The history of popular film, and pop culture more generally, shows us that any form whatsoever – absurdist comedy, exploitative horror, pulp-trash fiction, tasteless parody – can be (and probably will be) applied to the events of our collective, real-life history; and that all sorts of unlikely insights may well be generated from these sometimes bizarre, mix-and-match experiments.”

-Adrian Martin in “The Offended Critic”

Last week in Acquired Tastes, a reflection on Damien Chazelle’s Babylon:

This week I’d like to continue with a consideration of Andrew Dominik’s Blonde, currently streaming on Netflix.

The Idea of Marilyn

What’s in a name? On this question, William Shakespeare and Norma Jeane Baker might disagree.

Marilyn Monroe.

She is woven into the fabric of American pop culture — her name, likeness, body, beauty, smile, laugh, distinctive mole, charisma, persona, her life, and her death.

The beloved icon’s specter, immortalized by her early and tragic demise, still lingers over the industry which arguably led to her death. Her influence continues to inspire contemporary personas, influencing artists like Megan Thee Stallion.

On her most recent album, Traumazine, Meg says, “Marilyn Monroe. My favorite ho. My favorite bad bitch, I think she the G.O.A.T.”

These words unironically revere Monroe. To be a “bad bitch,” to be Meg’s “favorite ho” whom she regards as the “Greatest Of All Time” — this is high praise in today’s parlance.

Meg does not drop Marilyn’s name flippantly. She does so on a track titled “Anxiety” during which Meg expresses difficulties within the industry that would have undoubtedly resonated with Marilyn:

“Sayin' I'm a ho 'cause I'm in love with my body

Issues, but nobody I could talk to about it

They keep sayin' I should get help

But I don't even know what I need

They keep sayin' speak your truth

And at the same time say they don't believe…”

-Megan Thee Stallion in “Anxiety”

Megan’s reverence for Marilyn, when considered in the verse’s broader context, hits a different chord. Invoking Marilyn’s legacy becomes an expression of distress.

“I'm really thinkin' 'bout dialin' 911 'til I freak

'Cause they probably won't think it's that deep

And I don't do drugs, so I never get a time when I'm at ease

I can't even handle smokin' weed

Marilyn Monroe, my favorite ho

My favorite bad bitch, I think she the GOAT

Jammin' to Britney, singin' to Whitney

I just wan' talk to somebody that get me…”

-Megan Thee Stallion in “Anxiety”

Marilyn Monroe died long before Megan Thee Stallion was born, and yet her legacy continues to resonate. Her persona is inspiring. Her stardom is aspirational. Her death is a cautionary tale.

I am also far too young to have shared this earth with Marilyn Monroe, but I knew who she was years before I would see any of her movies. For most of my life, Marilyn Monroe was an abstraction. She was sex, celebrity, fame — an inspiring icon and tragic figure. In my consciousness, she existed as an idea before I knew the name Norma Jeane Baker.

