The Strange Pleasures of "Trojan Horse Genre Franchises"

and Final Destination's Six Dances With Death.

Soapy Shenanigans in The Fast Saga & The Book of Saw

One of the delightful parts of being in my twenties is watching the popular film franchises that dominated the box office and the pop-cultural zeitgeist, but I never bothered to watch for some reason or another.

Sometimes, it was because of simple disinterest (as was the case with the Fast & Furious franchise). Other times, it was because I was too young (as was the case with the Saw franchise). Years later, with my mind pried open by the rigors of film studies, it’s fascinating to watch franchise films and see them for what they truly are.

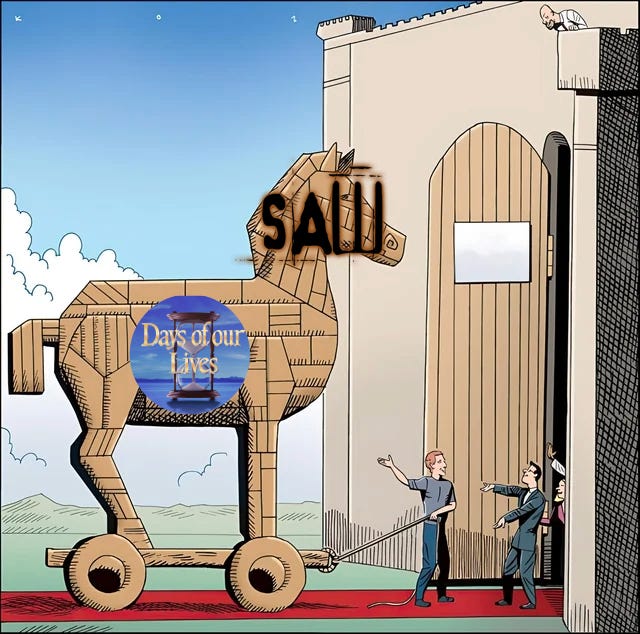

I’ve never been a fan of soap opera shenanigans. When I think about Days of Our Lives, for example, I see a mode of storytelling that relies on comically contrived tropes to sustain a serialized narrative that’s never supposed to end. It keeps going because people keep watching, which makes the network money, and so it must never end. Writers spin their wheels as the show shambles forward, but it’s a creative endeavor running on fumes.

I’ve never actually watched a soap opera, but they’ve been on in the background enough for me to know I’m not interested. Honestly, I harbor a vague resentment towards soap operas, rooted in some philosophical objection to the artistry of narrative storytelling being bastardized by the financial incentives that drive the creative endeavor.1 Financially viable but artistically bankrupt narratives? “Yuck!” past-Skylar declared, “That slop’s not for me. I would never!”

