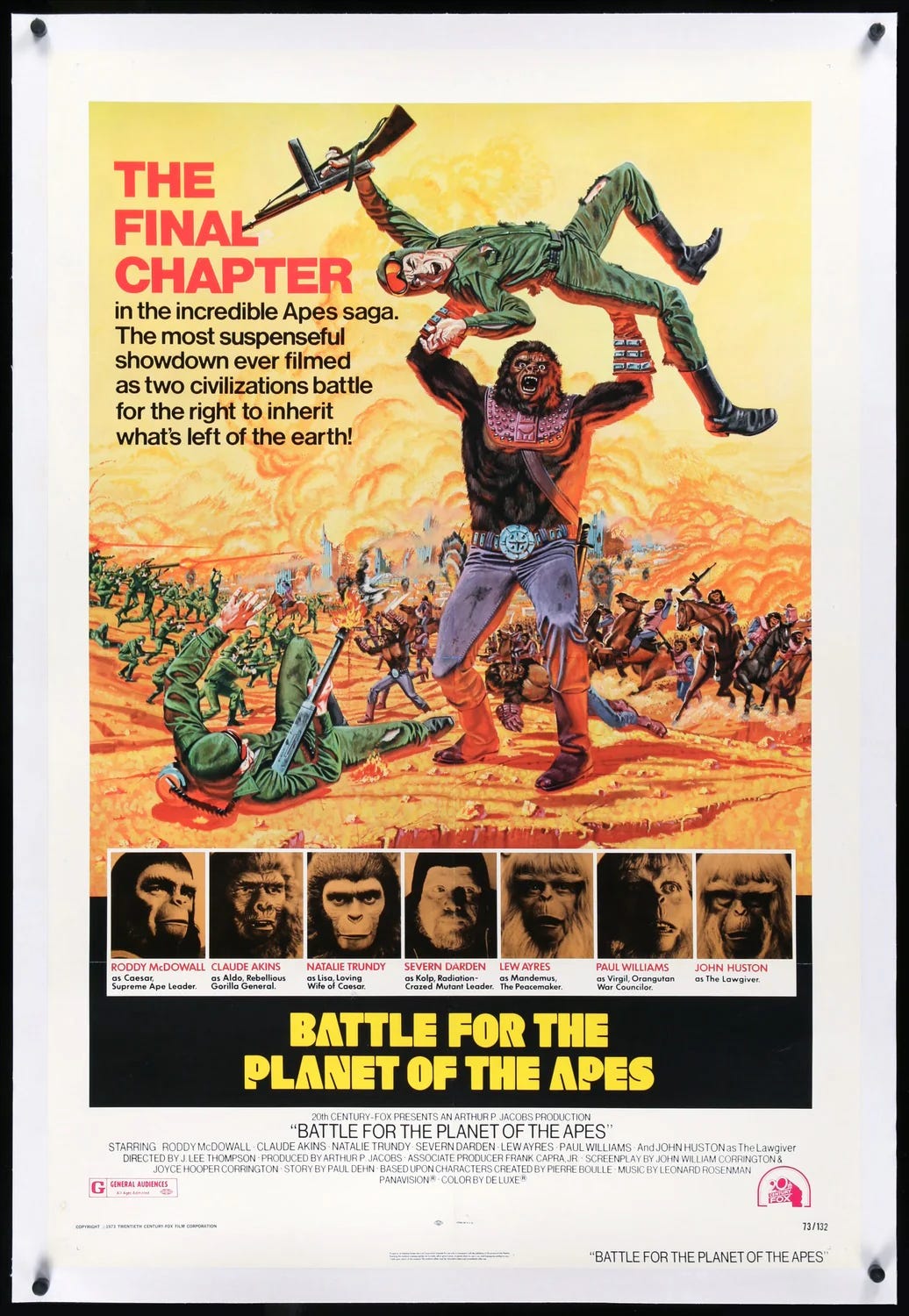

Battle for the Planet of the Apes ⭐️

In the beginning, God created beast and man so that both might live in friendship and share dominion over a world at peace. But in the fullness of time, evil men betrayed God's trust and, in disobedience to his holy word, waged bloody wars not only against their own kind but against the apes, whom they reduced to slavery.

Then God, in his wrath, sent the world a savior miraculously born of two apes who descended on Earth from Earth's own future. And man was afraid for both parent apes possessed the power of speech.

So both were brutally murdered. But the child ape survived and grew up to set his fellow creatures free from the yoke of human slavery.

