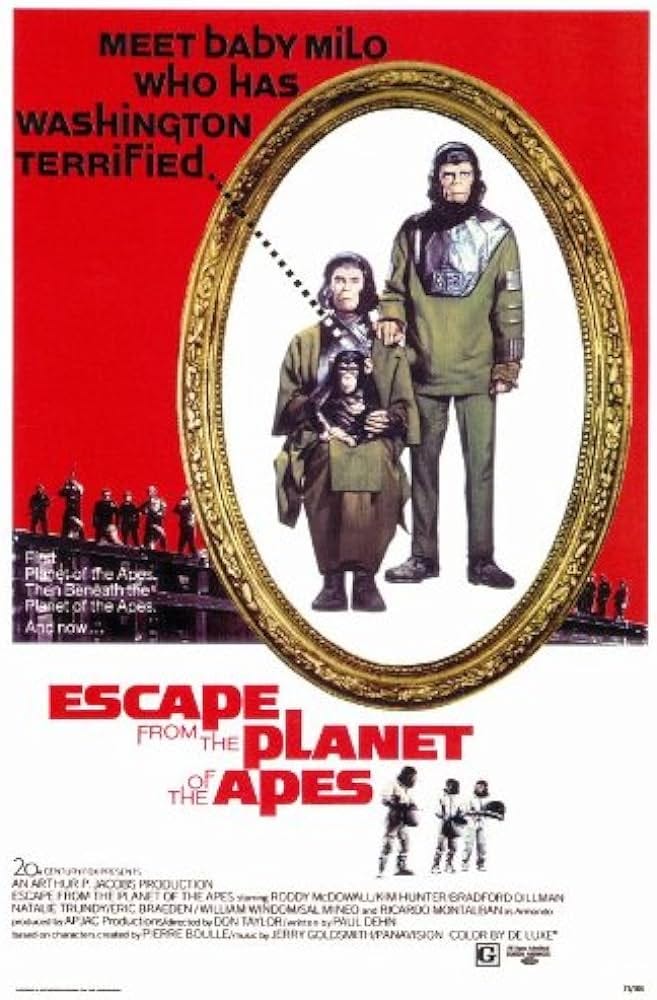

Escape from the Planet of the Apes ⭐️⭐️1/2

Escape from the Planet of the Apes is by far the most frivolous film in the series. It is a welcome reprieve from the previous film’s oppressive pessimism. It is, however, still a Planet of the Apes film. As such, its frivolity clashes with the series’ requisite social commentary, resulting in the most tonally and thematically inconsistent entry in the franchise.

It begins with a familiar sight: a spaceship crashlands into the ocean. This time, however, a helicopter circles the spacecraft. Three astronauts make their way to the shore, where they are greeted by the United States Army. The commander assumes Taylor has returned, but the astronauts remove their helmets to shock and surprise.

The army takes the apes into custody for observation, and their existence is kept secret. The apes hide their capacity for speech, begging the question of when and how they will reveal their true selves to contemporary humans.

The apes are sent to the Los Angeles Zoo to be studied by Dr. Lewis Dixon (Bradford Dillman) and Dr. Stephanie Branton (Natalie Trundy), who prove to be sympathetic enough for Zira to reveal her ability to speak.

The President of the United States briefs his generals on the Ape’s arrival, notes that they are friendly and sophisticated, and announces a Commission of Presidential Inquiry to be led by the President’s Senior Science advisor, Dr. Otto Hasslein (Eric Braeden).

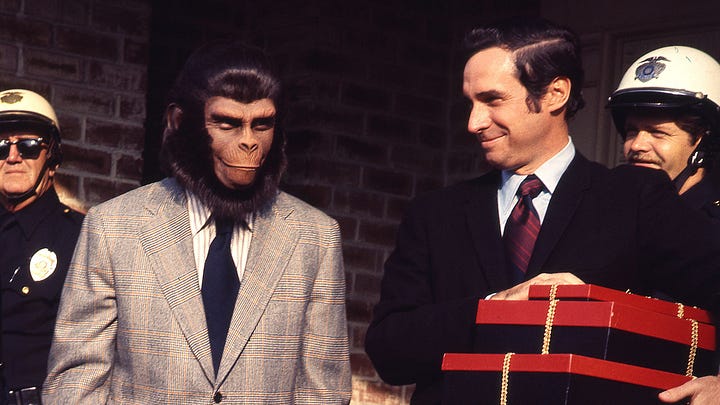

The press is invited to witness the Commission’s proceedings. Members of the Commission arrive and push through a throng of reporters asking for comment. Dr. Hasslein is the only one to comment.

