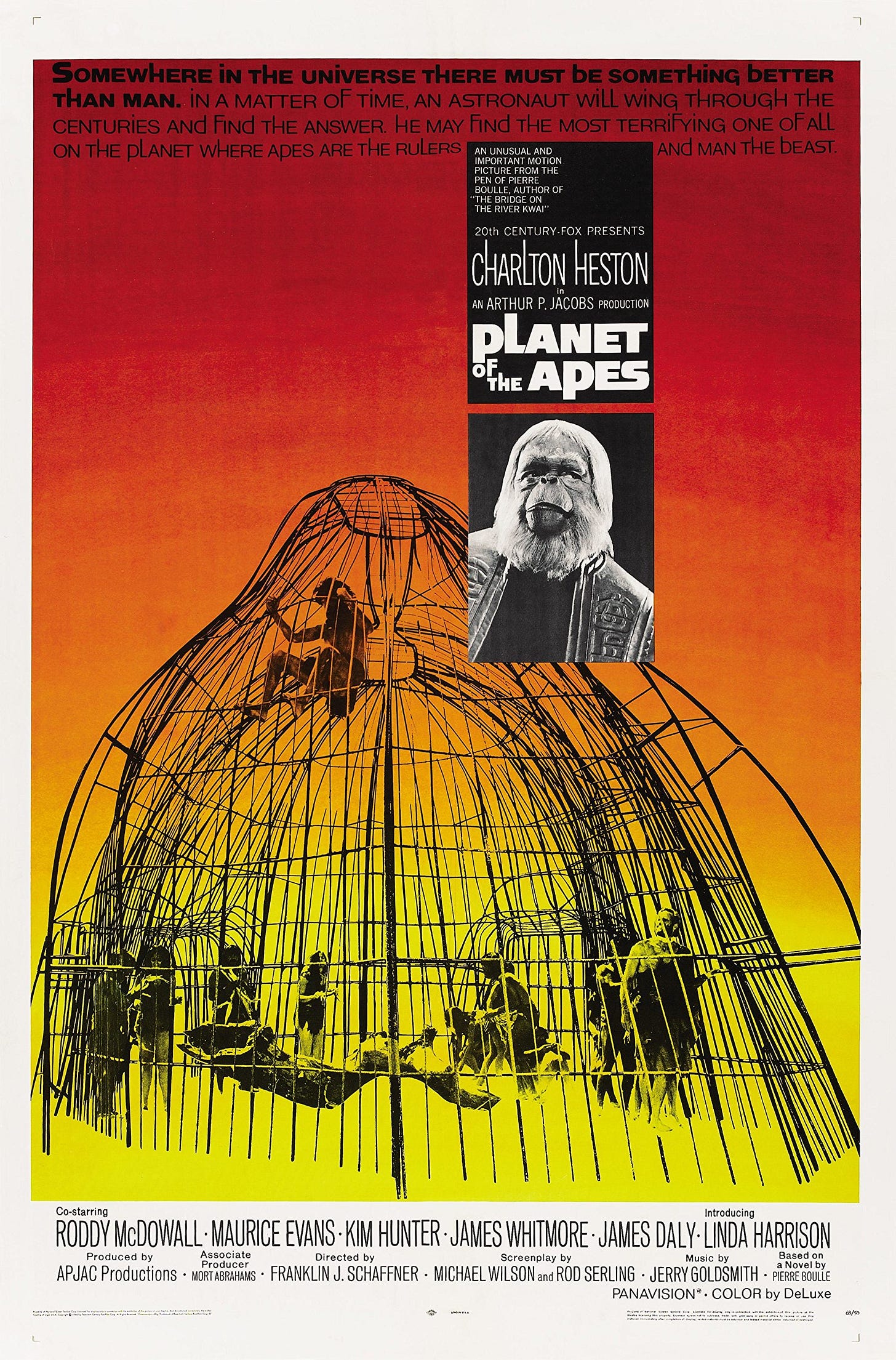

Planet of the Apes (1968) ⭐️⭐️⭐️1/2

Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes, the tenth film in the long-running Planet of the Apes franchise, releases in theaters on May 10th.

A few weeks ago, I polled you, my dear film freaks, to ask what new releases you wanted me to focus on. A Planet of the Apes retrospective won, securing 40% of the vote.