Yet, in the aftermath of this victory, the surface of the world was ravaged by the vilest war in human history. The great cities of the world split asunder and were flattened.

And out of one such city, our savior led a remnant of those who survived in search of greener pastures where ape and human might forever live in friendship according to divine will.

His name was Caesar and this is his story in those far-off days.

-Lawgiver’s reading from The Sacred Scrolls in 2670 A.D.

It’s telling that the “epic” conclusion to the original Planet of the Apes saga, Battle for the Planet of the Apes, begins with a lengthy monologue from an unnamed orangutan reading from The Sacred Scrolls.

It is, in part, a recap of the previous two films: Escape from the Planet of the Apes and Conquest of the Planet of the Apes. More importantly, it functions as a framing device for the ensuing events. Despite the title, war is not the film’s focus. Once again, law and faith drive the story.

In that regard, the opening harkens back to the thematic successes of Planet of the Apes (1968). The original film facilitated a relatively nuanced exploration of religious fanaticism’s hostility towards scientific advancement and the subsequent perversion of law, truth, and justice.

Battle for the Planet of the Apes pulls on the same thematic threads to weave a more facile religious parable about the most obvious, egregious violation of morality: Ape shall not kill Ape.

In screenwriter Paul Dehn’s original vision for the fifth and final installment, Ceasar rules as a despot. He perpetuates the cycle of violence, inflicting upon humans the same cruel indignities that apes had previously endured. In one draft, Ceasar orders surgery to deprive humans of their capacity for speech, which would explain why humans can’t speak in the original film.

Dehn’s vision continued the grim and uncompromising vision of humanity that the studio defanged in the previous film in an act of artistic cowardice. Paul Dehn fell ill, and the studio sought a more optimistic vision for the fifth and final film.

The studio hired a married couple, John William Corrington and Joyce Hooper Corrington, to overhaul the script. Ceasar was changed from a dictator to a god-king of sorts. Ceasar is the Law, but he is a compassionate creature that seeks to live in harmony with humans. Ape society exists in a setting designed to evoke the Garden of Eden. Their paradise is ultimately undone by a conflict rooted in another part of biblical lore: the story of Cain and Abel.

The “climatic,” final chapter is anything but epic. I’ve screened the film twice, and I couldn’t wait for it to be over both times. It’s an exceptionally tedious movie that essentially betrays the franchise’s distinctive pessimism, ending the original Ape saga with a whimper.

Battle Begins…

Our story begins in a classroom. A human teacher stands before chimpanzee children, orangutans, and gorillas. The teacher instructs the class to copy what he’s written on the board: Ape shall never kill Ape. General Aldo, a gorilla, arrives late. Like the rest of the gorillas in class, he is a full-grown adult, learning to write alongside Ceasar’s young son, Cornelius.

As adult gorillas learn how to read and write, adult chimps and orangutans discuss light-speed travel and the possibility of bending time. There is an inequity in intellect and education that reduces the gorillas to brutes. No explanation is offered. Instead, Zira’s characterization of all Gorillas as cruel and stupid persists.

General Aldo and his gorilla cohort refuse to copy the statement, “Ape shall not kill ape.” In his refusal, Aldo tears up Cornelius’ work. Their scuffle stops when the teacher shouts, “No, Aldo! No!” Aldo flies into a rage, trashing the classroom and chasing the teacher through the village until they run into Ceasar.

Ceasar proclaims himself the Law and declares he will render judgment. He listens to Virgil, the wise organatan, describe the incident. There’s a word that humans are forbidden to speak due to its historic usage during ape enslavement, a “negative imperative” beginning with the letter N.

Like a father mediating a fight between children, Ceasar tells everyone to return to class and commands Aldo and the gorillas to clean up the trashed classroom. MacDonald, now Ceasar’s chief advisor, warns Ceasar that Aldo’s hatred isn’t confined to humans.

