The Road to the Beginning of the End of the Road

A review of Fast X (2023).

Vrooming, Zooming, and Booming

Fast X, the eleventh film in the “Fast Saga” rolled into theaters this weekend, sporting an oxymoronic tagline that suits the moronic saga well. I employ “moronic” in a purely descriptive sense, stripped of any pejorative connotation. I think that The Fast Saga’s most ardent fans would agree. These films are, among many other things, quite stupid and Fast X is no exception.

I caught an IMAX screening on a Friday afternoon, while the kids were still at school -- not my kids. I don’t have children, I just try to avoid them - especially at movie theaters. It was a temperate spring day. Before my screening, I spent some time in the park with my bud, Jack Herer. I made it to my seat before the trailers (a very rare occurrence for me) and had ample time to settle myself, clean my glasses, and prepare my notebook and pen.

Yeah, I took notes during Fast X. Why shouldn’t The Fast Saga films deserve the same level of critical analysis as highbrow award-bait cinema that critics croon over? Empty-headed though it may be, The Fast Saga strikes me as an incredibly fascinating piece of commercial cinema.

To ask, “Is Fast X good?” is to ask the wrong question. Fast X is the eleventh Fast and Furious film. I liked it more than 8 and 9, but ultimately it’s just more of the same. It’s another installment in Hollywood’s most profitable hyper-masculine cinematic telenovela that has spanned two decades, earned over 6.5 billion dollars worldwide, and escalated to absurd heights.

F9’s biggest problem was its self-awareness. It harped on its own idiocy by “lampshading” its implausibility. Lampshading is a technique used in screenwriting to smooth over a film’s glaring issues, oftentimes through self-awareness. Pointing to the problem diffuses the threat to viewers' “willing suspension of disbelief” without actually fixing the issue.

F9 wants you to know it’s smart enough to know it’s stupid. Its attempts at cheekiness are grating. F9 is not Ibsen. I’m fine with that, but F9 was embarrassed enough to conspicuously lampshade its silliness. Thankfully, Fast X has no such reservations. It’s a big, loud, and unrepentantly stupid celebration of the entire Fast Saga and all its brainless bombast.

The real question is, “Is The Fast Saga worth watching?” Fuck if I know. Are they meaningful films? Absolutely not. Am I glad I’ve watched them? You better believe it.

Will you enjoy them? Does a ridiculous, hypermasculine cinematic telenovela sound appealing? Therein lies your answer.