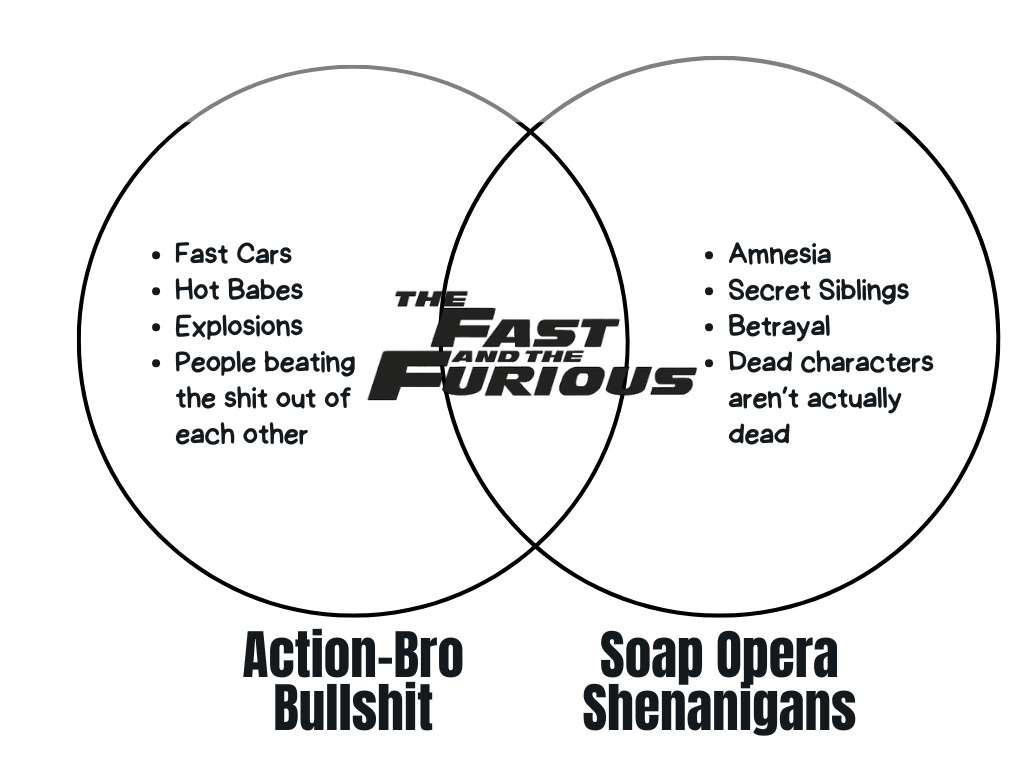

With 27 years of wisdom, eleven Fast & Furious movies, and ten Saw movies under my belt, now I can see the truth. Both Saw and Fast & Furious exhibit the narrative sensibilities of daytime soap operas cloaked by the aesthetic conventions of their respective genres.

I still am not attracted to hot cars or busty babes, nor do I find grotesque torture aesthetically interesting or challenging, yet when those elements become the aesthetic trappings draped over the skeleton of a soap opera— replete with bouts of amnesia, secret siblings, flashbacks that “change everything,” and characters that die but never stay dead —it hits the palate in a completely different way. The bland soap-opera bullshit that fuels As the World Turns is much zestier in dissonant narrative contexts.

So, when Lenny Ortiz appears in Fast & Furious 6 as an antagonist with amnesia despite having been killed off in the fourth film, I live for that dumb shit. I love it because it’s dumb, and I don’t give a fuck that it’s bad storytelling perpetuated by profit. The delicious irony of finding that particular strain of narrative slop (i.e., daytime soap-opera shenanigans) at the center of The Fast Saga more than compensates for the unsavory, soapy flavor notes.

Unsavoriness remains prominent in the Book of Saw, but the temporal fuckery that unfolds within countless flashback sequences across eleven films induces a severe narrative whiplash. Although extremely disorienting, the residual feelings of bemused confusion help spice up the numbing, one-note premise that Saw repeatedly trots out because it continues to sell. I would regard The Book of Saw with the same disdain I afford The Young and the Restless had Saw X not blown my mind with a half-decent story.

That’s another noteworthy quirk of these Trojan Horse franchises: it takes them numerous attempts to produce something that resembles a compelling product.

There’s a general consensus that Fast Five is a good movie, arguably the best of the series.2 I would recommend it, but its four predecessors are fucking duds, and every film which follows is stupid as fuck. Yet they flop in a more spectacular fashion than the early sequels, which is a source of their enduring appeal.

The charm of a Trojan Horse Genre Franchise lies in the chasm between the franchise’s marketable image, rendered through genre and tailored towards specific demographics, and the actual film itself, which, in the case of The Fast Saga and The Book of Saw, are telenovelas in disguise.3