Zira and Cornelius face this film’s tribunal, which includes politicians, journalists, spiritual leaders, and technocrats. The Committee is highly skeptical that apes can speak, but Zira’s cogent replies and Cornelius’ humor endear them to everyone except Dr. Hasslein.

When Cornelius is asked if they speak any language other than English, he doesn’t know what English is. He dissembles, saying that he speaks the language of his ancestors and is unsure of the language’s origin. He mentions that the gorillas and orangutans believe that God created apes in his own image, a statement that provokes Zira’s ire.

Zira: As an intellectual, Cornelius, you know damned well that the gorillas are a bunch of militaristic nincompoops and the orangutans a bunch of blinkered, pseudo-scientific geese.

Her denigration of her fellow apes elicits a hearty laugh from the gallery of reporters.

“Infinite Regression” and Aesthetic Distance

Later, Dr. Hasslein appears on television and waxes philosophical about the nature of time in an attempt to explain the impossibility of apes arriving from the future.

He posits that comprehension of time requires “a near God-like gift of infinite regression.” However, his explanation doesn’t really comport with the philosophical definition of infinite regress. Instead, his explanation focuses on an artist's painting:

Planet of the Apes is not a series known for its scientific accuracy. Previous installments have grappled with evolution despite only a cursory comprehension of Darwin’s theories. It’s no surprise that Escape from the Planet of the Apes isn’t actually equipped to grapple with epistemology. Instead, I believe the film's explanation of “infinite regression” is functionally an explanation of how audiences process social commentary in the film.

Dr. Hasslein’s description of the artist “taking a step back” is a rudimentary description of aesthetic distance:

“a tool used by artists in film and theater to create a sense of detachment between the audience and the work. This detachment can be achieved through a variety of techniques, including humor, symbolism, and narration. By forcing some distance from the subject matter, the audience can take a break from the weight of more intense scenes and emotions. The use of aesthetic distance is particularly effective in works that deal with heavy or challenging subject matter, as it allows the audience to process the content without becoming consumed by it…

Understanding aesthetic distance can dictate authorial approach to storytelling and characterization. By intentionally creating a level of aesthetic distance, writers can challenge their audience to engage more critically with their work. The use of aesthetic distance also allows writers to create complex and layered characters that require interpretation and analysis.”

-"What Is Aesthetic Distance in Film + Theater?” by Jennifer Lane

Hasslein defines infinite regression as the moment “where our artist regresses to the point of infinity, and himself becomes part of the landscape he painted, and is both the observer and the observed.” His example displays a certain self-awareness within the artist that, in today’s parlance, might be called “meta.” This digression into “infinite regression” is not apropos of nothing. Considering the ways that the Planet of the Apes franchise has utilized the science fiction genre to reflect on sociopolitical issues and contemporary cultural anxieties, what are viewers if not observers and the observed?

Much to think about. Much to consider.

America Loves the Ape-onauts

In modern fashion, the media mediates the public’s perception of the “ape-onauts.” Zira and Cornelius are treated to a room at the Beverly Willshire Hotel and a tour of Los Angeles. This is Planet of the Apes at its silliest: the couples have a shopping montage, Zira takes a bubble bath, Cornelius mixes it up with reporters, and Zira discovers the wonders of champagne (a.k.a. “grape juice plus”).

These breezy interludes still include scraps of substance. At a boxing match, Cornelius calls the bloodsport “beastly,” and Zira speaks to the Bay Area Women’s Club.

“A marriage bed is made for two. But every damn morning, it's the woman who has to make it. We have heads as well as hands. I call upon men to let us use them!”

-Zira, feminist icon.

During a tour of The Natural History Museum, Zira faints upon seeing taxidermied apes. Dr. Hasslein comes to her aid, assuming she is in shock. Zira denies shock and, instead, confesses that she is pregnant.

This is the first time Zira has mentioned her pregnancy. Why she offers this information to Dr. Hasslein is unclear, and the reason for her admission has no causal relationship with the preceding events. Simply put, it’s poor writing.

