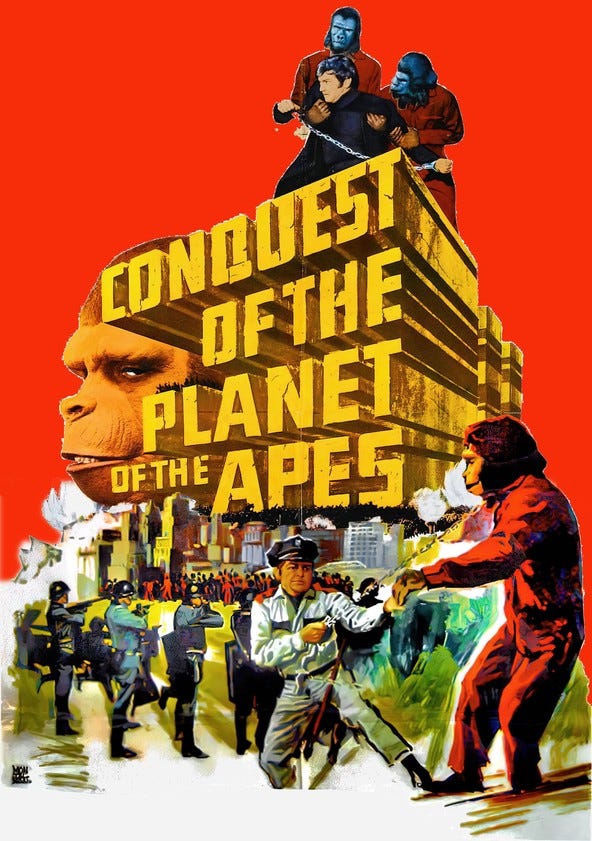

Conquest of the Planet of the Apes ⭐️⭐️ 1/2

Released in 1972, Conquest of the Planet of the Apes is by far the most upfront about its sociopolitical subtext. As discussed in part one of this Planet of the Apes Retrospective, the series has most readily been interpreted as a racial allegory. Here, subtext essentially becomes text. This is a film that directly engages with issues of race and civil unrest in America circa 1972.

Amid a background of unrest and fear, Conquest of the Planet of the Apes turns to genre fiction in an attempt to explore contemporary issues of racial oppression and, ostensibly, cultivate empathy and understanding. Once again, it abstracts and recontextualizes societal issues by situating them within a future populated by intelligent apes. The film expresses sympathy for the oppressed and frames violent rebellion as the inevitable result of authoritarian repression. Yet, for all the sympathy the film espouses, there are still prominent displays of moral equivocation that seek to appease the white audience’s discomfort.

Two cuts of the film exist: the theatrical and the “unrated” cut. Both were included on my Blu-ray copy, so I screened them both. They are functionally identical until the final scene, which is substantively changed in ways that reveal the economic and systemic factors that underlie the film’s production.

Conquest’s Political and Industry Context

Amid the Civil Rights Movement, Americans had witnessed police brutalize peaceful protestors. Following the 1963 bombing of a Black church in Birmingham, Alabama, that killed four girls, the strategy of nonviolent resistance espoused by Martin Luther King Jr. was met with an opposing, more militant school of thought that regarded political violence as a necessary part of catalyzing change.

This led to the creation of The Black Panther Party, which sought to arm Black Americans and empower them to protect their communities from the police. Building a better society required disrupting the status quo, but the powers that be were not listening. If non-violence was going to be met with firehoses and police dogs, then revolt must become a viable tool to dismantle systems of violent oppression.

