Planet of the Apes Retrospective - Part VII

Rise (2011), Dawn (2014), War (2017), and Kingdom (2024)

Rise of the Dawn of the War for the Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes

Ten years after the critical failure of Tim Burton’s Planet of the Apes (2001), Apes would return to the big screen again. This time, however, they would look quite different.

Advancements in computer-generated effects enabled filmmakers to render realistic, expressive apes via motion capture. Sensors placed on the actor’s face allow visual effects artists to map the actor’s movement style and facial details onto three-dimensional virtual models. The results are visually astounding, facilitating a level of immersion that was hitherto impossible for the Planet of the Apes franchise.

For many reasons, including contemporary visual effects, contemporary Planet of the Apes films are the definitive viewing experience. The first three films of the tetralogy, Rise, Dawn, and War, focus on Ceasar.

Over the course of three films, Serkis’ Caesar evolves to meet the challenges of a changing world. Unlike Roddy McDowall’s conflicted portrayal of the character, Caesar is not a violent revolutionary as depicted in — but ultimately negated in the theatrical cut of — Conquest of the Planet of the Apes. Nor is he the god-king paragon of altruism and tolerance from Battle for the Planet of the Apes.

The ethical and philosophical questions that Ceasar faces are far more nuanced than in previous installments (e.g., Beneath the Planet of the Apes), and as Caesar changes the world, the world changes him.

He consistently strives to do what’s right as a leader, but things are rarely black and white. Instead, he’s a fallible character operating in a world of grey. Unlike Burton’s Planet of the Apes, the contemporary tetralogy reengages with the sci-fi genre to explore substantive themes on par with the original Planet of the Apes (1968).

If this retrospective has piqued your interest, but you don’t want to watch the entire Apes franchise, I believe Rise, Dawn, War, and (to a lesser extent) Kingdom are the ones to watch.

To not spoil your viewing experience, I intend to be less comprehensive in my discussion of contemporary films. Spoilers will follow, primarily focusing on relevant themes and not divulging the specifics of the plot.

As of publication, the Planet of the Apes Franchise is available to stream on Hulu/Disney+, except Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes, which is currently in theaters.