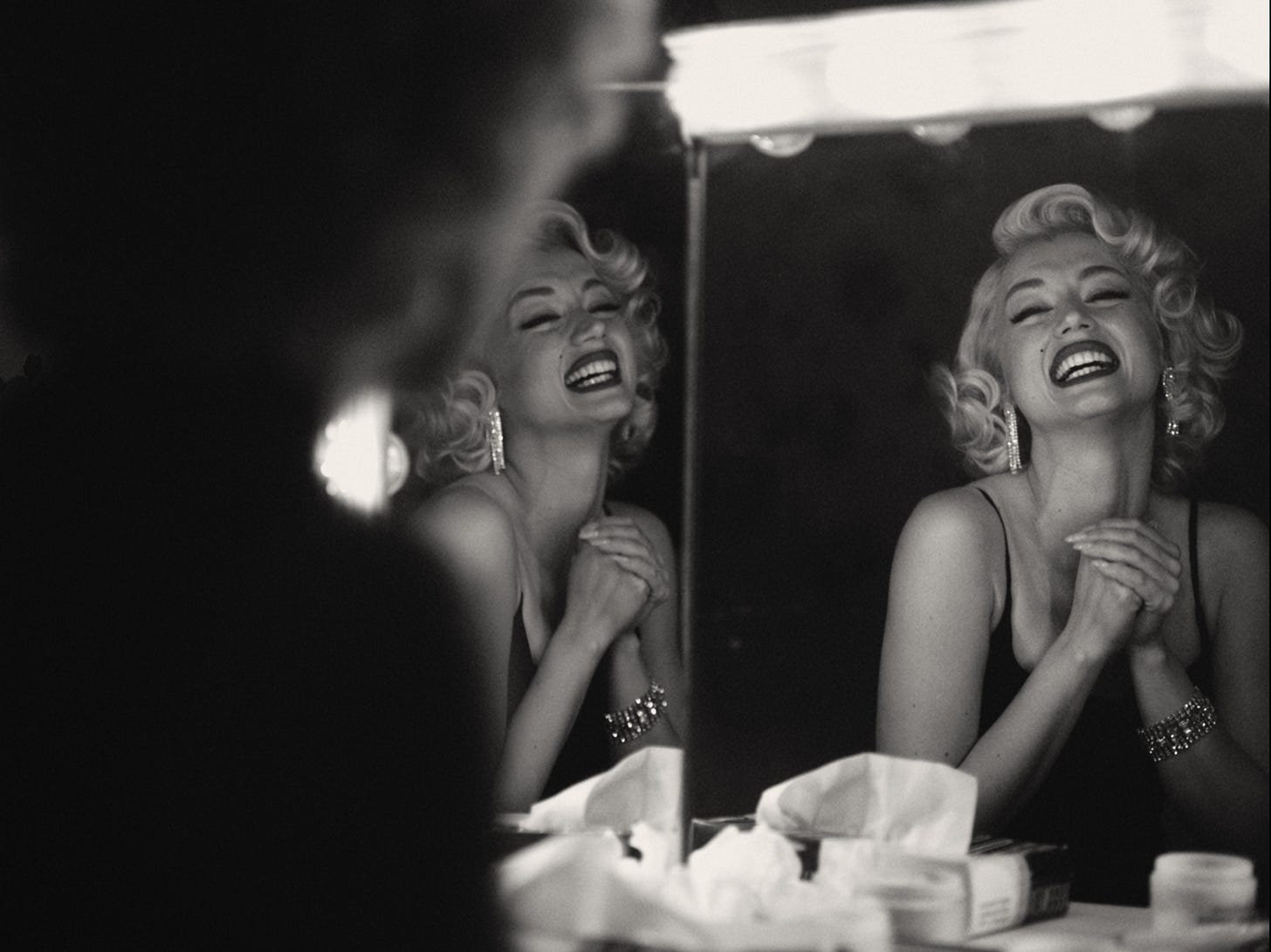

Andrew Dominik’s Blonde certainly piqued my interest and with Ana de Armas as Marilyn?!

You have my attention.

The Myth of Marilyn

“The myth of Marilyn Monroe is special because it combines three feminine personae. First, there is Norma Jeane Baker, the wholesome, normal girl with a naïve, vulnerable heart. …

The second persona is Marilyn Monroe, the pinup, bombshell, sex symbol, and movie goddess. She is the artificial creation of the Hollywood studio system, with a “sexy murmurous” name and a whispery, babyish voice… Marilyn is all body. Yet, paradoxically, behind that glittering, glamorous image, Marilyn bears the shame and self-hatred of living in a female body in a misogynist culture: fear of being unclean; disgust with her sexuality; a lifetime of menstrual cramps, gynecological problems, miscarriages, and abortions.

The third persona, the Blonde, is a symbol, the pure and virginal creature of fairy tales and religious parables. In popular culture and advertising, she stands for the upper-class, tidy, and stainless existence …Desired and worshipped as an ideal image of white beauty and class, the Blonde is nonetheless despised and defiled as a whore in pornography and fantasy.”

-Elaine Showalter’s Introduction to Joyce Carol Oates Blonde

The trailer for Blonde promises sumptuous visuals in a grandiose, and ostensibly sympathetic, retelling of Marilyn’s tragic plight.

Marilyn’s iconic vocals are slowed and slightly distorted. We are reminded that “men grow cold as girls grow old, and we all lose our charm in the end.” Blonde offers viewers a chance to know Norma-Jeane, who says of her Hollywood persona, “I can’t face doing another scene with Marilyn Monroe.” Dominik promises a portrait of Marilyn where she is “watched by all” but “seen by none.”