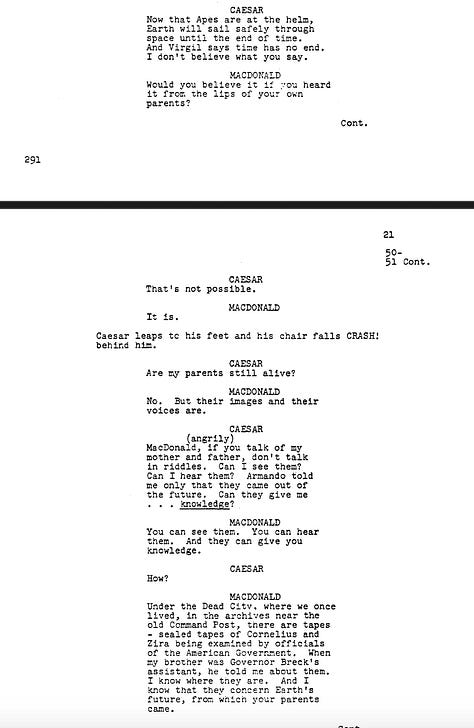

At home, Ceasar laments his lack of preparation to rule and that he never knew his parents. He wonders if they might have taught him “whether it was right to kill an evil enemy so that good can prevail.” Ultimately, Ceasar and MacDonald’s conversation ensconces the difference between the ape and human history, the core tenant of ape society that will eventually be called into question.

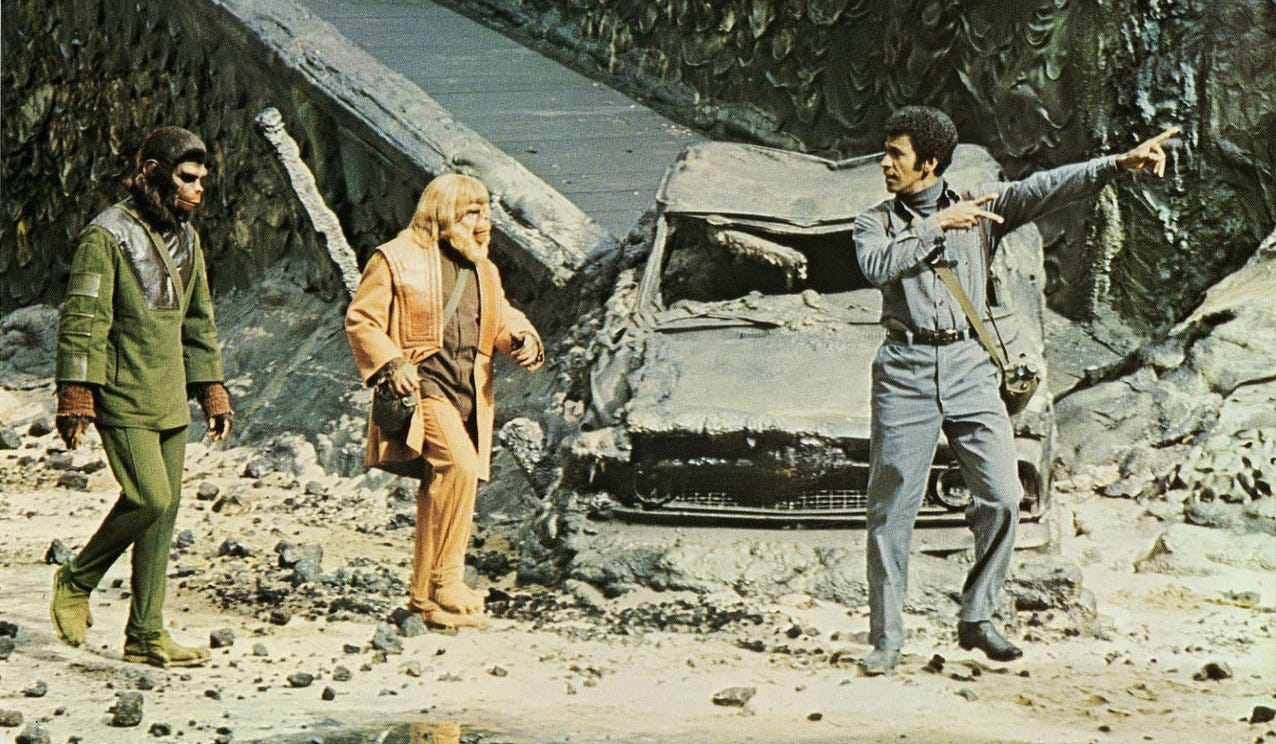

Ceasar’s optimistic view of the future is challenged by MacDonald, who informs Ceasar that his own parents foretold of the world’s destruction (as seen in Escape from the Planet of the Apes). MacDonald assures Ceasar he can see it for himself, explaining that recordings have been preserved in archives under the radioactive rubble of the ruined city. The duo seeks out Virgil and the trio and prepares for a journey into the Forbidden Zone.

Before heading out, the trio stops to arm themselves. They encounter Mandemus, the ape tasked with protecting the armory and preventing its abuse. Mandemus is the only character in the film that I care for.