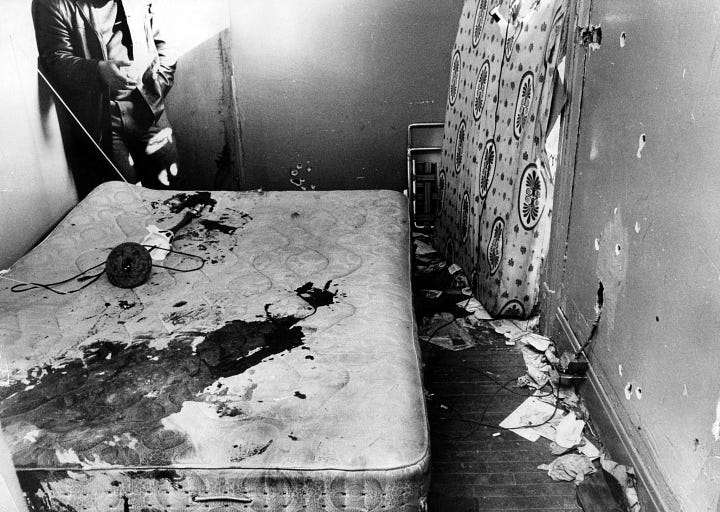

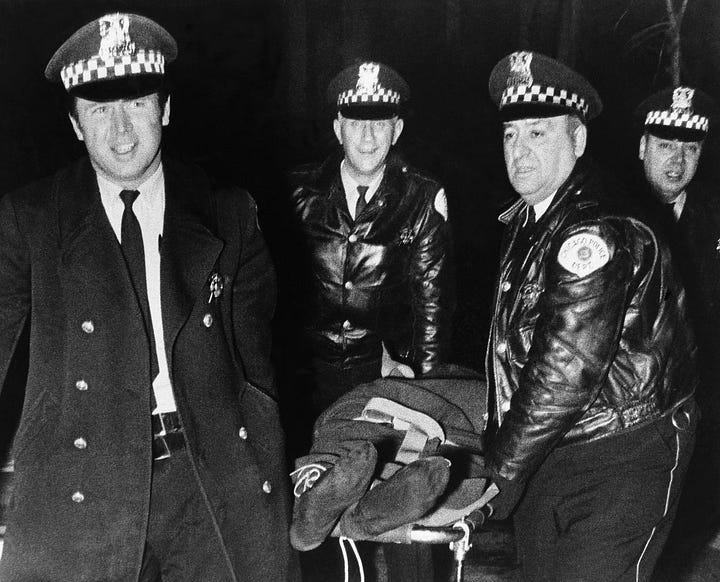

In response, “law enforcement” in cities like Chicago conducted political assassinations of Civil Rights activists such as Fred Hampton, Chairman of the Illinois Black Panther Party. State violence, carried out by local and federal agents in cities across America, led to the explosion of “race riots” in cities across the country. White Americans watched civil unrest erupt on their televisions, and politicians capitalized on fear and division to gain power.

Conquest of the Planet of the Apes was also released during the Blaxploitation boom, a period in the 1970s during which black filmmakers produced films for black audiences outside the studio system. Hollywood studios never catered to Black audiences. Their experiences were not reflected on the big screen. Historically, Hollywood’s inclusion of Black characters in studio films was mired in racist stereotypes, an ugly history of blackface, and a dehumanizing treatment of Black talent in musicals and beyond.

The history of the Blaxploitation genre and its enduring legacy is as complicated as it is fascinating. If you want to learn more, pick up a copy of Odie Henderson’s incisive and informative book, Black Ceasars and Foxy Cleopatras: A History of Blaxploitation Cinema.

So, in rudimentary terms, Blaxploitation cinema refers to films made by Black artists to reflect the Black experience for Black audiences and, crucially, allows the protagonist to triumph over racist white villains that represent systemic violence, oppression, and exploitation.

By contrast, Conquest of the Planet of the Apes is a film concerned with the plight of Black Americans, made by and for white people. For all of its noble intentions, the film’s desire to confront racist oppression and violent resistance would ultimately be negated by financial considerations. The film’s ending would be altered, guided by artistic cowardice in the face of white fragility. The film’s ending is the most compelling since the original, or the most disappointing, depending on which cut of the film you see.

1991: Authoritarian Dystopia

Conquest of the Planet of the Apes takes place twenty years after the events of Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971). Production had saved a lot of money by setting the previous installment in contemporary America. For this installment, the studio avoided constructing sets by shooting their film in Century City, a portion of the studio backlot sold to real estate developers amid 20 Century Studio’s economic troubles. The modern, brutalist architecture comports well with the film’s dystopian conception of North America in 1991.

The film begins with the duo entering a city via helicopter. Armondo warns Milo that the city is different and that humans would fear Milo’s ability to speak, so Milo must pretend to blend in. The city is heavily policed by officers of an authoritarian state that harasses apes with near impunity.