I’ll be honest, it was not the outcome I was expecting. However, as a man of my word and believer in democracy, I have rewatched the films and am prepared to offer my reflections. This week will focus on the original film.

Subsequent installments of this retrospective will focus on four sequels (produced between 1970 and 1973), a 2001 remake from director Tim Burton, three reboots (produced between 2011 and 2017) that function as pseudo-prequels, and, finally, Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes, whose trailer suggests narrative similarities to the original film.

Seeing as this is a retrospective, not a review, this article will include full spoilers for the Planet of the Apes franchise.

🚨Full spoiler alert for Planet of the Apes, a film released over 55 years ago.🚨

I first saw the original Planet of the Apes franchise in 2020, amidst the pandemic lockdowns. I consumed the films quickly and, in retrospect, without much critical thought. I didn’t know much about the films at that time. In truth, I purchased a Blu-ray box set of the original Apes franchise because it was on sale, and my mother had raved about how much she loved the films as a child.

With nothing but time and nowhere to go, I watched all the Planet of the Apes films. I considered their content through the lens of critical race theory, situated within the historical context of their production. To my surprise, I found the films rather arduous to view, mired in crude, muddled social commentary. The 1968 original left me disappointed, and the sequels devolve into absolute nonsense.

Have fond memories of the original Planet of the Apes?

Four years later, I’m grateful that I had the opportunity to revisit these films. The scope of my analysis, it turned out, was blinkered.

“Planet of the Apes has most readily been read as a civil rights allegory, but this does not allow for a complete understanding of the film and its cultural impact… When reviewing the entire franchise, race appears to be the most prominent issue across the films, but this reading relies upon viewing the franchise ‘as one great work’ […] and overlooks the fact that these films were conceived as individual works… Each film was produced in a specific historical moment by different production teams, each with its own set of cultural concerns and interpretive potential.”

“Other discourses are neglected when Planet of the Apes is simply evaluated as a franchise installment… it connects with a far broader spectrum of socio-political tensions than the later sequels, which are beset by overt allusions to US race relations.”

-“The Evolution of Planet of the Apes: Science, Religion, and 1960s Cinema” by Amy C. Chambers

Upon closer observation, Planet of the Apes utilizes the science fiction genre and its fantastical setting to levy a far more robust criticism of America, its ideals, history, and culture circa the late 1960s. Talking apes give philosophical speeches that hold a mirror up to society and allegorically expose humanity's irredeemably destructive nature. The result is a strange film, a family-friendly sci-fi romp that also languishes in existential despair rooted in contemporary anxieties.