Watching Blonde begs the question: what does Dominik see in Marilyn? What, exactly, is he trying to show us? I can’t say for sure. Herein lies the problem with Dominik’s film.

Watching Blonde brings to mind a clip from Catfish that has become a meme. Within this scenario I am the woman in white, trying to ascertain why Dominik exhumed Marilyn’s legacy. Dominik is the woman in red:

For all the harsh words I have to say, I do not hate Blonde.

Upon rewatching, I was still offended by the film but it does not provoke the anger requisite for hate to fester. Instead, confusion is my primary response — not confusion concerning the plot of the film. It is the film’s sensibilities that vex me, and not in a good way.

I will assume that Dominik’s intent was noble, that he wanted to make a film that respected Marilyn Monroe and her legacy. I assume he is exploiting Marilyn’s life story to indict the dehumanization of women within the entertainment industry. I assume he is concerned with the prison of fame and the toxicity of stardom, and all the ways in which “living the dream” can be its own nightmare.

Alas, Dominik fails spectacularly. Most of my offense arises from a vulgar text whose intent remains obscure, or else hopelessly confused.

Andrew Dominik’s Blonde

“The various schools and methods of criticism devoted to close reading make their primary appeal to the text itself, rather than to broad social issues.”

-Adrian Martin in “The Offended Critic”

In Blonde characters will monologue, oftentimes incoherently. Sometimes they say exactly what they mean, clobbering viewers on the nose with clumsy symbolism.

Or, they flap their gums without saying anything at all. Early in the film, Norma Jeane has a three-way with the son of Charlie Chaplin and the son of Edward G. Robinson. This scene, as filmed, does not appear in the screenplay. I assume much of it was improvised because its content is remarkably strange.

Charlie Chaplin’s son, Cass, enters the room and says:

“This place… know what it smells of? Dreary old love-paste. Nothing more dreary than rancid love-paste. You know we’ve performed in porn films. Just for the hell of it. Not for cash.”

After an unhinged preamble about the smell of cum and shooting pornos, Cass seems to find his way to making a (blunt) statement about liberating the female body while, simultaneously, objectifying Marilyn. He undresses her before a mirror, saying:

“The human body is meant to be seen. Admired and desired. Not hidden away like some ugly, festering wound.”

Then Cass’ ramblings immediately careen off the rails again:

“I like to watch myself in the mirror. I like to watch myself on the toilet even. In our household, my father, Chaplin, was all the magic. He drew all the light into himself until there was nothing left inside me but numbness. Like sleep. Only in the mirror could I see myself. Anything I did in the mirror, I could hear waves and waves of applause.”

What am I to make of the fact that Cass watches his reflection while shitting? What does the thunderous applause that he hears every time he evacuates his bowels mean?

Then Cass seems to suddenly remember what movie he’s in and says of “Marilyn’s” reflection:

“Look, Norma Jeane. There she is. Your magic friend.”

When Blonde offers these head-spinning tidbits, its tone is quite serious. The stellar production design and costumes lend the aesthetic of prestige. Despite Dominik’s film considering itself “high art,” Blonde is as shallow as it is turgid.

In Blonde, subtly has been shot in the fucking head. You can find it in a shallow grave behind the studio, buried next to Tact. Blonde feels like the unwanted lovechild of a one-night stand between Showgirls (1995) and a shitty Tenessee Williams play. It wants so badly to be meaningful, but its attempts at profundity are hamstrung by the intellectual shortcomings of a middle school theater production. It certainly swings for the fences but misses by a mile.