Armondo explains recent events to Milo and, by proxy, the audience. A virus, inadvertently brought to earth by the ape-onauts of the previous film, killed every cat and dog by 1983.

Things are progressing precisely as Cornelius, Milo’s father, explained to Dr. Hasslein in the previous film.

“It began, in our prehistory, with the plague that fell upon dogs and cats. Hundreds and thousands of them died, and hundreds and thousands had to be destroyed to prevent the spread of the infection.

By the time the plague was contained, Man was without pets, and for Man, this was intolerable. He might kill his brother, but he could not kill his dog. So, Humans took primitive Apes as pets.

They were quartered in cages, but they lived and moved freely in human houses. They became responsive to human speech and, in only two centuries, progressed from performing mere tricks to performing services.

They became alert to the concept of slavery and, as their numbers grew, to slavery's antidote, which is unity. They began to assemble in small bands. They learned the art of corporate and militant action. They learned to refuse.”

-Cornelius, explaining the rise of Apes.

Shortly after their arrival, the authorities seek to question Armondo. He agrees to be questioned. Armondo is confident it won’t take long and assures Milo that he will return shortly. Armondo, always the optimist, has too much faith in his fellow man. He is surprised when he is treated with hostility in police custody. Governor Breck (Don Murray) grills Armondo about the possibility that Zira’s baby is still alive. Armondo refutes the charges, but Breck remains unconvinced.

Breck harps on the rising incidences of ape disobedience to convey the seriousness of the situation. The governor’s top advisor, Malcolm MacDonald (Hari Rhodes), argues that Governor Breck is overstating the severity of the issue and claims that a recent incident of an ape killing his master was the result of sustained physical abuse and lashings. The fact that MacDonald is a black man is not a coincidence, nor is the caucasian Breck’s vitriolic reply that the ape deserved whatever violence was inflicted by its master.

Without Armondo, Milo is left to wander in a hostile environment. As day turns to night, Milo sneaks into a cage of orangutans that, unbeknownst to him, are headed for “Ape Management.”

In Ape Management, apes are sorted by race and trained to be “more civilized.” They are taught to wash their hands and pour water for their masters. Their human “reeducators” only speak two words to the apes: “Do!” and “No!”

Conquest’s visuals lack subtlety but not intention. The way Milo is treated evokes the history of slavery in the United States. Shortly after being placed into Ape Management, Milo is selected as a “superior male.” His intelligence does not go unnoticed, as he silently excels at the tasks he is given. As a result, he is selected to inseminate a female chimp to breed a superior generation of servile apes. Unbeknownst to his overlords, forced breeding allows Milo to pass along his genetic capacity for speech.

Shortly thereafter, Milo is brought to a slave auction. His shackles fall to the ground as he is put up for auction. To the surprise and delight of his prospective masters, Milo recuffs himself. His seemingly servile temperament causes a bidding war. Ultimately, Governor Breck purchases Milo to act as a bartender.

Back in Breck’s office, Milo is told to choose his new name from a book. Milo points to Ceasar, a king’s name. Breck is made uncomfortable and decides Milo isn’t suited to be a bartender. He is reassigned to the command center.

Meanwhile, Armondo is being subjected to Conquest’s version of a tribunal: a closed-door interrogation that includes torture. Finding himself a victim of the regime’s brutal and covert “justice system,” Armondo commits suicide by defenestration rather than betraying Milo’s identity.

Ceasar, the ape formerly known as Milo, overhears Breck discussing Armondo’s suicide. The death of his friend at the hands of his new human overlords radicalizes Ceasar. His grief turns to rage, and he organizes an ape rebellion seemingly overnight.

Ceasar recruits his fellow apes and encourages them to rebel. This is by far the film’s weakest sequence. The filmmakers clearly had no idea how to cinematically depict the mounting rebellion, and the visual shorthand it employs is comically inept. Ceasar cannot speak with his fellow apes, so he recruits them by staring at them from a distance. It’s supremely strange and entirely inadequate visual shorthand.

Despite the film’s embarrassing cinematic shortcomings, Ceasar’s rebellion has begun. As Ceasar builds his army, government agents uncover the inconsistencies surrounding Ceasar’s arrival. They note that he was the only chimp to arrive in a cage of orangutans and that chimps are not native to where they were captured.