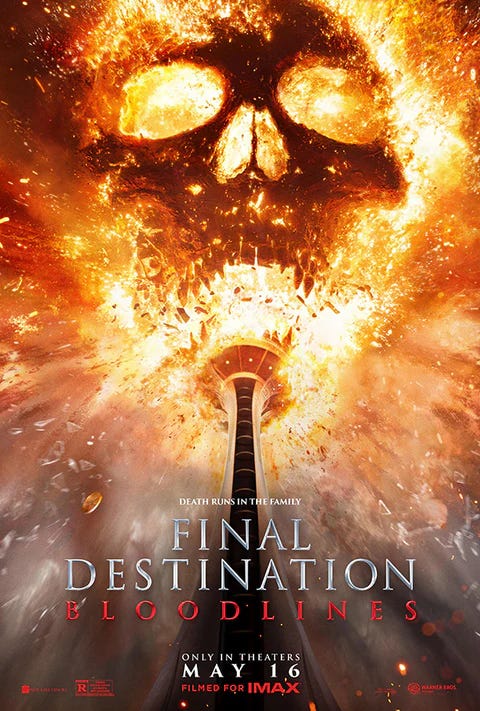

The Final Destination Franchise, with its sixth installment now in theaters, isn’t the same breed of Trojan horse. Rather than being secretly soapy, Final Destination films are actually feature-length episodes of Disney’s That’s So Raven crossbred with SpikeTV’s 1000 Ways to Die. It shouldn’t work, and most of the time it doesn’t, and yet a quarter century after the franchise began, along comes Final Destination: Bloodlines.

So, this week, I watched all five Final Destination movies so that I could see the sixth and report back to you with my findings. I know, nobody asked me to. That’s what makes my sacrifice so heroic, and those are your words, not mine.4

Death Has a Plan, Final Destination Has a Formula

Here’s how every Final Destination movie works, using the original film as an example:5

Our protagonist interprets a series of unrelated occurrences as warnings of looming disaster. These signs include:

The removal of a luggage label from a suitcase.6

Rolling over in the middle of the night, the digital clock flickers between 1:00 am and 180, the upcoming flight number for the class trip to Paris.

Being told, “Death is not the end,” by a Hare Krishna handing out pamphlets at the airport.

The flight departs at 9:25 pm, and the protagonist's birthday is September 25th (9/25).

While pooping, “Rocky Mountain High” by John Denver plays over the airport speakers. “I’ve seen it rain fire from the sky,” the singer, killed in a plane crash, croons.

Our protagonist is seated in row 25.

This is called apophenia: “the perception of patterns or connections between unrelated or random data, objects, and ideas in situations where no such patterns actually exist.” Typically the basis of benign superstition, “extreme forms… can have wide-ranging impacts on human cognition and behavior—contributing, for example, to delusions and being symptomatic of mental illnesses such as paranoia and schizophrenia.”7

The Final Destination franchise repeatedly affirms the validity of these apophenic delusions, which makes the film’s narrative logic feel, for lack of a better term, schizophrenic, which adds to their charm.

Our protagonist doesn’t heed the apophenic warnings and proceeds despite their gut feelings. A series of occurrences ensue that, once again, establish a pattern that precipitates the impending accident.

Two hot girls ask to switch seats with our protagonist.

The tray table at our protagonist’s new seat is broken.

A classmate boards the plane late.

Our protagonist doesn’t heed the signs, and a fatal accident ensues. These front-loaded sequences feature spectacular carnage unmatched by anything that follows.

In the original film, it is a fiery plane crash that screams, “9/11 hasn’t happened yet.”

Subsequent fatal spectacles include: an explosive series of car accidents on a freeway, a deadly rollercoaster malfunction, a crash at a racetrack, and a bridge collapse.

Our protagonist reverts to before the fatal disaster, which was actually a premonition that’s so Raven. They recognize the pre-disaster pattern of events described in #2.

Realizing they’ve seen the future, the protagonist flips out. Their histrionics get the attention of a handful of supporting characters that, for some reason or another, cause them also to avoid their doom despite continuing to doubt our raving protagonist.

While our supporting characters try to quell our panicking protagonist, the fatal disaster occurs and proves the protagonist was correct.

Days or weeks later, one or two survivors die elaborate deaths that draw the protagonist’s attention.

The protagonist realizes that the survivors are dying in the same order in which they perished in the premonition.

The protagonist, supported by a single secondary character, tries to warn the remaining survivors. The remaining survivors don’t believe the protagonist’s warnings because they sound fucking insane.8

Our protagonist will often continue having vague premonitions of how the next victim will die and attempt to intervene to no avail,9 which is also soooo Raven.