Back in their hotel, Dr. Hasslein attempts to extract more information about the future from whence the “ape-onauts” came. He plies Zira with alcohol, assuring her that it is “an excellent restorative, especially in cases of pregnancy.” She drunkenly divulges the truth, talking about the war depicted in Beneath the Planet of the Apes and the total destruction of Earth. Observing nuclear armageddon from orbit, the blast sent Zira’s ship hurtling backward through space and time.

A Darker Turn…

Dr. Hasslein takes his findings to the President. Zira’s confession has convinced Hasslein that apes pose a threat to humanity’s superiority and that a war with apes will inevitably result in the world’s destruction, sometime around the year 3950. The President remains unconvinced.

PRESIDENT: Now what do you expect me and the United Nations -- though not necessarily in that order -- to do about it? Alter what you believe to be the course or the future by slaughtering two Innocents -- or rather three, now that one of them's pregnant? Herod tried that, and Christ survived.

HASSLEIN: Herod lacked our facilities.

PRESIDENT: He also became unpopular. Historically unpopular. And we don't want that, do we?

HASSLEIN: Are you actually saying—

PRESIDENT: I'm saying that our two visitors seem really very charming and peaceable people -- or rather creatures -- and that the voters love them.

HASSLEIN: Do you want them and their progeny to dominate the world?

PRESIDENT: Well, not at the next election. But one day, if the progeny turn out to be as nice as the parents-- who knows? They might make a better job of it than we did.

A president who is compassionate, politically short-sighted, or both regards Dr. Hasslein's concern as alarmist. Further discussion of Zira’s pregnancy and the distant future provokes the “baby Hitler question,” foreshadowing the film’s drastic shift into darker thematic territory.

The Presidential Commission meets in secret and decides to remove the apes from the public eye and turn them over to the C.I.A. for interrogation. Zira is pressed over discrepancies between her formal answers to the Presidential Committee and her drunken replies to Hasslein’s inquiry.

Hasslein wants to know how humanity devolved and how Apes ascended. Cornelius and Zira’s answers offer a bounty of exposition and lore that will continue to develop subsequent films:

CORNELIUS: It began, in our prehistory, with the plague that fell upon dogs.

ZIRA: And cats.

CORNELIUS: Hundreds and thousands of them died. And hundreds and thousands had to be destroyed to prevent the spread of the infection.

ZIRA: There were dog bonfires…

CORNELIUS: By the time the plague was contained, Man was without pets; and for Man, this was intolerable. He might kill his brother, but he could not kill his dog. So Humans took primitive Apes as pets.

ZIRA: Primitive and dumb, but still twenty times more intelligent than dogs or cats.

CORNELIUS: They were quartered in cages, but they lived and moved freely in human houses. They became responsive to human speech. And in the course of only two centuries progressed from performing mere tricks to performing services.

INTERROGATOR: Like sheep dogs ...

CORNELIUS: Could a sheep dog cook? Could a sheep dog clean the house? Or go marketing for groceries with a list from its mistress? Or wait on tables?

ZIRA: Or, after three more centuries, turn the tables on their owners?

HASSLEIN: How?

CORNELIUS: They became alert to the concept of slavery and, as their numbers grew, to slavery's antidote, which is unity. They began to assemble in small bands. They learned the art of corporate and militant action. They learned to refuse. At first they barked their refusal. And then, on a historic day commemorated by my species and fully documented in the secret scrolls, there came an Ape called Aldo, who didn't bark. He articulated. He spoke a word which had been spoken to him, time without number, by Humans. He said “No.”

Dr. Hasslein zeroes in on a moment of Zira’s testimony before the Presidential Committee: “As to humans, I’ve dissected—examined thousands of them.” He injects sodium pentothal into Zira’s arm, and its disinhibiting effects once again induce a confession from Zira: yes, she has performed countless scientific experiments on humans, alive and dead.

Dr. Hasslein brings this information to the Committee, which renders its final verdict:

CHAIRMAN: By a majority vote, the Commission finds no solid evidence for hostility by either Ape towards the Human Race as at present constituted in this year of our Lord, nineteen seventy-three.

The male's attitude is that of a deeply interested and well-disposed academician who studied the alleged future downfall of the Human Race with the true objectivity of a good historian.

The female's case is different, in that she undoubtedly committed actions against the Human Race of a sort which, if they were to be committed today, would be called atrocities. But would they be so-called in two thousand years' time, when it is alleged that Humans will have become dumb brutes with the restricted intelligence of animals? It has been pointed out that what Apes will do to Humans is no more than Humans are now doing to beasts.