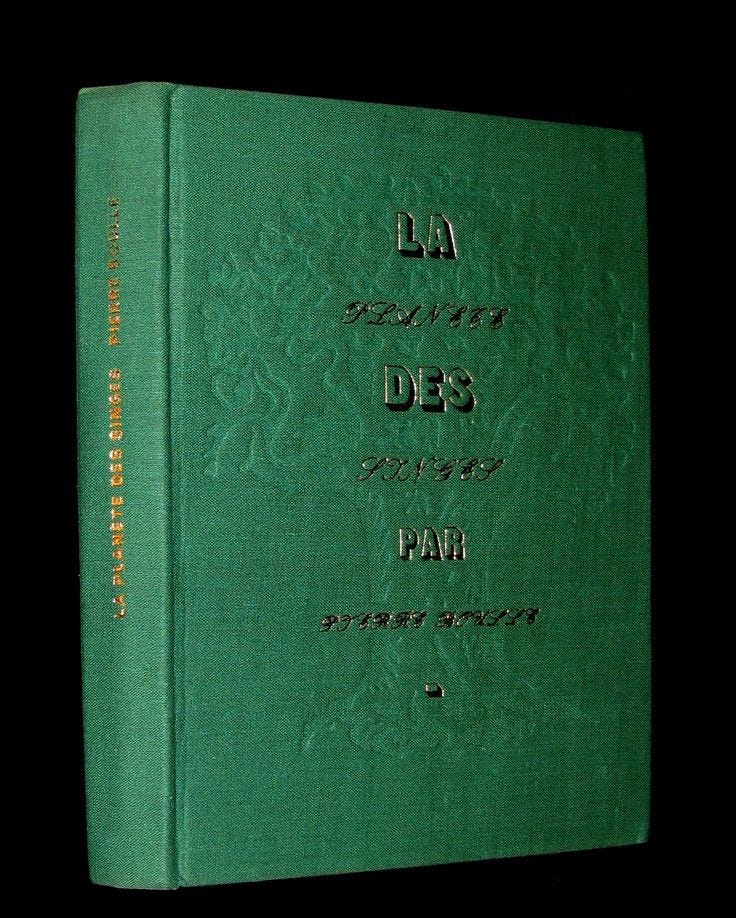

It is a fascinating study of cinematic adaptation as Planet of the Apes evolved from French author Pierre Boulle's novel, La Planète des Singes, to a film that was ultimately hamstrung by financial concerns at 20th Century Fox, a production company facing an uncertain future following runaway production costs for Cleopatra (1963), starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, and significant investments musicals including, Dr. Doolittle(1967) and Hello, Dolly (1969), that flopped at the box office.

“…budgetary restrictions in the early stages of development forced Serling to fundamentally alter one of Boulle’s focal points that positioned apes as replacing and surpassing humans both biologically and technologically. As cost issues became evident, the apes’ society culturally regressed to fit speculative film budgets… The technologically advanced simian society that had been originally envisioned by Boulle and then in part by Serling continued to deteriorate through each script revision as, first, budget and, then, studio requirements dictated a less advanced ape race… As the apes became less scientifically advanced, their faith became more prominent and an obstacle to science.”

-“The Evolution of Planet of the Apes: Science, Religion, and 1960s Cinema” by Amy C. Chambers

From La Planète des Singes to Planet of the Apes

Planet of the Apes is a franchise that takes itself very seriously. It grapples with weighty themes but lacked the resources to execute its original vision. The resultant film is different than Boulle’s novel, which used the scientific theory of evolution as the fulcrum of its social critique.

“In the source novel, Ulysse Mérou (a journalist) and a spaceship of scientists crash onto an alien, yet Earth-like, planet (Soror) run by a technologically advanced ape species. The reversed evolutionary scale is not the result of a nuclear holocaust; instead, the switch follows a much slower process of human devolution.”

“On Soror, the former human race becomes dependent upon their ape slave class, as the apes’ intelligence and aptitude increase, the humans become progressively idle, thus allowing the apes to rise to a position of power. The de-evolution of humanity is a narrative device to allow for the discussion of human nature rather than the intricacies of the biological theory.”

“Humans are used as test subjects in exploratory surgery and as a slave class by apes that consider themselves to be intellectually and ethically superior. The apes are shown to be technologically and culturally similar to the humans that preceded them, aping not only their achievements but also their arrogance. La Planète des Singes’s revels in anxieties about the nature and instability of power and the dangers of complacency.”

-“The Evolution of Planet of the Apes: Science, Religion, and 1960s Cinema” by Amy C. Chambers

Rod Serling, known for creating The Twilight Zone, was well-versed in genre fiction as a vessel for social commentary. He took a crack at the screenplay, setting the film in an advanced Ape society as described in Boulle’s novel, while also adding his own personal flair to the project.

“Rod Serling’s main addition to the film adaptation was the… ending, which supplanted La Planète des Singes’s evolution narrative… However, from Serling’s earliest treatments, the theme of evolution was secondary to the shocking … ending that ultimately allied the film to Cold War fears of nuclear annihilation.

When Serling stopped work on Planet of the Apes, the film focused upon the dangers of powerful authorities restricting science and knowledge rather than the evolution of a sophisticated ape species. The authority of the apes was not a natural oddity of evolution, as Boulle had envisioned, but, rather, the result of political and ethical failures of humans, drawing upon the fears and expectations of atomic war that were adroitly articulated in Serling’s shock ending.”

-“The Evolution of Planet of the Apes: Science, Religion, and 1960s Cinema” by Amy C. Chambers

An advanced ape society’s production costs would prove prohibitively expensive, and Serling would move on to other projects before Planet of the Apes began shooting. Nonetheless, his most essential contributions would remain in the next rewrite, and Serling and Boulle were both credited as screenwriters, alongside the third and final screenwriter, Micheal Wilson, who would imbue his own politics into the final screenplay for Planet of the Apes.

“Wilson was a well-respected Hollywood screenwriter who had first-hand experience of the oppressive nature of the Cold War and the establishment’s control over the life and living of individuals. He had proven his ability to deal with Boulle’s satirical prose when he co-wrote an adaptation of The Bridge on the River Kwaı¨ that won Boulle an Oscar for best screenplay in 1957. Wilson was unable to claim credit for his work at the time because the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) considered him an ‘unfriendly’ witness in the 1951 Hollywood trials.