He speaks with a lyrical loopiness that calls to mind Lewis Caroll’s Alice in Wonderland, in which Alice proclaims: “If I had a world of my own, everything would be nonsense. Nothing would be what it is, because everything would be what it isn't. And contrary wise, what is, it wouldn't be. And what it wouldn't be, it would. You see?”

Mandemus’ questions, however, reflect a desire to make sense of the world. He seeks to ascertain whether weapons are warranted, a serious responsibility conducted playfully:

Mandemus: What does Caesar want?

Ceasar: Weapons.

Mandemus: For what purpose?

Virgil: For self-protection in the pursuit of knowledge.

Mandemus: Self-protection against whom or what?

Virgil: We don't know

Mandemus: Well, then what is the point of protecting yourself against a danger of which you have no knowledge in pursuit of a knowledge you do not possess?

MacDonald: Oh, God.

Mandemus: Is it a knowledge for good or evil?

Virgil: All knowledge is for good. Only the use to which you put it can be good or evil

Ceasar: The sun is rising. I should like to get this matter settled before it sets.

Mandemus: Caesar has appointed me not only as the keeper of this armory but as the keeper of his own conscience. That is why I have asked six boring questions and now propose to ask a seventh before issuing or not issuing the weapons you require. What is the nature of the knowledge you cannot seek without weapons?

MacDonald: The knowledge of Earth's ultimate fate, recorded on tapes in the archives of the forbidden city.

Ceasar: Which is contaminated but still may be inhabited by humans.

Mandemus: Come in.

Mandemus’ questions remind heroes and audiences alike of the complicated nature of the quest for knowledge. He poses questions that refute the pursuit of knowledge for knowledge’s sake, especially if violence is part of the process. Mandemus’ skepticism isn’t exclusive to the realm of science.

As our characters arm themselves, Mandemus waxes philosophical about religion and the logical failings of a belief system that claims to know the future and operates beyond the capacity for reason. He says what may be my favorite line in the whole series:

“Oh. I really don't hold with knowing the future. Even my own, which is short… I mean, if we knew for a fact there was an afterlife, and that the afterlife was bliss eternal, we'd all commit suicide in order to be able to enjoy it.”

-Mandemus, telling it like it is

As they near the ruined city, their equipment shows high radiation levels. Virgil warns that if they linger too long, they will change and “become inmates.”

Their entry into the ruined city alerts Governor Kolp, the leader of the surviving humans, has taken Breck’s place. Once the intelligent investigator whose rigorous questioning led to Armondo’s suicide by defenestration, Kolp has devolved over the intervening twelve years into a complete dunce.

Kolp is becoming a mutant, but for some reason, the radiation is making humans stupider before humanity’s intelligence would eventually rebound, granting them the power of telepathy and visual projection, as seen in Beneath the Planet of the Apes,

At this stage in Ape history, Kolp is a caricature of humanity’s most idiotic impulses. He is bored by the peace that has endured since the city’s destruction. Observing our protagonists via security camera, he readies his troops for violent confrontation.

In the archives, Ceasar and friends watch clips from Escape from the Planet of the Apes. Ceasar’s parents, Zira and Cornelius, explain the war between humans and gorillas that results in the nuclear annihilation of the entire planet, as seen in Beneath the Planet of the Apes.

Ceasar suddenly understands why humanity has been so hostile and had sought his abortion in Escape from the Planet of the Apes. He is the link to a terrible future. Virgil, who has previously theorized about travel through time and space, posits that avoiding the apocalypse awaiting Earth around the year 3950 may be possible. Ceasar resolves to do all he can.

The mutants attack, causing Ceasar and friends to turn tail and run. Kolp is advised that, although armed, all signs indicate that Ceasar came on a mission of peaceful exploration. Kolp’s paranoia and bloodlust lead him to ignore his advisors. He sends scouts to follow Ceasar back to the Ape village. Kolp also seeks to avoid a grim future for humanity but is determined to use violence and eradicate all intelligent apes.

Ceasar has convened an emergency council meeting in the Ape village to share his findings about the surviving humans. Aldo seeks to form an army to crush the humans. Ceasar forbids it. He explains that the radiation of the Forbidden City would mutate Aldo and all his children. Instead, Ceasar opts to increase defenses, hoping that the humans will leave the apes in peace. He brings MacDonald to share his insights, but Aldo refuses to allow humans to participate in the ape council. He and his fellow gorillas exit in protest.

Viewers of the series will note that Aldo’s plan is identical to that of General Ursus in Beneath the Planet of the Apes, whose armed incursion into the Forbidden City results in the detonation of the Alpha Omega bomb and the entire Earth with it.