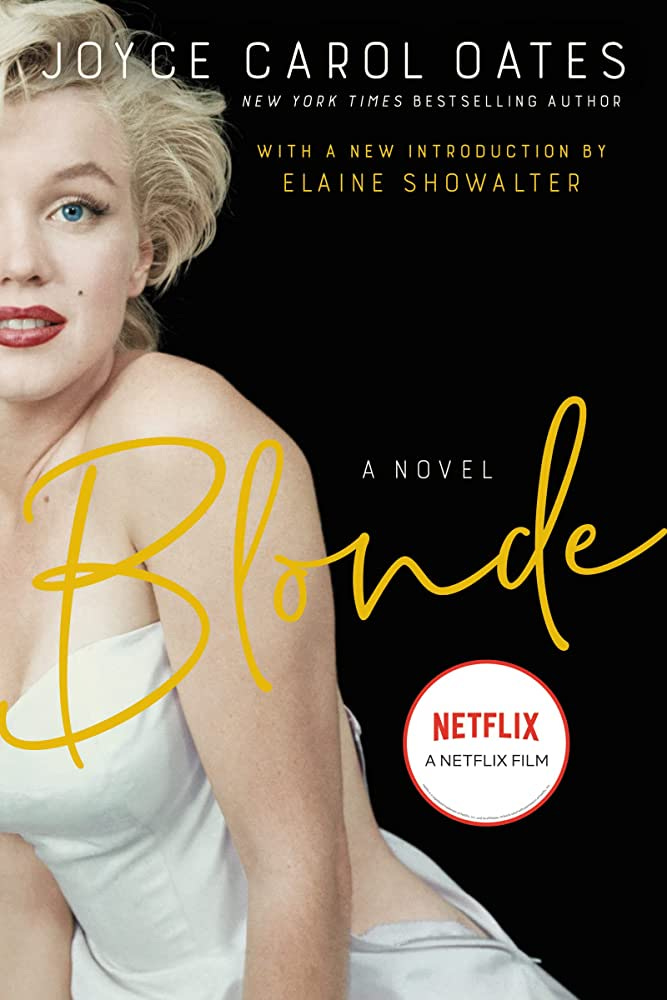

It is worth noting that Dominik’s Blonde is a cinematic adaptation of Joyce Carol Oates’ novel of the same name, which offers a fictionalized portrait of Marilyn’s life story.

Blonde by Joyce Carol Oates

“Oates pulls us into a book about the fate of a female star in the Hollywood world of mirrors, smog, and shadows, a world where women’s bodies are commodities traded for titillation and profit… Oates uncannily channels Monroe’s inner voice and demands that the star be given recognition, compassion, and respect… as Oates watched all of Monroe’s movies, learned more about her intelligence and humor, her determination to be seen as a serious actress, and the intersection of her career with multiple strands of mid-twentieth-century American culture—sports, religion, crime, theatre, politics—she realized that she needed a larger fictional form to explore a woman who was much more than a victim.

-Elaine Showalter’s Introduction to Joyce Carol Oates Blonde

Joyce Carol Oates’ Blonde, a novel almost 800 pages long, was released in 2000. Although the book is thoroughly researched and broadly resembles Marilyn’s life story, it is emphatically a work of fiction. It rearranges certain details, embellishes, and distills the life of Norma Jeane into a coherent work of fiction that attempts to unpack the manifold layers of the iconic “blonde bombshell” and the world she occupied.

…the book evolved and grew over two years of research and writing, she began ‘half seriously’ to think of Monroe ‘as my Moby Dick, the powerful galvanizing image about which an epic might be constructed, with myriad levels of meaning and significance.’ … Oates saw profound aspects to Monroe’s story that made it possible to think of her seriously as a tragic and representative American figure… in the words of one reviewer, who did not know Melville had been one of Oates’s models, she succeeded completely: ‘Blonde is a true mythic blowout, in which Marilyn is everything and nothing—a Great White Whale of significance, standing not for the blind power of nature but for the blind power of artifice.’”

“At the same time, Oates develops and deepens background themes inherent in Monroe’s story, including the growth of Los Angeles, the history of film, the House Un-American Activities Committee’s witch hunt for Communists in the film industry, and the blacklist. Each of these storylines could be a novel in itself, but, like the chapters on cetology and whaling in ‘Moby-Dick,’ they heighten the epic quality of the novel.”

-Elaine Showalter’s Introduction to Joyce Carol Oates Blonde

Oates infuses her version of Marilyn’s story with the sensibilities of a “gothic fairy tale” in which a “Dark Prince is a powerful male who imprisons the princess in a haunted castle.”