Wilson’s rewrites of Planet of the Apes were inspired by his own experiences during the Hollywood trials… Wilson transformed the script into an ‘allegorical attack on the blacklist’ and a critique of the United States as a developed nation that ‘gags its artists and intellectuals for political reasons, forces them to confess and recant and suppress their role in history.’ Wilson used the script as a means of communicating his ideas concerning autocratic government and the restriction of freedom, whether it be artistic, political, sexual, or scientific.

In Wilson’s Planet of the Apes, the apes’ understanding of evolution falters as it is fused with their religious perspective and institutionalized prejudices. These inseparable parts of ape culture offer a comment not only on the need to have clear partitions between science, religion, and society but also on a general need for freedom of thought.”

-“The Evolution of Planet of the Apes: Science, Religion, and 1960s Cinema” by Amy C. Chambers

This is your final spoiler alert.

It begins on a spacecraft, its crew suspended in cryosleep. The ship’s captain, Taylor (Charlton Heston), gazes out into the void as he makes his final report before joining his crew in their dreamless sleep through time and space:

Taylor: And that completes my final report until we reach touchdown. We're now on full automatic, in the hands of the computers. I have tucked my crew in for the long sleep and I'll be joining them soon. In less than an hour, we'll finish our sixth month out of Cape Kennedy. Six months in deep space - by our time, that is. According to Dr. Haslein's theory of time, in a vehicle traveling nearly the speed of light, the Earth has aged nearly 700 years since we left it, while we've aged hardly at all. Maybe so. This much is probably true - the men who sent us on this journey are long since dead and gone.

You who are reading me now are a different breed - I hope a better one. I leave the 20th century with no regrets. But one more thing - if anybody's listening, that is. Nothing scientific. It's purely personal. But seen from out here everything seems different. Time bends. Space is boundless. It squashes a man's ego. I feel lonely. That's about it. Tell me, though. Does man, that marvel of the universe, that glorious paradox who sent me to the stars, still make war against his brother? Keep his neighbor's children starving?

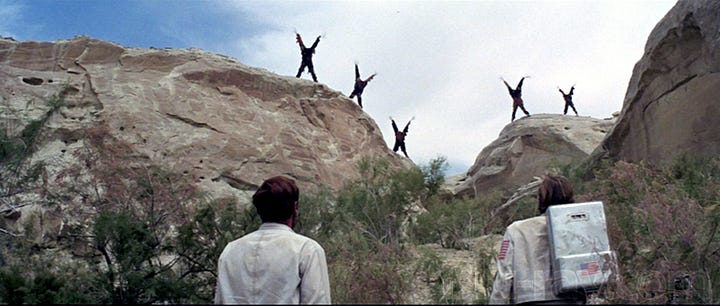

Their ship crashes onto an unknown planet, and the three surviving crew members, all men, wander a barren desert in search of life. For about thirty minutes, Planet of the Apes is a film about men wandering around sand and rocks. At first glance, it might seem unstimulating, but the sprawling, sparse landscape is a spectacle in itself. Its scale turns the men into ants. It is, in a way, indicative of the more naturalistic nature of Planet of the Apes otherworldly spectacle.

Beginning with contemplative monologues and long treks through arid wastelands, it’s easy to see why, at first glance, contemporary viewers may not be drawn into Planet of the Apes. I admit, upon first viewing, it wasn’t clear to me why Planet of the Apes is an enduring classic of the science fiction genre.

It’s difficult to take seriously a film where combat looks like children's playfighting. Every punch lands with four to six inches of visible distance between the fist and its target. Viewers looking for excitement, violence, and spectacle will be disappointed to find that, at times, Planet of the Apes feels more like a community theatre production than a sci-fi epic.

The shoddier aspects of the film’s craftmanship repeatedly break immersion, but the inability to suspend disbelief doesn't negate the film’s exemplary use of the science fiction genre’s unique capacity to render social commentary through allegory, metaphor, and subtext.

“Planet of the Apes tapped into endemic feelings of alienation from, and distrust of, the ‘establishment.’ In a similar fashion to notable New Hollywood films of the late 1960s… Planet of the Apes is structured around a complicated anti-hero, corrupt institutions, and a pervading hopelessness expressed through a disquieting, desolate conclusion…the church is the oppressive regime that restricts free speech by keeping alternative beliefs and histories suppressed; the apes are stand-ins for authoritarian figures; and the final cut of the film uses the well-trodden science-versus-religion discourse to engage with issues of institutional interference in individual freedoms.”

