A Cryptic Killer Chiller

As I have matured, my nightmares have become more mundane. Loved ones have replaced masked killers, and my distress is rooted in grief, unpreparedness, or social ostracization. My subconscious lacks creativity, and my night terrors have become pedestrian. Luckily, movies like Longlegs crawl out of disturbed, creative psyches to remind me of the omnipresent dread of my youth. It’s an immersive cinematic nightmare that feels like nails on a chalkboard, engineered to make your skin crawl.

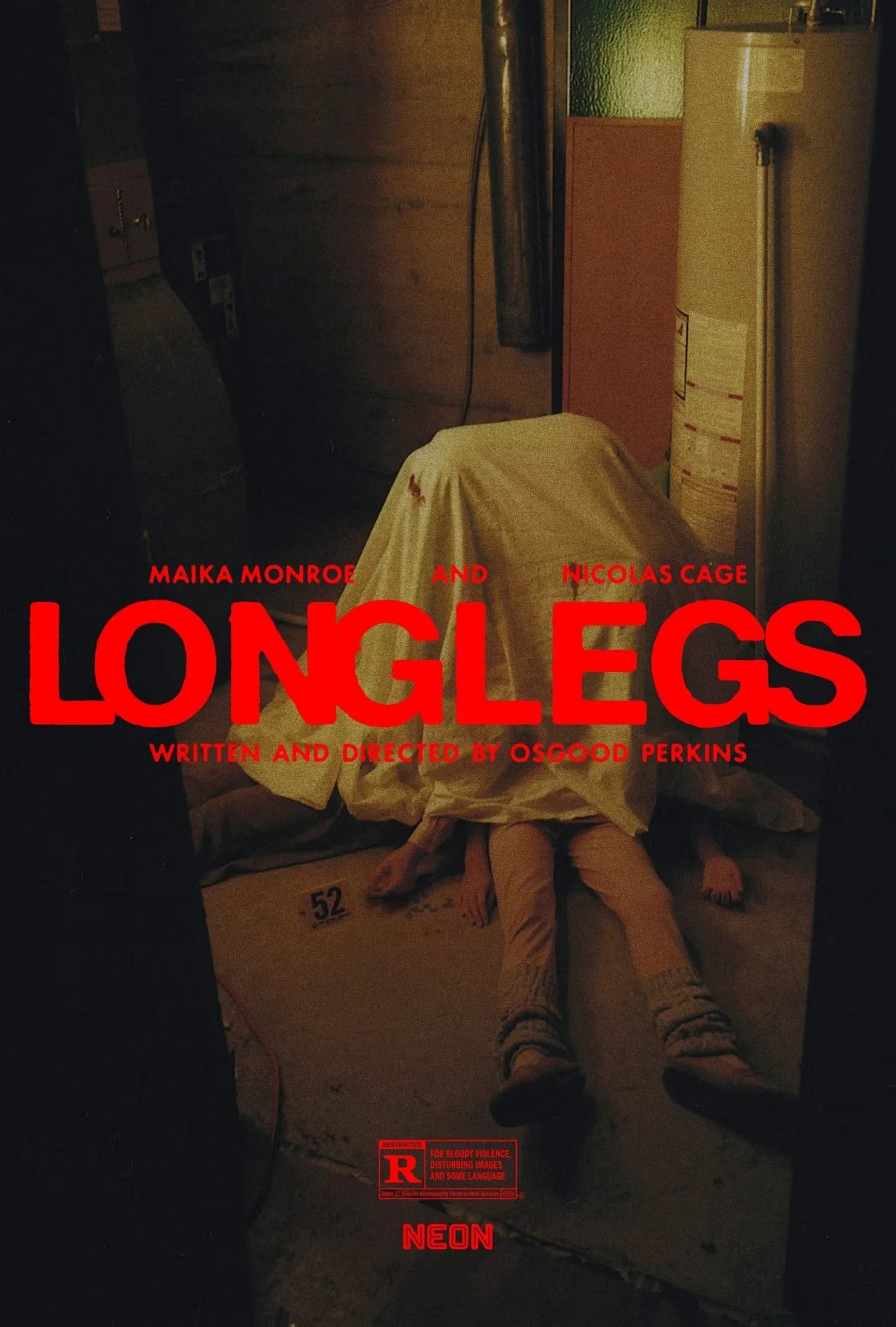

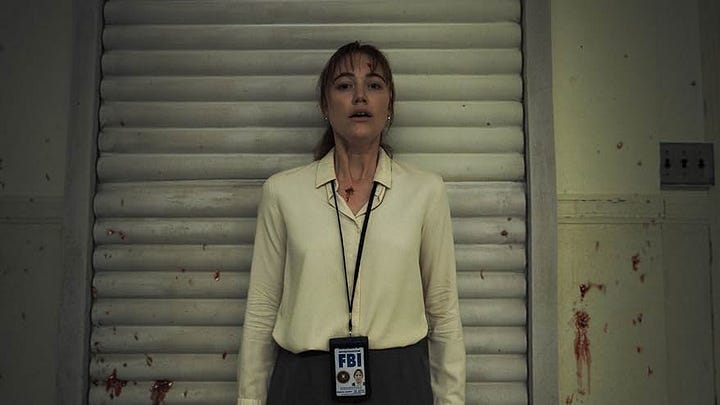

Written and directed by Osgood Perkins, Longlegs follows Lee Harker (Maika Monroe), an FBI agent working to catch the titular serial killer (Nicolas Cage). Fresh from Quantico, Agent Harker evokes Clarice (Jodi Foster) from Silence of the Lambs (1991). Her investigative instincts are preternatural, like Patricia Arquette in an exceptionally fucked-up episode of Medium.

Monroe offsets the outlandish facets of her character with a grounded performance as the neurodivergent savant: awkward, endearing, likely on the spectrum but never the subject of mockery.

Monroe’s restraint allows Nicolas Cage the space to indulge his more esoteric impulses. Between (mostly) convincing prosthetics and disquieting vocal modulation, there are moments where Cage disappears into the role. However, in his most explosive moments, it’s impossible not to see Nic Cage doing what he does best: freaking the fuck out. However, even when Cage’s persona is at its most obtrusive, Longlegs proves capable of sustaining Cage’s singular brand of unbridled mania.