When only a few survivors remain, our protagonist finds a way to cheat Death via some loophole (e.g., if you save the person slated to die next, Death skips over them).

Against all odds, 2-3 characters survive.

Time jumps forward, and our survivors are reunited. Not one to be trifled with, another accident ensues, killing everyone, because Death cannot be stopped, only delayed.

End credits roll, leaving you to contemplate the inevitability of death and the futility of everything that transpired in the movie you’ve just watched.

It’s always the same formula, and there’s no attempt to create a serialized narrative10 that typifies soap opera storytelling. Instead, each episode stands alone, more like a sitcom, with only passing references to previous films that, at most, constitute the soft serialization standard of sitcoms.

Like The Book of Saw, the incongruous narrative structure of the Final Destination movies (i.e., that of feature-length, macabre episodes of That’s So Raven) was bonkers enough to sustain my engagement with an otherwise lackluster franchise.

Death has an M.O. Until It Doesn’t

The first three films are standard fare for early-2000s horror. Style is absent, shot with flat angles against an uninspired mise-en-scène that further evokes the aesthetics of a Disney sitcom. The lore remains static, so there’s only minor variation across the original trilogy. However, with each sequel, Death becomes more elaborate. By Final Destination 3, Death has a name, and it’s Rube Goldberg. When you’re essentially watching the same movie thrice, the more outlandish they get, the better.

By the end of the third movie, Death has an established modus operandi:

Death has no physical form but travels on a breeze. If it’s windy in a Final Destination movie, Death is up to his tricks.

Death’s domain is exclusively external. Characters can prolong their lives by baby-proofing their environment or living in a padded cell. When these precautions are taken, Death is vexed. It can facilitate elaborate accidents with multiple components but cannot, for example, influence your platelet count to induce a blood clot. Hematology and all other internal medicine are beyond Death’s grasp.

Death likes to tinker, often relying on loose screws and flawed engineering to do its dirty work. It also enjoys mixing electrical mechanics with water and playing with highly flammable substances.

The Final Destination, the quizzically titled fourth installment of the franchise, came along in 200911 and takes the franchise to the pits. It is the era of useless 3-D blockbusters, and, ironically, our cast is more one-dimensional than they’ve ever been. Along with the most unlikable group of “characters” the series offers, Death gets far more hands-on, leaving behind the deadly game of Rube Goldberg dominoes for direct intervention.

Take, for example, the death of The Racist, whose virulent hatred compels him to drive to a black character’s house to erect a burning cross in their front yard. It’s an ugly and hateful scene, and obviously, he gets what’s coming to him. However, Death behaves more like The Invisible Man than Death as established in Final Destination 1-3.

It begins with Death arriving on its characteristic breeze, dislodging a trinket hanging from The Racist’s rearview mirror, which turns on the radio. Then, to facilitate a cheeky demise of the wannabe Klansman, Death locks the doors, shifts the car into gear, and opens the gas tank. (???)

Death doesn’t claim the character; it directly kills the character. The difference may seem insignificant, but it is part of a larger divergence from the style and sensibilities of previous films. The Final Destination (4) is the Scream 3 of the Final Destination franchise - a horror movie that, at its core, is more interested in comedic sensibilities.

The entire thing plays like a bad joke; hence, The Racist is dragged through the street ablaze as “Why Can’t We Be Friends?” by War plays from the truck’s radio. It’s deeply unserious but never manages to amuse. It’s more self-aware, more misanthropic, more cynical, and far less tolerable. Despite being the shortest film in the series, it was a very long 82 minutes, with enough “endings” to rival Return of the King.

Thankfully, Final Destination 5 is a return to form for the franchise. Death is more hands-off, the cast has some semblance of chemistry, and there’s an addition to the lore for the first time: you can get off Death’s list by killing someone else, thereby stealing whatever time they had left. This introduces a moral quandary to Final Destination’s stale formula that, unfortunately, the fifth film doesn’t manage to utilize in interesting ways.