-“The Evolution of Planet of the Apes: Science, Religion, and 1960s Cinema” by Amy C. Chambers-

As a protagonist, Taylor is beset by contradictions. With blonde hair, blue eyes, and a rugged masculine demeanor, he looks like an astronaut from central casting. Clean-shaven and with short hair, he appears to be the epitome of the 1950s man. He is, however, discontented with life on Earth.

Taylor: Imagine me needing someone. Back on Earth I never did. Oh, there were women. Lots of women. Lots of love-making but no love. You see, that was the kind of world we'd made. So I left, because there was no one to hold me there.

He is a man adrift in the 1960s countercultural upheaval. He was lonely and, as his opening monologue suggested, slightly contemptuous of humanity and its cruelties. Despite this, he maintains a shred of optimism.

Taylor: I'm a seeker too. But my dreams aren't like yours. I can't help thinking that somewhere in the universe there has to be something better than man. Has to be.

Taylor and his crew soon find themselves among other humans, being hunted by apes on horseback. One of Taylor’s crew is shot and killed. Taylor and the rest of the survivors are rounded up and brought back to the Ape’s city for enslavement and scientific experimentation.

Ape society is stratified based on their subspecies. Orangutans sit atop the social hierarchy, led by Dr. Zaius (Maurice Evans), Minister of Science and Keeper of the Faith. Below them are chimpanzees, the intelligent middle class. Gorillas occupy the lowest strata, designated as uneducated hunters and warriors. It is no coincidence lighter skin among primate subspecies correlates with higher social positioning.

Taylor is separated from the rest and put in a cage with a woman whom he calls Nova (Linda Harrison). Nova and all the other humans have devolved and are incapable of speech, a fact that renders Taylor an anomaly.

Taylor’s unique capacity for speech catches the eye of Zira (Kim Hunter), a chimpanzee scientist who studies humans. Her curiosity endears her to Taylor, putting her and her husband, an archaeologist chimp named Cornelius (Roddy McDowall), in danger. Zira’s scientific pursuits would be seen as a heresy that directly negates the Sacred Scrolls, whose teachings govern ape society.

“The ape religion itself is not fully explained in terms of the exact rules and obligations in the film. But its development and detailed construction gives it a clear role with the film’s, and subsequently the franchise’s, abundant story world.”

“Wilson’s scripts introduced a more structured and pervasive ape religion with the sacred scrolls taking a central role in societal stagnation. The apes’ understanding of humanity is derived from holy texts, and they use these teachings as proof in place of scientific evidence.”

“The merging of faith, law, and science is evidenced throughout the ape story world from the phrases they use, to the arguments they make, to the costumes that they wear. Seemingly religious robes are worn all of the time—for example, those worn by the orangutan leaders are visually similar to vestments worn by both legal and religious figures, visually conjoining religion and state.”

-“The Evolution of Planet of the Apes: Science, Religion, and 1960s Cinema” by Amy C. Chambers

Tribunal of the “Three Wise Monkeys”

At the film’s midpoint, Taylor, Zira, and Cornelius face a tribunal of orangutans in a sham trial designed to malign Zira as a heretical risk to ape society. Screenwriter Micheal Wilson, inspired by his own experiences with McCarthyism and H.U.A.C, cleverly employed language evocative of Scopes v The State, a.k.a. the “Scopes Monkey Trial,” in which a Tennessee educator teaching the theory of evolution ran afoul of the powerful anti-evolution movement circa the 1920s.

In Planet of the Apes, faith and science are governed by one ape, Dr. Zaius, and the State weaponizes the legal system to further cement the centrality of faith over reason. Consider the following exchange:

PRESIDENT

State your case, Mr. Prosecutor.

HONORIUS

Learned Judges: My case is simple. It is

based on our first Article of Faith: that

the Almighty created the ape in his own

image; that He gave him a soul and a mind;

that He set him apart from the beasts of

the jungle, and made him the lord of the

planet.

278 CLOSE GROUP SHOT - THE DEFENDANT'S TABLE

Taylor has begun to write something on a sheet of paper. Zira and

Cornelius remain attentive to:

HONORIUS' VOICE

(o.s.)