It turns out the anomalous chimp they’ve been searching for was purchased by Governor Breck at auction. Breck contacts MacDonald in the command center and commands him to find Ceasar. MacDonald finds Ceasar but, skeptical of Breck, doesn’t immediately turn him in. Instead, MacDonald attempts to communicate with Ceasar. Heartened by MacDonald’s sympathy, Ceasar entrusts MacDonald enough to reply verbally. Their exchange begins a dialogue about violent revolution being the only way to secure freedom and effectuate change.

MacDonald: I wish there were some way we could communicate, so you’d understand—

Ceasar: I understand, Mr. Macdonald… Yes, I’m the one they’re looking for.

MacDonald: I never believed it. I thought you were a myth.

Ceasar: I’m not. But I’ll tell you something that is: the belief that humans are kind.

MacDonald: Ceasar, there are some—

Ceasar: A handful, but not most of them. They won’t be kind until we force them to. And we can’t do that until we’re free.

MacDonald: How do you propose to gain this freedom?

Caesar: By the only means left to us. Revolution.

MacDonald: But it's doomed to failure!

Caesar: Perhaps. This time.

MacDonald: And the next.

Caesar: Maybe.

MacDonald: And you'll keep trying?

Caesar: You, above everyone else, should understand that we cannot be free until we have power! How else can we achieve it?

Ceasar’s appeal to MacDonald, that “[he] above everyone else” should understand, directly appeals to MacDonald’s identity as a Black American. It is an appeal to history that seeks to cultivate empathy on the basis of allegorically comparable oppression. In this exchange, subtext becomes text, reflecting the film’s desire to make the boldest statement in the franchise to date.

MacDonald allows Ceasar to escape, but Ceasar is immediately apprehended. Short, uneventful games of cat-and-mouse such as this appear throughout the franchise. In Breck’s custody, Ceasar is strapped to an electric table and tortured until he speaks. Ceaser suffers and finally breaks, confirming Breck’s suspicions by uttering two words: “Have… mercy.”

Breck, now certain he’s apprehended the hyper-intelligent ape, pushes to have Ceasar executed on the electric table. Meanwhile, MacDonald heeds Ceasar’s plea. He slips away, enters Central Power Control, and disables the electric shock table. Ceasar pretends to be electrocuted, and Breck, satisfied, exits the room. Ceasar garrotes the remaining guard and escapes to the Ape Rebellion’s headquarters.

Ceasar and his guerilla army flood the streets. They clash with riot police as they make their way to Ape Management to free all the other apes and rally them to their cause.

The violent struggle that ensues includes imagery of whips, a reference to the brutal abuse inflicted during chattel slavery. Meanwhile, the confrontations with riot police parallel the horrors of slavery with the contemporary forms of violent oppression by the State that led to race riots. Screenwriter Paul Dehn sought to evoke images Americans had seen in their homes, on their small black and white televisions, and render them in color on the big screen.

Ceasar and his army breach the command center and find Governor Breck. They force him to his knees and, with the power dynamics inverted, Ceasar asks him a question:

Ceasar: Tell me, Breck, before you die, how do we differ from the dogs and cats you and your kind used to love? Why did you turn us from pets into slaves?

Governor Breck: Because your kind were once our ancestors. Man was born of the ape, and there's still an ape curled up inside of every man — the beast that must be whipped into submission, the savage that has to be shackled in chains. You are that beast, Caesar. You taint us. You poison our guts! When we hate you, we're... we're hating the dark side of ourselves.

With that, Breck is dragged into the street for public execution, a true dictator’s demise a la Benito Mussolini or Muammar Gadhafi. MacDonald objects before Breck is executed:

MacDonald: Caesar... Caesar! This is not how it was meant to be.

Caesar: In your view or mine?

MacDonald: Violence prolongs hate, hate prolongs violence. By what right are you spilling blood?

Caesar: By the slave's right to punish his persecutor.

MacDonald: I, a descendant of slaves, am asking you to show humanity.

Caesar: But, I was not born human.

MacDonald: I know. The child of the evolved apes.

Caesar: Whose children shall rule the earth.

MacDonald: For better or for worse?

Caesar: Do you think it could be worse?