The Road to the Beginning of the End of the Road

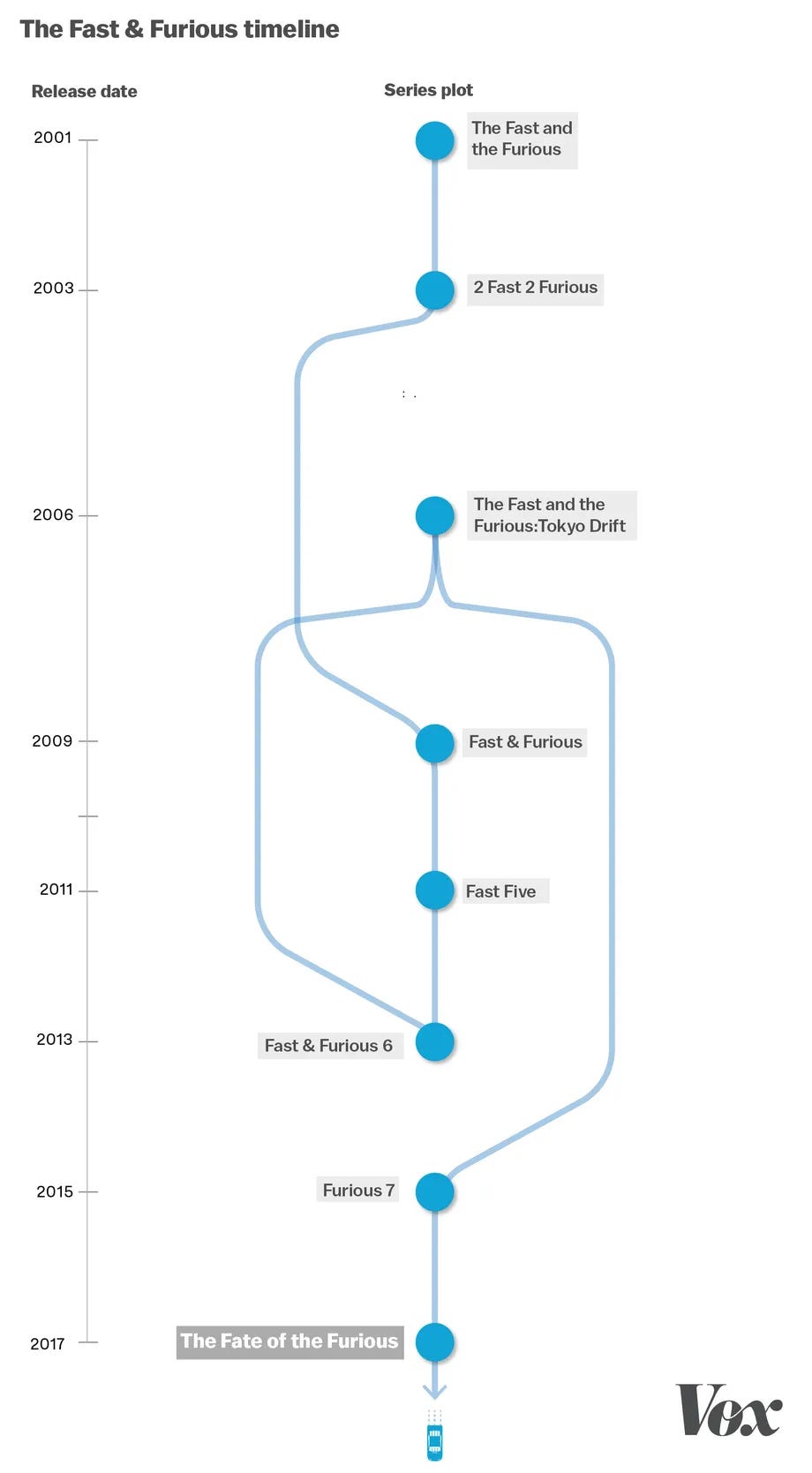

The road to Fast X is long and winding. It veers in unexpected directions, oftentimes doubling back to revise, retcon, and retrofit its way toward some semblance of narrative continuity for the franchise as a whole. As the Fast Saga clumsily retrofits its own story, audiences are rerouted into precariously contrived loop-de-loops of soap-opera shenanigans. That is because, at its core, The Fast Saga is nothing more than a masculine-coded telenovela. Characters that you’ve seen die are rarely ever dead. Secret sons, brothers, and bouts of amnesia are some of the narrative devices employed to keep the franchise chugging along. So, as you can imagine, the narrative continuity of these films is positively fucked. That’s part of The Fast Saga’s charm.

It all started with The Fast and the Furious (2001), a rip-off of Point Break (1991) with more cars and less charisma. LA P.D. Officer Brian O’Conner (Paul Walker) goes undercover, infiltrating the world of underground street racing in search of a crime syndicate known for hijacking electronics from cargo trucks in modified Honda Civic Coupes. He embeds himself with Dominic Toretto’s (Vin Diesel) crew and falls in love with Dom’s sister, Mia (Jordana Brewster). Upon discovering Dom & friends are the criminals he is looking for, Brian’s loyalty to the law clashes with the bonds he’s formed with his bros and his love for Dom’s sister, Mia.

If you’ve seen Point Break you can figure the rest out. If you haven’t, I’d recommend watching Point Break over The Fast and the Furious because, to be honest, The Fast and the Furious isn’t an interesting movie. Its sole contribution to an otherwise familiar action formula is automotive fetishism. Motorheads and car enthusiasts may find that sufficiently alluring, but I am not one of them.

I know absolutely nothing about cars and I doubt I’ll ever put in the effort to learn about them. They simply don’t spark my curiosity or imagination. I’ve never fantasized about driving a specific car. I don’t fetishize cars. I don’t plan on owning one, but if I did its function would be purely utilitarian. So, as a film, The Fast and the Furious doesn’t have a particularly strong personal appeal.

I, on the other hand, much prefer Point Break and all its homoerotic subtext. There are transcendent moments, like when John C. McGinley says to a young Keanu Reeves:

That’s poetry. I mean, how can you top that?

My point is that there’s nothing particularly appealing about The Fast and the Furious unless you’re obsessed with cars. It’s a film about family, loyalty, and stolen Panasonic TV/DVD players. It’s small potatoes.

As a standalone film, it’s entirely unremarkable. As a part of the “Fast Saga,” it’s conspicuously underwhelming, which isn’t necessarily a criticism of The Fast and the Furious. Rather, it’s a commentary on a franchise composed of disjointed films that have been crudely slammed together. It’s about where the Fast Saga goes (i.e. balls-to-the-wall berserk) and how it gets there. As the franchise progresses, our Panasonic TV bandits engage in a series of escalating escapades that include hauling bank vaults through the streets of Rio de Janeiro, preventing nuclear war, and driving a car into outer space.

There seems to be a consensus that Fast Five and Furious 7 are the best of the series. Fast Five is where the franchise hit its stride, and as a heist movie, feels identifiably different from the others. Paul Walker died while Furious 7 was filming, which lends the film a metatextual pathos that the rest of The Fast Saga does not, and cannot, ever offer.

That’s because the rest of The Fast Saga movies are individually indistinct and collectively incoherent. There’s nothing particularly interesting about a single Fast Saga film. Their magic lies in the way they don’t fit together but are, nevertheless, forced to connect.

Much like a telenovela, The Fast Saga should’ve ended years ago. Like TV soap operas, some episodes are more memorable than others. If you’re invested, you’re in it for the long haul. In that way, much like an automobile, The Fast Saga is greater than the sum of its parts.

Vroom Vroom!

Subscribe to Acquired Tastes for a newsletter delivered to your inbox every Sunday:

Beep Beep!

Sharing this post with film freaks you know will help Acquired Tastes grow, so tell your homies to roll up:

Skrrt Skrrt!

See you next week, my fellow film freak.

I'll be sure to skip this installment, as I have the rest. But the comparison to Point Break is fun.