Underground, Kolp plans a preemptive strike against the apes. Fancying himself the savior of humanity, he creates a backup plan in the event of his failure. A warhead will be launched if Kolp fails. His signal to detonate is “Alpha Omega.” It’s unclear if he’s referring to the same weapon the mutants worship in Beneath the Planet of the Apes, but it’s a definite reference to the cyclical, possibly pre-ordained end of the world.

That night, Cornelius overhears Aldo and the gorillas plotting to seize power by seizing guns. With guns, they will “smash all humans, and then Ceasar.” A rustle in the tree alerts the gorillas that Cornelius is watching.

Aldo and the gorillas flee into the night.

The following day, Ceasar visits the scene of the crime. In his innocence, he assumes his son was injured searching for his lost squirrel. MacDonald, wise to the dark nature of man and ape, searches the scene more closely. He notes that the branch didn’t break naturally but was cut with a blade.

Back in Ceasar’s home, the doctor informs Cornelius’ mother, Lisa, that the prognosis is terminal. Lisa does not tell Ceasar because “he still believes he can change the future.” Virgil speaks to MacDonald, shares the terminal prognosis, and asks how a benevolent god could allow a tree limb to break and harm an innocent child. MacDonald informs Virgil that it didn’t break; it was cut.

At that precise moment, Aldo summons the council and alerts them of the approaching human threat. He commands that apes prepare for combat and that all humans be locked in the corral. Aldo declares martial law and raids the armory.

Virgil visits Ceasar in his home and informs him that Aldo has seized power. Ceasar is apathetic. “We’ll settle that later,” he says. Virgil tells him all humans are being corralled. Ceaser refuses to leave Cornelius’ bedside as fragile peace descends into chaos. “My son needs me,” he says. “Every ape needs you right now,” Virgil replies.

Perhaps Ceasar would’ve been more attentive to Aldo’s powerplay if he knew there was no hope for Cornelius to recover. Ceasar is wasting his time because everyone has decided it’s better not to tell the truth. As a result, Ceasar is dithering at home during the crisis.

Cornelius speaks his final words, telling his father that “they hurt me” and warning him, “They want to hurt you.” Ceasar asks if Cornelius is talking about the humans. No, Cornelius replies before dying.

As armed gorillas corral humans, Ceasar wonders who could have possibly wanted to hurt Cornelius. This moment reveals Ceasar to be an absolute fool.

Is Ceasar so naive that he can’t deduce that Aldo, currently the leader of an armed rebellion, might have had something to do with his son’s injury? It would seem so. Are naivete and idiocy one and the same? Once again, it would seem so.

He commands Aldo to release the humans. At that moment, the mutant humans fire the first shot, blowing up a treehouse. Aldo and the gorillas charge toward their attackers. With twenty minutes left in the film, the battle for the planet of the apes has begun.

Most of the “epic battle” occurs in a nondescript field. Kolp’s army consists of approximately five mortars, twenty men, an old sedan, a jeep with a mounted machine gun, and a school bus. It’s a rather pathetic showing for humanity.

Amid mortar fire, the apes throw together a makeshift barricade. Apes and humans shoot at each other. Footage of the exploding treehouse is reused throughout the sequence, shot from different angles, to save money on pyrotechnics. After a few minutes of painfully uncompelling action, the barricade catches fire, and Ceasar orders his apes to retreat to the village.

The climatic clash is possibly the dullest sequence in an already underwhelming film. Budgetary restraints make the conflict feel small, and reusing shots makes the sequence feel repetitive. Yet it drags on for minutes because this measly display of spectacle was, in theory, worth the price of admission.

The action isn’t attached to any character’s perspective. Instead, the camera lingers at a distance like a neutral observer. According to the crew, the director was a “competent visionary” who didn’t need to create storyboards. They were incorrect. Director J. Lee Thompson should have storyboarded this sequence.

Kolp and his army roll into the ape village and find Ceasar moaning on the ground, surrounded by dead apes. Holding Ceasar at gunpoint, Kolp monologues about restoring human supremacy long enough for two apes to hurl explosives at Kolp’s army.

“Now, fight like apes!” Caesar shouts. The dead apes spring to life and grapple with Kolp’s forces.

The apes turn the tide of the battle. They overpower the humans, and the same shot of a net being dropped on humans is used four times in thirty seconds.