MacDonald: Do you think this riot will win freedom for all your people? By tomorrow—

Caesar: By tomorrow it will be too late. Why a tiny, mindless insect like the emperor moth can communicate with another over a distance of 80 miles—

MacDonald: An emperor ape might do slightly better?

Caesar: Slightly? What you have seen here today, apes on the five continents will be imitating tomorrow.

MacDonald: With knives against guns? With kerosene cans against flamethrowers?

Caesar: Where there is fire, there is smoke. And in that smoke, from this day forward, my people will crouch and conspire and plot and plan for the inevitable day of Man's downfall - the day when he finally and self-destructively turns his weapons against his own kind. The day of the writing in the sky, when your cities lie buried under radioactive rubble! When the sea is a dead sea, and the land is a wasteland out of which I will lead my people from their captivity! And we will build our own cities in which there will be no place for humans except to serve our ends! And we shall found our own armies, our own religion, our own dynasty! And that day is upon you now!

These are the final words of the film’s original, unrated cut. MacDonald and Ceasar’s exchange touches upon the philosophical schism within the Civil Rights movement. It is a dark ending that articulates the necessity of violent revolt to create a better society akin to the perspective of the Black Panther Party. As an enslaved ape, Ceasar is understandably unconcerned with the well-being of his former masters. He is a leader committed to uplifting his own community. If building a better world comes at the expense of humanity’s well-being, so be it. He is warned of the dangers he will face, but he is undaunted. Ceasar has started a liberation movement, and the fires of rebellion will continue to spread. The oppressor class should be afraid. Their day of reckoning has come.

Paul Dehn’s grim vision was approved by the studio and comports with the Planet of the Apes franchise’s distinctive pessimism. However, parents walked out with their children during a test screening in Phoenix, Arizona. The film was apparently too intense. The studio worried they would be given an R-rating, severely impacting their appeal at the box office. Despite having no money for reshoots, the studio resolved to re-edit the movie, remove the most violent parts, and add a coda to Ceasar’s speech that would negate the film’s ethos.

Ceasar’s original speech remains in the film's theatrical release, but Roddy McDowall recorded additional lines in post-production. There was no footage of Ceasar saying the new lines, so the lines are delivered over repurposed footage. The camera shoots Ceasar in a close-up; his lips are never seen. Perhaps it is because Ceasar is talking out of his ass when he says:

Caesar: But now... now we will put away our hatred. Now we will put down our weapons. We have passed through the Night of the Fires. And who were our masters are now our servants. And we, who are not human, can afford to be humane. Destiny is the will of God. And, if it is man's destiny to be dominated, it is God's will that he be dominated with compassion and understanding. So, cast out your vengeance. Tonight, we have seen the birth of the Planet of the Apes!

Breck is no longer executed. The footage of apes raising their weapons was reversed, making it appear that the apes were lowering their weapons. It’s a slapdash ending that, on a technical level, is so poorly done that it’s embarrassing to watch.

Thematically, it feels like a betrayal. The text is muddled beyond salvation, with theatrical viewers left to square: “From this day forward, my people will crouch and conspire and plot and plan for the inevitable day of Man's downfall… there will be no place for humans except to serve our ends!” with “Now we will put down our weapons. We have passed through the Night of the Fires.”

Is this the beginning of a revolution or the end? These contradictory sentiments, spoken within moments of each other, suggest that the violent revolution we witnessed is over. Now comes “domination with compassion,” which sounds uncomfortably similar to “separate but equal” and other rhetorical platitudes used to perpetuate white supremacy.

It’s a genuine shame that Conquest of the Planet of the Apes, the boldest film in the franchise, was butchered to preserve the studio’s economic status quo. The desire to make a profitable movie that wouldn’t make white audiences uncomfortable proved more important than creating art with a message.

More than any other installment, Conquest of the Planet of the Apes showcases the science fiction genre’s ability to directly reflect real-world issues in ways that promote critical thought. Simultaneously, it is a display of artistic cowardice that exemplifies the industry’s limited willingness to engage with the genre’s capacity to make audiences uncomfortable.

The magnanimity that Ceasar espouses at the end of the theatrical cut is consistent with his characterization in the following, final (and worst) film of the original franchise, Battle for the Planet of the Apes (1973), which dabbles in the inoffensive realm of faith-based allegory rather than engage with the generic elements of science fiction.

Until next week, film freak.