These sacred truths are self-evident. The

proper study of apes is apes. But certain

young cynics have chosen to study man -

yes, perverted scientists who advance on

insidious theory called 'evolution.'

279 FULL SHOT - THE INQUIRY ROOM

As the Prosecutor continues:

HONORIUS

There is a conspiracy afoot to undermine

the very cornerstone of our Faith.

PRESIDENT

Come to the point, Dr. Honorius.

HONORIUS

Directly, Mr. President. This wretched man,

the accused, is only a pawn in the conspiracy.

We know that he was wounded in the throat at

the time of his capture. The State charges

that Dr. Zira and a corrupt surgeon named

Galen experimented on this wounded animal,

tampering with his brain and throat tissues

to create a speaking monster ...

ZIRA

(on her feet)

That's a lie!

PRESIDENT

(pounding gavel)

Mind your tongue, madame.

ZIRA

Did we create his mind too? Not only

can this man speak. He can write. He can

reason.

HONORIUS

He can reason? With the Tribunal's permission,

let me expose this hoax by direct examination.

PRESIDENT

Proceed. But don't turn this hearing into a

farce.

Honorius crosses to the defendant's table and favors Taylor with an

evil smile.

HONORIUS

Tell the court, Bright Eyes -- what is

the second Article of Faith?

TAYLOR

I admit, I know nothing of your culture.

HONORIUS

Of course he doesn't know our culture -

because he cannot think.

(to Taylor)

Tell us why all apes are created equal.

TAYLOR

Some apes, it seems, are more equal than

others.

HONORIUS

Ridiculous. That answer is a contradiction

in terms. Tell us, Bright Eyes, why do men

have no souls? What is the proof that a

divine spark exists in the simian brain?

“The tribunal is an investigation of Taylor as a contradiction of the law that unsettles the apes’ faith in their own superiority. Zira and Cornelius have posited an evolutionary theory that incorporates the notion that a biological link exists between apes and humans—a hypothesis that the orangutan council rejects on religious grounds.”

“‘Three wise monkeys’ see no evil, hear no evil, and speak no evil; they shield themselves from immorality and its temptations. Three injudicious orangutans turn a blind eye to anything that contradicts their religious dogma; they see no truth, hear no truth, and speak no truth. By rejecting science and restricting knowledge, the orangutans in Planet of the Apes (1968) have stunted the evolution of simian culture.”

-“The Evolution of Planet of the Apes: Science, Religion, and 1960s Cinema” by Amy C. Chambers

With the group’s guilt all but pre-determined, Zira helps Taylor mount an escape. Taylor, Nova, Zira, Cornelius, and their nephew Lucius venture into the Forbidden Zone. No longer safe in Ape civilization, they venture into the wasteland in search of evidence to support Taylor’s claims, be it the submerged remains of his crashed spaceship or archaeological evidence of a society that predated the Apes.

The group rides along the coast until they arrive at an excavation site Cornelius had illicitly visited years prior. Before they can enter the cave, they learn they have been followed. Dr. Zaius, supported by a group of armed gorillas, tries to stop the expedition from proceeding. Taylor manages to get the drop on Dr. Zaius who, in turn, demands his soldiers stand down. Dr. Zaius has no doubt that Taylor, whom he’s deemed a savage, will shoot him. Taylor and Zaius negotiate that if artifacts in the cave prove Zira’s theories, they will be exonerated. Zaius agrees.

Inside the cave, Cornelius and Zira present a variety of evidence to Taylor and Zaius. Zaius is not convinced by the tools and artifacts; he questions the validity of Cornelius’ archeological dating processes and insists that further investigation will prove that the cave was once occupied by an Ape master who kept humans for pets. Despite Taylor’s personal convictions, he agrees with Zaius that the evidence presented is not uncontestable proof that man is the missing link in ape evolution. Until that is, they find a doll resembling a human baby.

The doll itself doesn’t prove anything, but the doll’s ability to speak is incontrovertible proof of the missing evolutionary link. Why would an ape create a talking human doll if humans never possessed the capacity for speech? With the truth now revealed, Zaius reneges on his promises and attempts to have everyone killed. Taylor foils Zaius’ betrayal, ties him up, and learns the true nature of Dr. Zaius’s convictions.

TAYLOR

Cornelius has beaten you, Doctor. He

proved it. Man preceded you here. You

owe him your science, your language,

whatever knowledge you have.