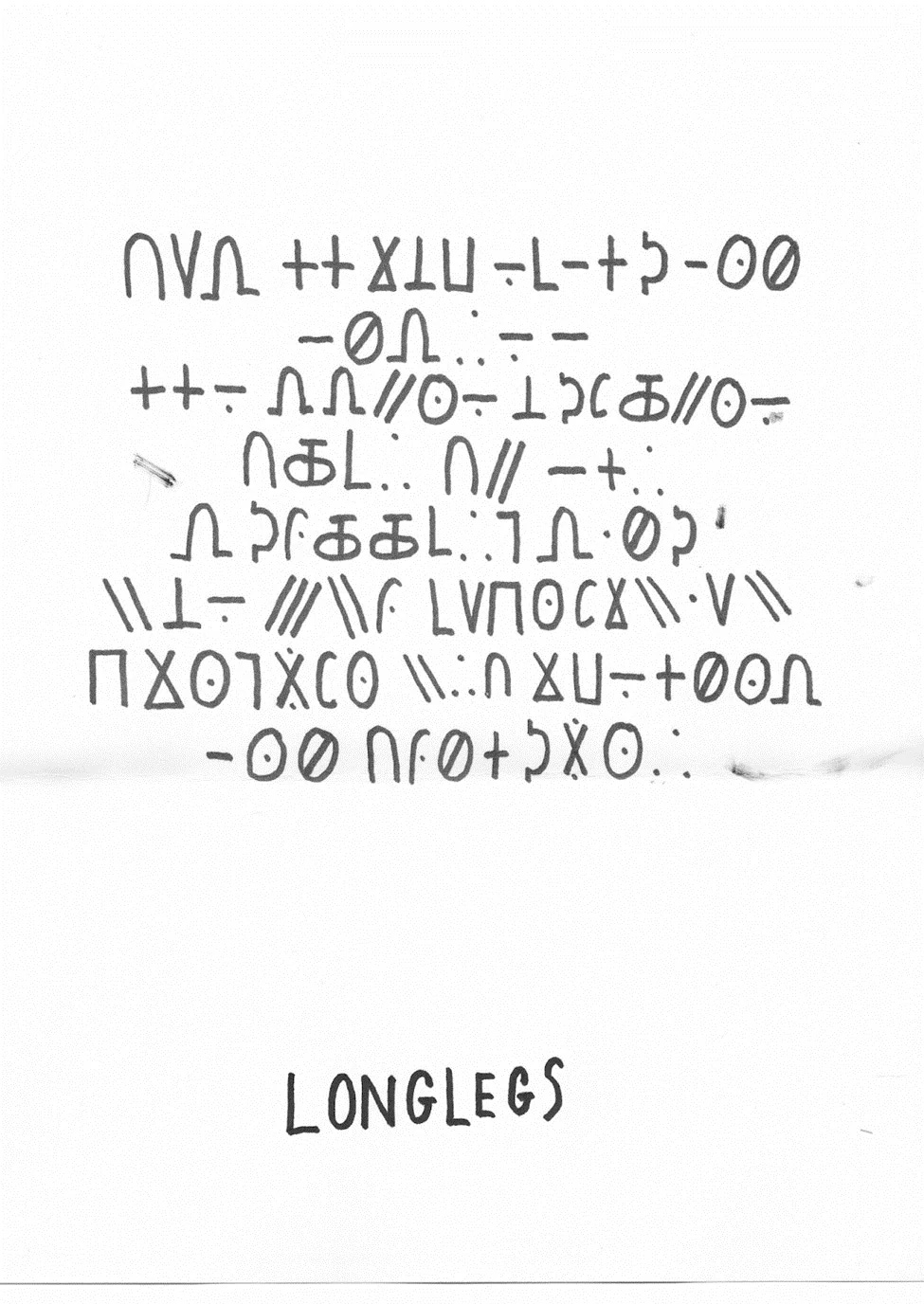

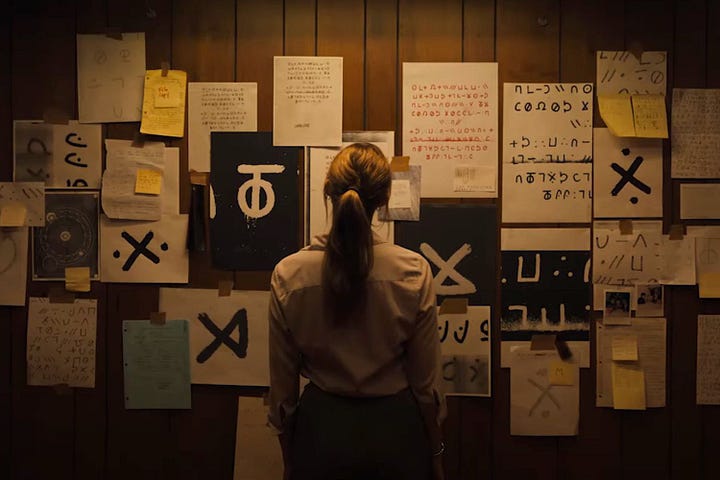

You see, Longlegs is no ordinary murderer; his crimes span decades, and his methodology is obscure. Like most serial killers, he has an established modius operondai. He kills entire families and, stealing a page from the Zodiac Killer, always leaves behind a cipher. To date, nobody has been able to crack his code.

Stranger still, each killing is staged to look like a murder-suicide perpetrated by the family’s patriarch. No physical evidence can place Longlegs at the crime scene. The man and his methods remain shrouded in mystery.

Longlegs shines when it lets us languish in the unknown and unseen. Its cryptic restraint is more disturbing than its brutal gore, at least to me, but Longlegs offers a hefty helping of both.

Perkins’ directorial sensibilities have a surreal streak, yet he avoids unnecessary trappings of stylistic excess. Watching the film feels like being in a nightmare, simultaneously zany yet plausible. Longlegs deftly walks a line between true crime and the occult. It falters a bit in its third act but never loses steam. Instead, the film answers some questions and leaves others to linger. It’s effective, if inelegant, nightmare fuel, bolstered by unsettling cinematography, a disquieting musical score, and a dreamlike editing style.