Nonetheless, the Commission is sympathetic to Dr. Hasslein's conviction that the progeny of these Apes could, in the centuries to come, prove an increasing threat to the Human Race and conceivably end by dominating it. This is a risk we dare not ignore.

Therefore… The Commission unanimously recommends that the birth of the female Ape's unborn child should be prevented; and that, after its prenatal removal, both the male and the female should humanely be rendered incapable of begetting or bearing another. Thus, the parents can still be employed to serve the community in a manner to which their undoubted talents are best suited.

What began with bubble baths and shopping sprees has, in a manner true to the series’ ethos, returned to serious questions surrounding the ethics of scientific experimentation on animals, reproductive autonomy, forced sterilization, and eugenics.

There’s no such thing as a happy ending…

Zira and Cornelius, now locked in a cell, seize an opportunity to escape. Cornelius attacks and kills a guard, and the two chimps sneak out of the military compound’s front gate in ridiculous fashion. Shortly after fleeing into the hills, Zira goes into labor. Hasslein and Dixon learn of the ape’s escape, and Hasslein’s ensuing panic recasts his zealotry in a new light:

INTERROGATOR: Don't worry. We'll catch them, sooner or later.

HASSLEIN: That's what I'm worried about. Later. Later we'll do something about pollution. Later we'll do something about the population explosion. Later we'll do something about the nuclear war. We think we've got all the time in the world, but how much time has the world got? Somebody has to begin to care.

There is no doubt that Hasslein intends to kill Zira and Cornelius, but he doesn’t act out of hatred. Instead, his motivations are rooted in his desire to build a better world for humanity. He refuses to differ the problem, as our government so often does in the face of existential threats. He will act in accordance with his conscience, even if it means murdering our protagonists.

Luckily, Dr. Dixon and Dr. Stephanie Branton are the first to find Zira and Cornelius. They take them to a traveling circus run by a friend, Armondo (Ricardo Montalbán).

Zira gives birth and names her baby Milo. As the rest of the group formulates a plan, Zira secretly swaps Milo with a different newborn chimp, the only one to be born in a circus, and entrusts Milo to the maternal chimp, Heloise.

Armondo’s circus is set to leave town in a few days’ time, and he offers Zira and Cornelius safe passage to the Everglades. However, with the ongoing search, they cannot remain with the circus lest Hasslein come looking. Instead, they must hide in a naval scrapyard that Dr. Dixon played in as a child until the circus is ready to leave town.

Before departing, Cornelius makes an unexpected request:

CORNELIUS: If we are caught, we will almost certainly be killed. Please give us the opportunity... to kill ourselves?

ZIRA: [holding baby] Please!

DR. DIXON: I shouldn't do this, but I guessed you'd ask.

[Dr. Dixon hands Cornelius a gun]

In the film’s final ten minutes, Dr. Hasslein tracks Zira and Cornelius to the shipyard. Cornelius traipses around the derelict ship in search of a cleaner room for Zira to feed their baby. Meanwhile, Dr. Hasslein removes a gun from the trunk of his car and confronts Zira, holding her at gunpoint and demanding she turn over the baby.

Helicopters approach and police and army vehicles arrive, surrounding the ship with armed officers. Dr. Dixon’s dumpy station wagon arrives on the scene. Zira makes a run for it but is shot in the back by Dr. Hasslein. The rest unfolds very quickly.

The image of Cornelius and Zira lying dead dissolves into an image of a circus tent being taken down. Armondo’s circus is leaving town. He pats the baby chimp on the hand and says, “Intelligent creature. But then so were your mother and father.”

Armondo exits the frame with a knowing smile and the baby Milo repeats his first words, “Mama,” as the screen fades to black. The baby chimp desperately cries for its mother as the credits roll.

So ends another installment of The Planet of the Apes, delightful family fare that ends with the ruthless slaughter of innocent (ape) men, women, and infants. Nevertheless, Escape from the Planet of the Apes was another financial success.

Setting the film in contemporary Los Angeles allowed production to shoot on-location and avoid constructing expensive, otherworldly sets. A budget of $2 million reaped $12 million in box office returns, and the next film would be released one year later.

What lies ahead for baby Milo in Conquest of the Planet of the Apes (1972)?

(Hint: the answer is sorta in the title.)

Until next week, don’t shoot any babies, film freaks.