Ceasar commands his apes to capture, not kill, their attackers. Kolp and a few of his cronies return to the school bus and flee. Ceasar lets them go. However, Aldo waits over the ridge and charges the school bus, shouting, “No prisoners!” They circle the bus on horseback and kill all remaining humans with automatic weapons and explosives.

Back in the ape village, the apes hail Ceasar as their leader. He tells Virgil, “Free the humans. All of them.”

“No!” Aldo shouts as he rides up on horseback. Aldo’s refusal, his declaration of a “negative imperative,” is a historic moment in the Sacred Scrolls.

“…on a historic day commemorated by my species and fully documented in the secret scrolls, there came an Ape called Aldo, who didn't bark. He articulated. He spoke a word which had been spoken to him, time without number, by Humans. He said ‘No.’”

-Cornelius in Escape from the Planet of the Apes

This is not the liberatory moment as it was framed in the Sacred Scrolls. Rather, Aldo’s refusal is a refusal of peace and constitutes an attempt to overthrow Ceasar, the most sacred figure of the Ape religion. Aldo’s “negative imperative” comes with his command to kill all the humans and Ceasar with them.

What does this incongruity between Aldo’s actions and the actions recorded in the Sacred Scrolls reveal? Is it an example of historical revisionism? Do successive generations sanitize Aldo’s actions? Does the contradiction suggest that the future has changed, just as Virgil thought possible?

Or perhaps it reveals the film’s poorly conceived attempt to nominally check all the boxes of Cornelius’ dispatches from the future. Aldo’s historic refusal would have made far more sense in the previous installment when apes rebelled against their human masters. If framing Aldo’s historic refusal had any intent, the screenwriters fumbled it in their rush to the film’s messy conclusion. The moment feels confused, contrived, and reeks of poor writing.

Aldo refuses to relinquish power and prepares to have Ceasar executed in public. From the sidelines, Virgil says, “Ape has never killed ape, let alone an ape child.” With the (obvious) truth now in the open, Ceasar finally comprehends who killed his son. Every ape turns on Aldo, disgusted by his betrayal of the most sacred law.

As the mob turns on him, chanting, “Ape has killed ape,” Aldo climbs a tree to escape. Caesar scales the tree in pursuit. Aldo draws a blade and attempts to stab Caesar. Caesar stays Aldo’s hand, knocking him off-balance. Aldo falls from the tree and lands with a thud, dead.

“Should one murder be avenged by another?” Ceasar asks Virgil.

“Only the future can tell,” Virgil replies, “So let us start building it.”

The humans are freed from the corral. MacDonald demands humans be free to live as equals to apes. Ceasar agrees to “rebuild what’s ruined and begin again.” He asks MacDonald, “Can we make the future what we wish?”

MacDonald responds, “I’ve heard that it’s possible.”

With every weapon returned to the armory, Mandemus expresses a desire to see the armory blown up now that the danger has passed.

“The greatest danger of all is that the danger is never over,” Virgil tells Mandemus.

“So,” Caesar continues, “we must be patient and wait.”

The screen fades from Ceasar’s face to the Lawgiver, who concludes, “We still wait, my children. But as I look at apes and humans living in friendship, harmony, and peace, now, some 600 years after Caesar's death, at least we wait with hope for the future.”

A girl standing beside a young chimp asks, “Lawgiver, who knows about the future?”

“Perhaps only the dead,” The Lawgiver replies. The camera pans up and right, settling on a statue built in Ceasar’s honor.

The camera zooms in, and a single miraculous tear runs down the statue’s cheek.

The end.

Making Sense of Nonsense

So concludes the Planet of the Apes saga.

According to screenwriters and scholars, the ending suggested that things were moving in a hopeful direction. In 1973, the Vietnam War was winding down. America was exhausted by a decade of political violence. Battle of the Planet of the Apes purports to channel the national exhaustion and desire for hope.

Whether that desire for hope was genuine or not, history has shown that there has been no turn towards redemption. Humanity’s situation is as dire as ever, and, as a result, Battle for the Planet of the Apes feels phony, especially considered alongside the rest of the franchise.

Ending on a hopeful note strikes the wrong cord for a series defined by nihilism and despair. The final film reduces the series’ ethos to nonsense in which, as Alice says, “Nothing would be what it is, because everything would be what it isn't. And contrary wise, what is, it wouldn't be. And what it wouldn't be, it would.”

The series would be adapted for television. The Planet of the Apes would be relegated to the small screen for 28 years until director Tim Burton returned it to the big screen, designed for the new millennium: devoid of soul and chock full of nonsense!

Until next week, don’t forget murder is wrong, my dear film freaks.