“The Studio stands for this macabre space, as Norma Jeane works her way up through a system run by ruthless, predatory men she must pacify, satisfy, and serve. Being ‘groomed for stardom,’ Oates writes, is ‘a species of animal manufacture, like breeding.’

Beyond the walls of The Studio are The Magi: gossip columnists, writers for fan magazines, and the tabloids. They are quasi-religious figures of the Church of Hollywood, but, also, like the evil witches of fairy tales, they are ‘there at the birth of the star and . . . there at the death.’”

-Elaine Showalter’s Introduction to Joyce Carol Oates Blonde

Oates’ novel seems like it effectively enters Marilyn’s mind, following her through a richly textured world of bright lights, red carpets, and golden cages. Joyce Carol Oates’ novel undoubtedly deconstructs Monroe’s complexity, propelling the legacy of the 20th-century icon into the new millennium. Marilyn Monroe has come to embody a vast multitude of meanings, a tragic mess of contradictions without resolution.

I am eager to read her novel and glean what insights she has to offer because Dominik’s film is nothing more than a hollow bombshell.

“A more literary tradition in cinema studies stresses artistic intentionality, aesthetic point-of-view, the precise mood and tone of a drama or comedy – in other words, just how (according to the critic’s reading) we as viewers are asked to consider, regard, or reflect upon what we see.”

-Adrian Martin in “The Offended Critic”

Oates commented on Dominik’s adaptation in an interview with The New Yorker. She had the same response as me and everyone else with whom I’ve discussed Blonde:

“I had to stop watching about midway through. The film is emotionally exhausting.”

Nevertheless, Oates remains quite charitable in her description of Dominik’s adaptation.

“It’s not a feel-good movie. Many films about Marilyn Monroe are kind of upbeat … This one is probably closer to what she actually experienced.”

“It’s a work of art. Andrew Dominik is a very idiosyncratic director, so he appropriated the subject and made it into his own vision. It’s grueling, though. It’s almost three hours long. I had to stop watching it, go away for a couple of hours, and come back. It’s demanding of the viewer.”

Critical Backlash to Dominik’s Blonde

“Reviews and op-ed commentaries determine, in ringing tones, whether a movie is sexist, misogynist, homophobic – or progressive, promoting fluid sexual identities; whether it is regressive and repressive or, on the other hand, liberating; whether it bolsters conservative, nuclear family values, or subverts them; whether it is militaristic, or pacifistic; whether it reinforces stereotypes and caricatures of races and nations, or expands them; whether it massages and perpetuates an exclusively bourgeois view of experience, or critiques it; whether it shows us, in a salutary fashion, the materialist, soulless emptiness of the modern world, or indulges and wallows in that emptiness. This is film criticism as social commentary…”

-Adrian Martin in “The Offended Critic”

Upon release, Dominik’s Blonde quickly became the subject of critical controversy.

I saw Blonde for the first time on October 1st, 2022. I will admit, the film surprised me. In truth, I expected to like it. I thought the critical response was overreacting to the film’s obscene or lurid content. Not easily offended, I thought I’d land amongst the contrarians.

Alas, Blonde was, and remains, the worst movie of 2022. There were less interesting, lazier films (e.g. Morbius) but Blonde was downright offensive, ponderous, and degrading toward its subject.

“The character endures an overwhelming series of relentless torments that, far from arousing fear and pity, reflect a special kind of directorial sadism. … It depicts Monroe as the plaything of her times, her milieu, and her fate, by way of turning her into the filmmaker’s own plaything. The very subject of the film is the deformation of Monroe’s personality and artistry by Hollywood studio executives and artists; in order to tell that story, Dominik replicates it in practice.”

-Richard Brody in“Blonde Is The Passion of the Christ for Marilyn Monroe”

Ana de Arma’s Marilyn, brilliant though her performance is, embodies a copy of a copy of the myth of Marilyn Monroe. She is, perhaps, the film’s saving grace. Blonde’s best moments are when Ana de Armas’ acting is the film’s focus. In the film’s final hour, as Marilyn begins to unravel, Ana de Armas channels her pain and anguish in a moving fashion.

Amid her remarkable performance, one gets the sense that Ana de Armas is fighting for her goddamn life, doing everything in her power to somehow manifest around her a better film that doesn’t fail her and her character so spectacularly.