ZAIUS

(quietly)

Then answer this: If man was superior,

why didn't he survive?

TAYLOR

(shrugging)

He might have been wiped out by a plague.

Natural catastrophe. Like a fiery storm

of meteors. From the looks of this part

of your planet, I'd say that was a fair bet.

ZIRA

But we can't be sure.

TAYLOR

(indicating Zaius)

He is. He knew all the time. Long before

your discovery, he knew.

(to Zaius)

Defender of the Faith. Guardian of the

terrible secret. Isn't that right, doctor?

389 REVERSE ANGLE - CIRCLE - FAVORING ZAIUS

As Zira and Cornelius look at him expectantly.

ZAIUS

What I know of man was written long ago

-- set down by the wisest ape of all --

our Lawgiver.

(to Cornelius)

Open my breast pocket.

Cornelius crosses to Zaius, and takes a small book bound in black

leather from the breast pocket of his tunic.

ZAIUS

Read it to him: the twenty- third scroll,

ninth verse.

Cornelius thumbs through the book, finds the citation and reads aloud:

CORNELIUS

'Beware the beast man, for he is the

devil's pawn. Alone among God's primates,

he kills for sport, or lust or greed.

Yes, he will murder his brother to possess

his brother's land. Let him not breed

in great numbers, for he will make a desert

of his home and yours. Shun him. Drive him

back into his jungle lair: For he is the

harbinger of death'.

Cornelius falls silent and looks down at Zaius.

ZAIUS

(quietly)

I found nothing in the cave to alter that

conception of man. And I still live by its

injunction.Taylor bargains for a horse, a weapon, and supplies. Against the protestations of Zira, Taylor insists on continuing forward on his quest for answers. To return to ape society is not an option for Taylor and Nova. They choose freedom and must forge ahead, into the unknown. Before departing, Taylor and Zaius exchange parting words:

ZAIUS

...All my life I've

awaited your coming and dreaded it.

Like death itself.

Taylor looks piercingly at Zaius, more troubled than offended.

TAYLOR

Why? From the first, I've terrified you,

Doctor. And in spite of every sign that

I'm an intelligent being who means no

harm, you continue to hate and fear me.

Why?

ZAIUS

Because you are a man. And you were right

-- I have always known about man. From the

evidence, I believe his wisdom must walk

hand in hand with his idiocy. His emotions

must rule his brain. He must be a warlike

animal who gives battle to everything around

him -- even himself.

TAYLOR

What evidence? No weapons were found in

the cave.

ZAIUS

The Forbidden Zone was once a paradise.

Your breed made a desert of it, ages ago.

TAYLOR

We're back at the beginning. I still don't

know the why. A planet where apes evolved

from men. A world turned wrong side up.

A puzzle with one piece missing.

ZAIUS

Don't look for it, Taylor. You may not

like what you find.Taylor and Nova venture up the coastline until Taylor stumbles upon a familiar sight that brings him to his knees.

“Released in 1968, the pivotal year ‘of the American decade,’ Planet of the Apes responded to the culture war that had been building throughout the post-war period. The film forms part of a collection of cultural forms that declared that the United States ‘seemed to be falling apart’... In the case of Planet of the Apes, this extended to a future where the United States had fallen apart.”

“The infamous closing shot of Taylor discovering the truncated remains of the Statue of Liberty is an iconic shot that devastatingly concludes the film by representing not only the destruction of the United States as a place but also, cathartically, its ideology (which is ironic considering the history of the statue itself).”

-“The Evolution of Planet of the Apes: Science, Religion, and 1960s Cinema” by Amy C. Chambers

On that somber note, the film ends, and the credits roll. The shocking twist ending, a brilliant addition by Rod Serling, ranks among the most well-known endings in film history. The film’s final image, Lady Liberty in shambles, is as haunting today as it was fifty-five years ago.

Faced with a resurgence of Christian nationalism, the rise of authoritarian governments and political charlatans, debates about free speech on the left and right, and a war of science vs. religion being waged in women’s uteruses across the country, one cannot help but wonder if Dr. Zaius was right about us all along.

Until next week, keep your damn dirty paws off each other, my dear film freaks.

Oh my, still pertinent today. Time to watch this again. Your notes layer more wisdom and reflection than I picked up or knew when watching in my youth. Thanks for the history lesson.