Cinematographer Andres Arochi’s compositions display a penchant for symmetry that is both stylish and uncanny. The film’s composer, Zigli (a pseudonym for Perkin’s brother, Elvis), weaves a textured tapestry of aural terror using whispers, discordant strings, and a foreboding bass. Greg Ng’s editing style omits connective tissue, creating sequences that adhere to the helter-skelter logic of nightmares.

It all combines into a noxious fever dream of Satanic Panic, brimming with gleeful malice, whose immersive style effectively preempts common complaints about characters in horror movies making “stupid decisions.” If you can engage with the film on its own terms, Longlegs offers well-constructed thrills and chills.

If you’re the type to complain when a character goes outside to investigate a strange noise, you may have problems with Longlegs, and movies generally.

Scouring films for “logical inconsistencies,” an inane form of criticism epitomized by CinemaSins, is a mode of cinematic engagement that actively resists immersion. These misguided viewers seek a level of logic and realism that film does not aspire to.

Cinematic language cuts superfluous information to facilitate narrative progression. Like dreams, film’s logic is not beholden to reality. It’s why there isn’t a scene of James Bond waiting at baggage claim or Harry Potter squatting over a chamberpot. Most films don’t strive for realism; they aim for some degree of verisimilitude.

Longlegs successfully emulates the experience of a nightmare with considerable aplomb. It isn’t as terrifying as its viral marketing professes, but Longlegs is a frightful delight worth the price of admission.

Until next week, \LL⊂ Ↄ⏁V⅂ ⨀Ω∴:⊥\ ⨀L ⊂—VL⊂— ⨀Ո:ᘰ ꇓ—ᘰᘰ•\—, my fellow film freak.