“Paparazzi and the press intrude on her private life. Her adoring fans are slobbering perverts… They mistake her Marilyn Monroe persona for her real self, even though she considers it a pure product for public consumption, having little to do with her real personality. … Yet the film never gets close to suggesting who, indeed, the real person is.”

“There isn’t anything about the real-life Monroe’s politics, including her defiance of the press and the studio to marry Miller (who was subpoenaed by the House Un-American Activities Committee to testify about his former links to the Communist Party), her conversion to Judaism, and her own activism (including against nuclear weapons). There isn’t anything about the control that Monroe took over her own career by forming a production company in order to choose and develop her own projects; there isn’t anything about her early enthusiasm for movies or her discovery of modeling… There’s nothing of her effort to escape from poverty and drudgery, her serious and thoughtful efforts to develop her career; not a word about Monroe’s extremely hard work as an actress… whatever has to do with Monroe’s devotion to her art and her attention to her business is relegated to the thinnest of margins.”

-Richard Brody in“Blonde Is The Passion of the Christ for Marilyn Monroe”

Revisiting the film, I still find the text exceptionally offensive. Like Dominik’s intent, the film’s tone is difficult to ascertain.

Early in her career, when Marilyn is “discovered” by being sexually assaulted by the studio head, “Mr. Z,” there is a disturbing dissonance between what occurs on the screen and the non-diegetic music that accompanies it.

“Rather than dissociating form and content, cinema-idea and world-idea, I suggest we consider the category of sensibility – the sensibility of a film or artwork, which is always individual to a particular aesthetic object, although it invariably incorporates a myriad of impulses, conventions and traditions that bring along the baggage of their own histories.”

-Adrian Martin in “The Offended Critic”

Dominik pairs a violent sexual assault with Marilyn’s vocals from “Every Baby Needs A Da-Da-Daddy.” It’s a befuddling moment in which the film’s visuals and soundtrack seem to be at war.

These moments, when the tone and intent of the film are entirely unclear, are where the film loses me. As a viewer, I don’t know how I’m supposed to process Dominik’s film. I am comfortable sitting in ambivalence if the text is complex and the director has some underlying intention. I cannot fathom what Dominik’s trying to convey in this scene. Form and content clash in a way that feels demeaning toward the film’s serious subject matter. It’s as if Marilyn’s own words are mocking her.

Later, during an ostensibly consensual sex scene (the “fish bowl three-way”), Marilyn is shot in a way that directly parallels the way she was framed during her sexual assault. Why? What am I to make of this?

After Marilyn auditions for a film, there is the following exchange:

Marilyn has had an incredible audition (none of which is shown) and if my sympathies lie with Marilyn (and they do), this moment demeans her talent. The exchange is structured like a joke, but nothing about it is funny. None of the characters laugh. So why are we presented this moment in this way?

Is this meant to convey the oppressive sexism in Hollywood which degrades and objectifies the women it exploits? Maybe, but why does Marilyn have to be the butt of the joke?

The film barely recognizes Marilyn Monroe’s genuine talents as an actress, so moments like this further degrade Marilyn’s craft. She wanted to be taken seriously as an actress. Her wish goes unfulfilled. Her world, and the cinematic world Dominik constructs, is too committed to leering at Marilyn’s body.

Dominik’s film has no interest in getting inside Marilyn’s head. It obsesses over her body, even going so far as to compose shots in which the camera is situated inside Marilyn’s vagina, as a vaginal speculum is inserted to perform a nonconsensual abortion. Not once, but twice.

“The problem isn’t just what Dominik doesn’t imagine but what he does. He directs as if he defines poetry as using ten vague words where three clear ones would suffice, and then transfers that misconception to images.”

-Richard Brody in“Blonde Is The Passion of the Christ for Marilyn Monroe”

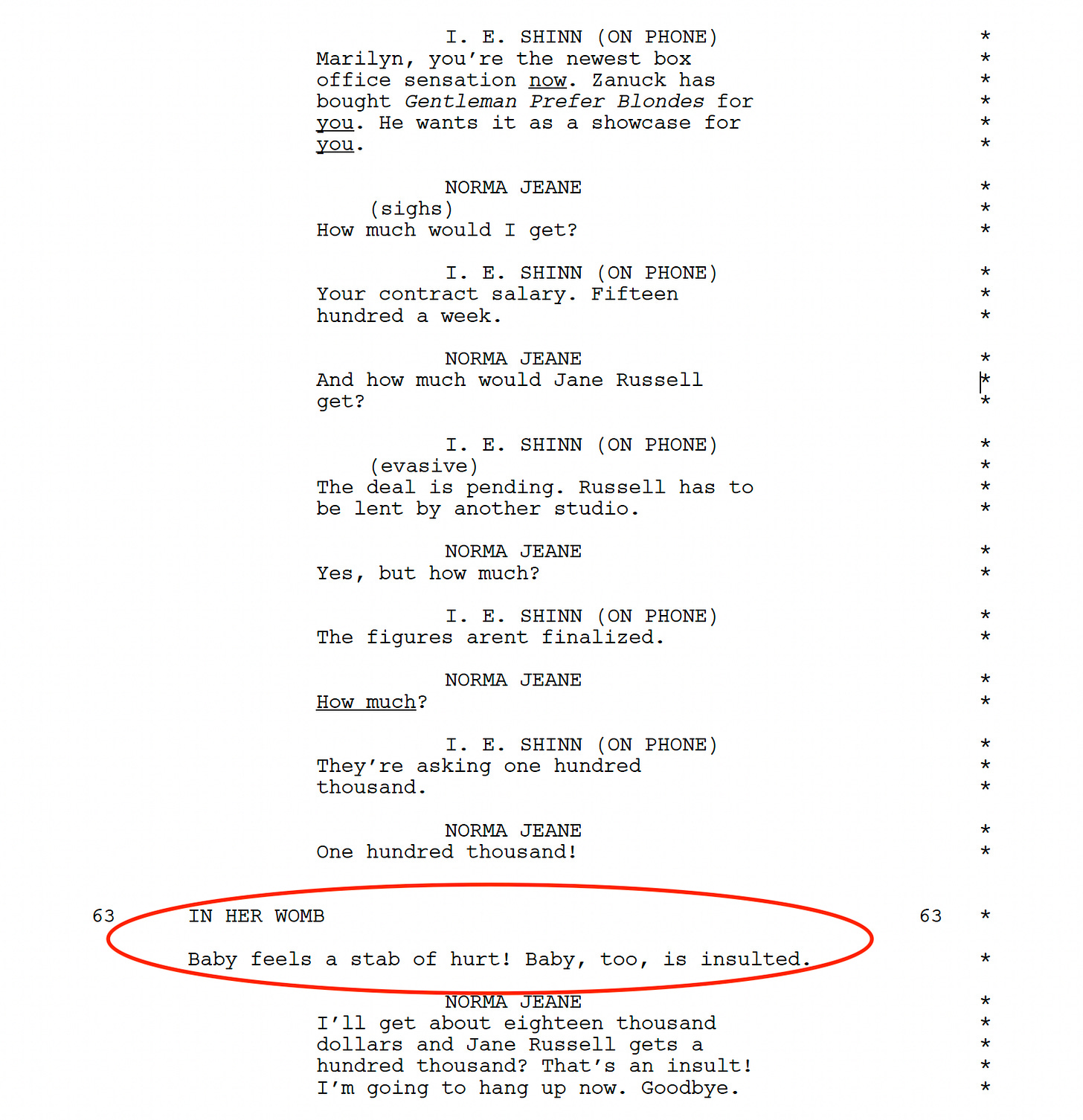

Dominik also takes numerous excursions into Marilyn’s uterus.

“Her fetus is …shown in the womb, and that fetus returns to the movie repeatedly, in C.G.I. fetus follies that ultimately involve it speaking to her… the straining for poignancy and subjectivity is done crudely and callously. A view upward and out, from the point of view of Marilyn’s vagina toward the abortionist, evokes Dominik’s own violation and misuse of the character’s body."

-Richard Brody in“Blonde Is The Passion of the Christ for Marilyn Monroe”

When the fetus tries to guilt trip Marilyn, it simply cannot be taken seriously. Yet, the incredibly strange creative choice calls into question Dominik's politics regarding a woman’s right to reproductive autonomy. I’m not offended by Dominik’s politics or that of his film, but I am deeply confused by the text. My feelings of offense arise from that confusion. Why am I being shown these things? As a viewer, they alienate me without discernable intent.

Why is Dominik so fixated on Marilyn’s womb? In his screenplay, her fetus has even more screen time. Someone had the good sense to cut the most ridiculous instances, but what remains is beyond the pale.

Blonde and the “Politics of Offense”

As I’ve been writing this piece, my opinions have evolved. Joyce Carol Oates also seemed to find the final hour most resonant, for many of the same reasons which I did. Her commentary struck me:

“The last quarter is very hallucinatory. Marilyn Monroe is addicted to barbiturates, and she’s suicidal; she’s losing her mind. She descends into a surreal world, one that is astonishingly vivid, and you almost feel that you’re losing your mind. I remember a certain immersion: it’s not a movie that you’re watching so much as being immersed in. Not for the faint of heart.”

“When she’s in the hallucinatory state and she’s being used by people whom she had revered and loved, or thought she’d loved, it’s heartbreaking.”

I considered Blonde as an immersive cinematic experience. Within that framework, the film’s goals shift completely. If Dominik’s film is attempting to depict Marilyn’s life by inflicting her pain onto audiences, then there are moments in which the film succeeds.

When a vaginal speculum spreads the walls of Marilyn’s vagina, I feel violated by the film’s shamelessness. The film makes me, the viewer, feel abused, exploited, and debased. Perhaps Marilyn and the viewer are meant to bond over shared trauma.

However, even when considered within this framework, Blonde remains a miserable viewing experience. It’s difficult to know if the film is a complete failure because its intent remains as mysterious as the icon it attempts to deconstruct, but simply cannot.

If Blonde is supposed to be taken seriously as an intellectual work of art, in the words of Joyce Carol Oates, “It’s demanding of the viewer.”

When Chaplin’s son rambles about watching himself shit in the mirror, am I supposed to cross-reference his bizarre behavior with Jacques Lacan’s writing on the “mirror stage” in developmental psychology? Or is this movie just a piece of shit waiting to be applauded?

If Blonde is intended as an intellectual titan, the film’s demands are unreasonable. Approaching Blonde as an immersive, avant-garde cinematic experience feels like “losing your mind.” Again, it asks too much of the viewer.

For me, the film remains offensive trash — interesting trash but trash nonetheless. Does my offense arise out of a “close-minded” response to the film, as Adrian Martin would suggest? I don’t think so. I grappled with the film for over a week as I wrote this piece. I tried to be charitable and give Dominik the benefit of the doubt.

Does any of this temper my offense when Marilyn is depicted as JFK’s semen repository? No, not at all. Whatever Dominik’s intentions, the film does not succeed. It is staggeringly uncouth.

When it comes to the politics of offense, rather than asserting that offense arises out of close-mindedness, it may be more productive for viewers to consider which types of cinematic experiences they are open to.

Perhaps a viewer is not open to being frightened by horror or cannot immerse themselves in musicals. Perhaps certain thematic material is too triggering to engage with. Defining the boundaries of your tastes and sensibilities can mitigate the likelihood of being deeply offended. Or, perhaps you are comfortable being offended and find value in interrogating your feelings of repulsion. Either way, there’s no wrong answer. I am proposing a non-judgemental personal inventory that, unlike Martin’s psychoanalytic framework, doesn’t imply that offense is always unjustified.

In Blonde’s case, Marilyn Monroe deserved better, and my offense certainly feels justified. Thank the lord for Ana de Armas, whose performance is the sole redeeming quality of the film.

A Letterboxd review sums it up quite nicely:

“if you watched this movie for ana de armas, you may be entitled to financial compensation”

-“tyler” on Letterboxd

Thank you for your time and attention.

If you haven’t already, subscribe to Acquired Tastes for a newsletter delivered to your inbox every Sunday:

Or, if there are other film freaks that you know, please:

If you’ve seen Blonde, I would love to hear your thoughts!

See you next week, my fellow film freak.

I look forward to discussing this thoughtful and thought-provoking commentary on "Blonde"--there's so much to unpack.