Final Destination 5 is a fine movie, but if you consider it within the framework of The Final Destination franchise, it’s stellar. Is that damning with faint praise, sure, but the series seems to be moving in a more promising direction, which brings us to the latest, and hopefully final, Final Destination movie.

Bloodlines’ Success Highlights Previous Failures

Like Fast Five or Saw X, Final Destination: Bloodlines is where the series finally hits its stride. Is it too little, too late? Almost certainly. Yet the fact remains, Final Destination: Bloodlines is the best entry in the franchise by far. By now, it should be evident that I’m evaluating Final Destination movies on a curve, but Final Destination: Bloodlines is a curve breaker.

Imagine my surprise when I found myself not only tolerating the characters but actually liking them. Final Destination only needed six attempts to understand that characters are essential to half-decent storytelling.

In lieu of actual characters, previous installments provided archetypes that vaguely evoked the shape of characters. The Final Destination (4) is particularly egregious in this regard. It has the flattest archetypes and operates on the erroneous assumption that unlikeable archetypes are more fun to watch die in strange and elaborate ways.

In reality, seeing The Misogynist get his intestines sucked out of his butthole at the bottom of a draining pool is no more satisfying or interesting than watching Underage “Hot Girl” #1 and Underage “Hot Girl” #2 get roasted with their tig ol’ bitties out in Final Destination 3’s tanning bed sequence.

Yes, The Misogynist is less likable than the generic, hyper-sexualized high school girls; their crime was that they were women. Even worse, they were attractive women with large breasts, and Final Destination 3 goes out of its way to try and convince me that these two naked (canonically underage) hotties are vain (because they are hot and care about their appearance enough to go tanning) and bitchy (because they don’t want to fuck any of the creepy guys whose entire personality is trying to get laid).

Obviously, I’m not buying that bullshit, but the movie makes sure that I don’t sympathize with those women. That way, I can “enjoy” their creative demise without being troubled by my pesky moral conscience or insidious empathy, both of which Final Destination 3 thinks stand to ruin my moviegoing experience.

“We can’t let the consumer get too close to the meat we’re serving them,” the movie thinks. So it stands to reason that the more unlikeable the characters, the more satisfying their demise, right?

If that were the case, then the death of The Racist (sporting a reprehensible hard-R) in The Final Destination (4) would’ve been the pinnacle of all that Final Destination stands to offer viewers, but it isn’t. It’s just more of the same, which, by movie four, is wearing painfully thin.

Listen, I haven’t a tear to shed for The Racist that gets lit on fire and smeared across asphalt by his own truck. Absolutely no love lost there. But nor do I mourn the loss of Gymnast Intern in Final Destination 5 or the Mom who gets decapitated by the elevator in Final Destination 2, etc., etc.

I don’t feel anything when anyone dies in these movies because none of the characters even come close to being complex, interesting, or relatable. They’re fodder for the novel deaths that heretofore constituted Final Destination’s only source of appeal.

Final Destination: Bloodlines’ primary innovation to the series formula is — and bear with me, because this is a radical concept— what if the characters were likable?

Nothing too crazy, just a cast of actors with a rudimentary grasp of conversational chemistry. Maybe they’re a family with pre-existing relationships that facilitate amusing rapport.

Oh, and what if the characters like each other enough to try and save each other, not because they’re concerned that they’re next on Death’s call-sheet, but because they genuinely don’t want to watch their brother die. Most of us would prefer not to watch our family members die horrific deaths, so that could be a relatable premise, right?

This facilitates Final Destination: Bloodlines’ revelatory paradigm shift: what if the viewers liked the characters enough not to wish violent deaths upon them? It’s a concept that Final Destination 5 flirted with, but never managed to nail. Bloodlines nails it and takes it a step further: what if the viewer preferred that the characters not die?

When you buy a ticket to Final Destination, you’re paying to watch elaborate death sequences. With violent demise guaranteed, what if the inevitability of the characters' deaths conflicted with my desire to see them succeed? Then things become complicated, more interesting, and it only took Final Destination six tries over a quarter century to crack the code to Storytelling 101.

Watching likable characters try to outsmart Death makes for higher stakes because, for the first time, I marginally care who lives and dies. In fact, I’d go so far as to say I’d prefer that Bloodline’s characters didn’t die. So I get emotionally invested in their attempts to thwart Death’s grand design, which Bloodlines cautions against lest things “get messy.”

Suddenly, I feel something no Final Destination has ever stirred within me. Is it— could it be… tension? Why yes, it is! And what’s that there? Oh, it’s a scrap of pathos! What a welcome addition to the Final Destination formula!

Eventually, I get what I paid for. Death comes to collect, but for the first time, I feel some emotional conflict. When the characters meet their grisly ends, and they will, they’re more than just dismembered sacks of meat. Splattered innards become more than a gruesome spectacle. Instead, the bloodshed is like spilled milk: nothing to cry over, but a genuinely lamentable mess.

Final Destination: Bloodlines deserves special commendation for evoking such a comparatively strong emotional response from me. It is far and away the best Final Destination film, and yet the relative simplicity of Bloodlines’ crowning achievement is functionally an indictment of the rest of the series.

Bloodlines does a good job of tying together every installment, offering unexpected narrative closure. So please, no more Final Destination movies. Go out on a high note. Quit while you’re ahead, I beg of you.

Alas, I fear the continuation of this IP is as inevitable as death and taxes.

Thank you for reading Acquired Tastes, Film Freak!

Until next time, stay alert. Death is everywhere.

This is, of course, not exclusive to soap operas. In fact, it’s a gripe I have with televisual storytelling. Good stories need a beginning, middle, and end for their characters. If a show starts without a planned conclusion, it will almost always continue until it runs itself into the ground, which is a shame to watch.

Plenty of fans champion Furious 7, but I maintain that the emotional resonance that carries that film is reliant upon the extratextual death of Paul Walker during filming. It undeniably impacts the film by ratcheting up emotions, yet I would contend that extratextual grief doesn’t change Furious 7 into a materially better film.

Like sheep in wolves’ clothing! ¡Scandaloso!

If you believe this description of me as “heroic” has been misattributed to you, please submit, in writing, a letter of objection and mail your complaint to the offices of Acquired Tastes (address not provided).

In your letter, please be sure to identify yourself, explain in-depth why you think I’m not heroic, and enclose a check for $250. Upon receipt, we’ll be able to correct our error.

Until then, we thank you for continuing to extol Skylar’s heroism— your words, not his.

Spoiler alert, if you care.

ALEX: Whoa! Whoa! Mom, you gotta leave that on. It's like... the tag made the last flight without crashin' or anything, right? So, it should stay on, or with, the bag for good luck.

BARBARA (his mother): Where would you get a nutball idea like that?

Source: https://www.britannica.com/topic/apophenia

My favorite example is in Final Destination 3, when Lady Protagonist (Mary-Elizabeth Winstead) uses printed photos to try and explain what’s happening to Supportive Male Friend (Ryan Merriman) like this:

One of the three pieces of evidence provided is a photograph of Abraham Lincoln, whose tenuous connection is explained by Lady Protagonist. Then comes a photograph of a plane’s shadow cast on the World Trade Center.

“Well, what do these pictures have to do with us?”

His question is not answered. The explicit but inexplicable reference to 9/11 is so goddamn unhinged I have no choice but to respect it.

My personal favorite is in Final Destination 2, when Lady Protagonist (A.J. Cook) is speaking with Supportive Police Officer (Michael Landes) and suddenly screams, “PIGEONS!” They race to the next victim’s location, outside a high-rise building, and attempt to warn them by screaming, “THE PIGEONS!” from afar, and then this happens.

Until Bloodlines, that is.

A terrible year for contemporary mainstream horror cinema.

What a treat to laugh because of the way you write and the words you choose, to then laugh at horror.

I noticed in the film clip of the racist, the truck had the word destiny on the back of it. You’ve taught me to notice the not so obvious.