You said this is one of your favorite buildings. Why?”

A wide shot shows Casey’s back as she looks into the bank, its interior still obscured. Casey shrugs and repeats, “It’s one of the first modernist banks in the United States.”

“No, no that can’t be it,” Jin says, “Do you like this building intellectually, because of all the facts?”

“No,” Casey replies, “I’m also moved by it.”

“Yes, tell me about that. What moves you? I’m interested in what moves you…”

The film cuts to a close-up of Casey, the camera positioned inside the bank, looking through the window. Casey begins speaking, but her words are inaudible through the invisible barrier. Our view of Casey is no longer a reflection, but Koganda preserves the intimacy of the moment by denying us Casey’s answer.

The film’s score slowly fades in, “Eliel” by Hammock, which I’ve included below. If you can, pop in headphones and give it a listen. It conveys emotion without words and offers a small taste of how Columbus feels:

Kogonada allows us to have our cake and eat it too as we witness Casey render herself vulnerable while Kogonada withholds the particulars of her vulnerability. Her words are for Jin, but her experience opening up to Jin is ours to observe.

This was the moment I fell in love with Columbus. I remain enamored to this day.

…termite art aims at buglike immersion in a small area without point or aim, and, overall, concentration on nailing down one moment without glamorizing it, but forgetting this accomplishment all as soon as it has been passed; the feeling that is expendable, that it can be chopped up and flung down in a different arrangement without ruin.

-Manny Farber in “White Elephant vs. Termite Art”

After Yang (2022): Kogonada’s “White Elephant”

Currently available for rental or purchase on V.O.D platforms.

In a distant but recognizable future, Yang is an A.I. techno-sapien that Jake (Colin Farrell) and Kyra (Jodie Turner-Smith) have purchased as a companion for their adopted daughter, Mika. He was initially acquired as a way for Mika to remain connected to her Chinese ancestry and culture. Over time, Yang becomes a fixture in Mika’s life and is, essentially, part of the family. When Yang malfunctions, Jake scrambles to find a way to fix their beloved A.I. whilst the family grapples with the specter of loss, grief, and a bounty of meaningful memories. Despite the prominence of A.I. in After Yang, the film exudes humanity.

After Yang is a beautiful and complex film. As its narrative progresses, the movie’s meaning seems to evolve and change. It is a film about family, data privacy, what makes us human, the challenges of finding proper medical care and so, so much more.

As I glided through the cosmic landscape of Yang’s memory, I found myself deeply moved by snippets of the memories that Yang deemed valuable. If I were to view this sequence on mute and devoid of context, the montage of memories would likely register as a mundane and confusing series of unrelated images. However, immersed in the cinematic experience its meaning was immense, unleashing a deluge of emotion.

Once more, Kogonada presents a metatextual reflection of his film’s intention, this time in a flashback conversation about the mysterious nature of tea. Jake and Yang’s discussion of tea articulates the occasionally overwhelming complexity of After Yang’s cinematic ambitions.

I recommend Kogonada’s work without hesitation. Columbus is everything I could ever want from “high-brow” art. In After Yang, “I’m not sure if I can taste the forest… maybe I haven’t the language for it.” Perhaps I will discover the words upon rewatching the film, which I suspect I will do many times.

Thanks for your attention. See you next week, my fellow film freak.

Or, if there are other film freaks that you know, please: