Recently, a new friend told me that “they didn’t like movies.” I’ve always taken such declarations with a heaping tablespoon of salt. You may not watch movies often, but I cannot fathom disliking them. Movies tell stories, and everybody likes stories — it’s just a question of finding stories that speak to you.

I’ve always considered “disliking movies” akin to “disliking music.” The world of music is so vast, there must be songs that will move you. Many of my friends are immersed in the world of music. They listen to new releases every weekend. By contrast, I rarely spend time searching for new music. As such, I don’t consider music a hobby, but I certainly like music. I mean, who doesn’t like music?

However, as my new friend expounded upon their disposition toward film, I began to understand their problem differently.

They were unenthused by cinema due to its short run time and predictable structure. Movies simply go through the motions, characters face obstacles that they will ultimately overcome as the film cruises toward a predictable climax and trite resolution. Broadly speaking, my friend felt like every movie was the same, and, broadly speaking, they’re right. There is a three-act structure that every movie operates within.

When I entered undergraduate film studies, I intended to pursue screenwriting. I learned that if you want your work to be produced by a studio, there are certain rules to follow. The structural template for a “successful screenplay” was offered in Syd Field’s 1979 book, Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting.

Field asserts that successful screenplays conform to this structure, even seemingly non-linear films. Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994), for example, still fits the paradigm.

Field’s framework is invaluable for aspiring screenwriters. It allows us to deconstruct iconic movies, offering a glimpse under the hood of the greatest stories ever committed to film. However, the structure’s ubiquity can make movies all feel the same. This, I believe, is the issue my new friend was speaking to.

Field claims that “successful screenplays” follow his structure, but it’s worth considering what a “successful” screenplay is. For those studying Field’s paradigm, mostly aspiring screenwriters and filmmakers, a screenplay is “successful” if it gets produced. However, as we all know, studios produce and release an abundance of derivative swill.

That is to say a “successful screenplay” is not necessarily a “good” screenplay. A “good screenplay” deftly operates within Field’s paradigm in unobtrusive ways. A “good screenplay” can result in a “great movie” that transcends its structure, transforming cinema’s rote structure into something novel, unrecognizable, and capable of surprising you.

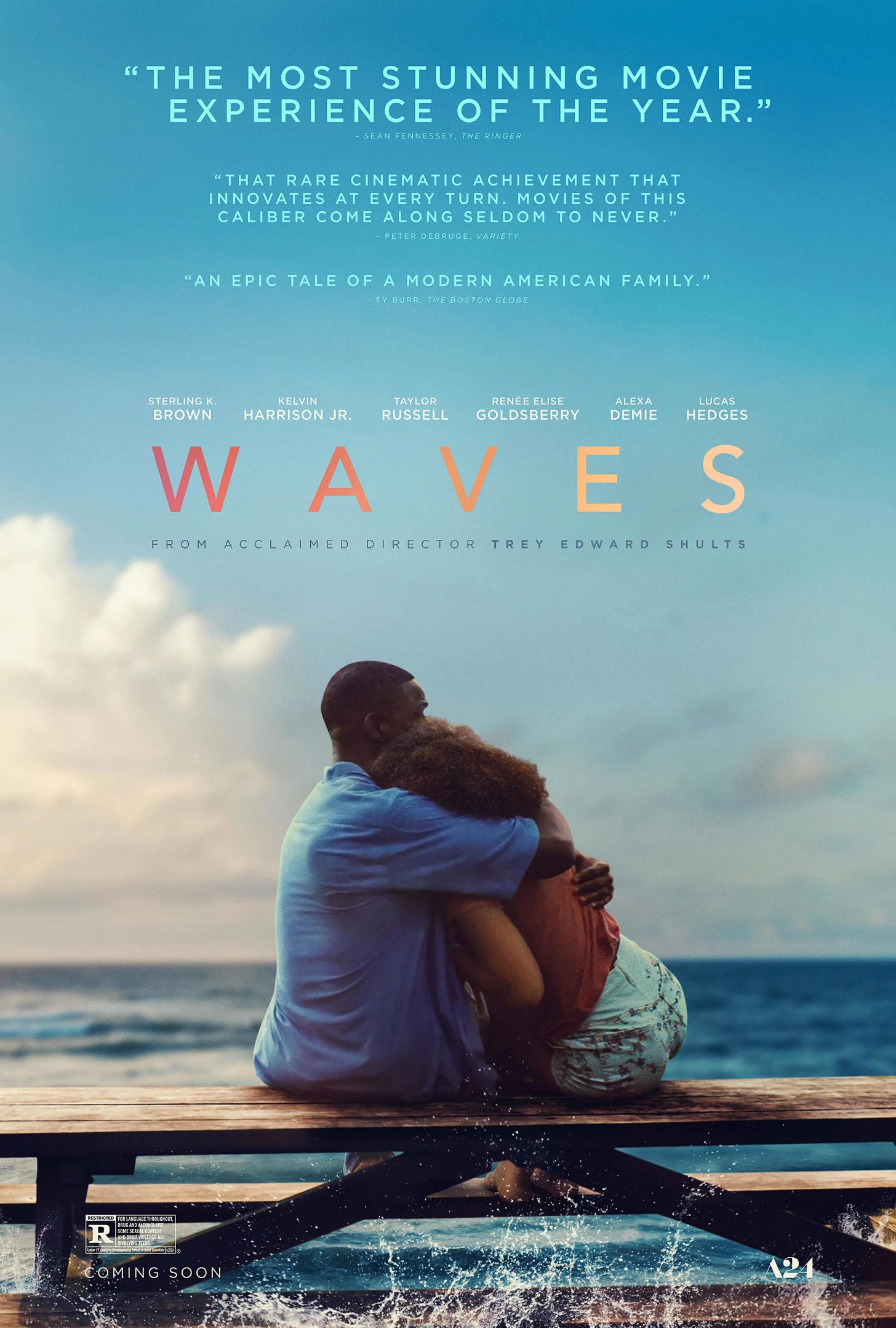

This week, I offer Trey Edward Schultz Waves (2019) for your viewing pleasure.

I watch a lot of movies. There are months when everything I see feels uninspired. Then, just as things begin to feel stale, I stumble upon a great movie that reignites my passion and reminds me why I love film.

Wading through the ocean of derivative bullshit and bringing the treasures I discover back to you, my fellow film freaks, is my primary function as an aspiring film critic. Sharing these exemplary films with others is among the greatest joys in my life.

Perhaps nobody expresses the experience of an art critic more succinctly than “Ongo Gablogian” from It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia (S11, E4):

After pontificating on the artistic merit of an air conditioner, Ongo spots a painting hanging among the derivative bullshit. It moves him deeply.

I bring up Waves rather often in casual conversation, and I’m surprised by how few people have seen it. Waves is a film emphatically worth watching and, in my opinion, the less you know the better.

I’ll simply say that Waves ranks among my favorite films. If you can, give the film a watch. I understand that requesting two hours of your time is a big ask. However, if you watch one movie this week, consider watching Waves.

This week, I am delivering a treasure direct to your inbox. Trey Edward Schultz’s Waves is available on Youtube, free with ads. Obviously, ads suck but if you have an ad-blocker browser extension (which you totally should), you’ll be able to view the film without ads.

Since Waves is rated R (for language throughout, drug and alcohol use, some sexual content and brief violence-all involving teens), the video is “age-restricted.” You’ll need to sign into YouTube. Google owns YouTube so signing in is rather seamless. You probably don’t even have to make a new account.

I leave you with this link, and I hope that you are as moved by Waves as I am.

If you haven’t already, subscribe to Acquired Tastes for a newsletter delivered to your inbox every Sunday:

Or, if there are other film freaks that you know, please:

What movies deeply move you? I’d love to know so, please:

See you next week, my fellow film freak.