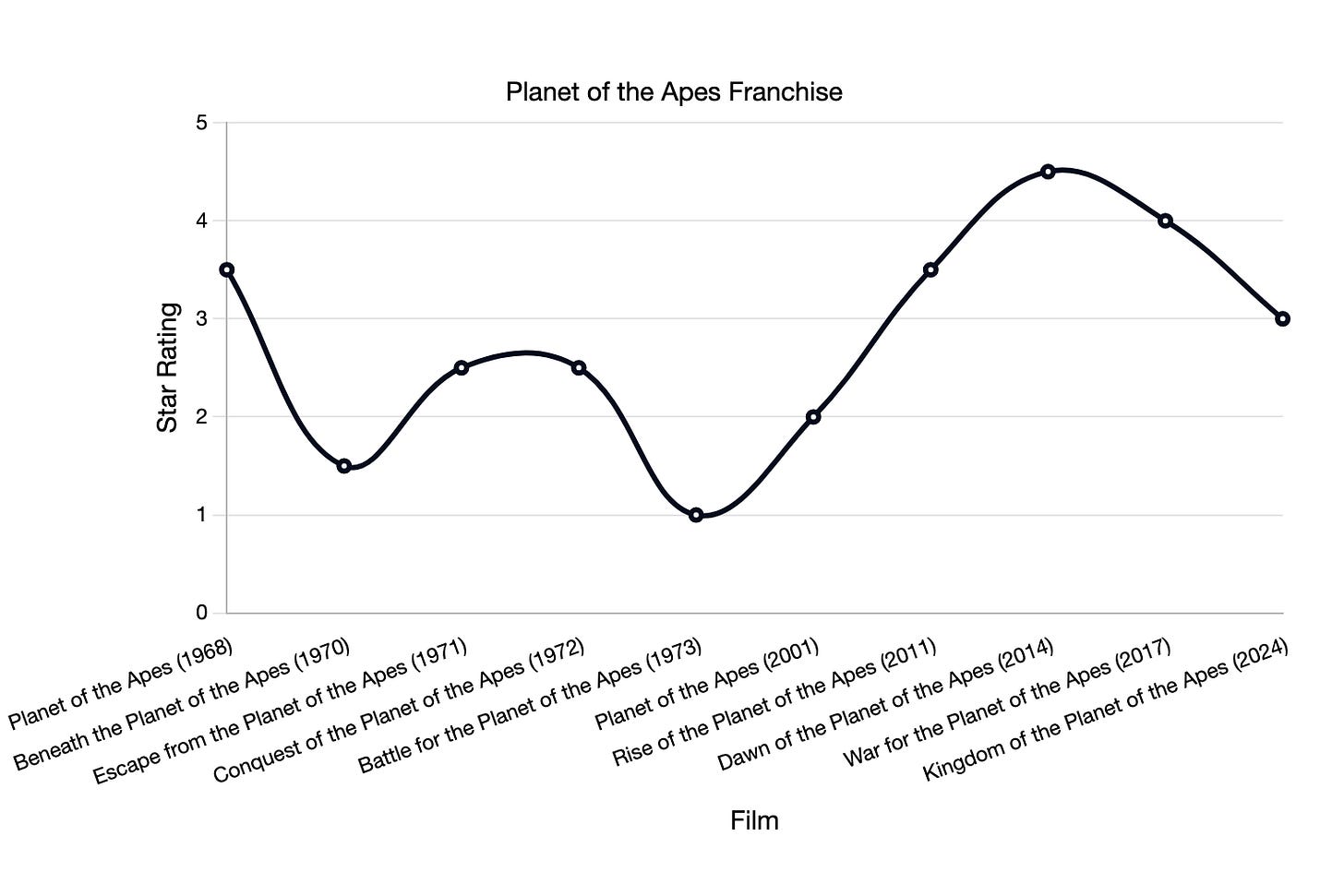

Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011) ⭐️⭐️⭐️1/2

Rise of the Planet of the Apes is a solid foundation that successive films build upon. As the first film in the contemporary run, it prominently features a human surrogate for audience identification. James Franco plays Will Rodman, a pharmaceutical chemist working to develop a cure for Alzheimer’s. Working for the company Gen-Sys, he develops a virus-based therapeutic, ALZ-112.

His initial tests on a female chimpanzee called Bright-Eyes (a reference to Zira’s nickname for Taylor in Planet of the Apes (1968)) are a success, with notable increases in cognitive capacity. Flecks of green also appear in the test subject’s irises, an unwanted secondary side effect.

At the film's beginning, Will is eager to progress to clinical trials on human patients. However, a violent incident in the lab causes the board to withdraw their support for the project. Will’s research is terminated, and his simian test subjects must be put down. Will cannot bring himself to kill Bright-Eye’s newborn and, instead, furtively brings the ape home.

Heartened by Ceasar’s rapid intellectual development, Will hopes that the ALZ-112 may still be a viable treatment for his father (John Lithgow), who has Alzheimer’s. In violation of FDA guidelines, Will administers the ALZ-112 to his father, Charles.

Despite his good intentions, Will’s actions are ethically dubious. At work, his simian test subjects are unwilling participants, provoking ethical questions surrounding animal testing. Similarly, Will's decision to administer an experimental drug to his father with late-stage Alzheimers lacks consent.

Will’s intentions are framed as noble, but that doesn’t negate the fact that Will is, in essence, playing God. At first, Will’s father appears to be improving, but eventually, ALZ-112 becomes ineffective in staving off his father’s cognitive decline. All the while, Caesar’s cognitive capacity continues to increase.

As Caesar grows from infant to adolescent, he develops a deep love for Will and Charles. They provide a loving home, demonstrating humanity’s capacity for kindness to Caesar. However, as Caesar becomes increasingly sentient, he begins to question his place in Will’s family. Is he family or a family pet?

Caesar’s protective instincts cause him to attack a neighbor, an incident likely inspired by the 2009 pet chimpanzee attack in Stamford, CT, that left a woman faceless. As a result, Will is forced to relocate Caesar to “The Ranch,” an animal sanctuary run by Mr. Landon (Brian Cox), who promises a friendly and enriching environment where Caesar can be with his own kind.

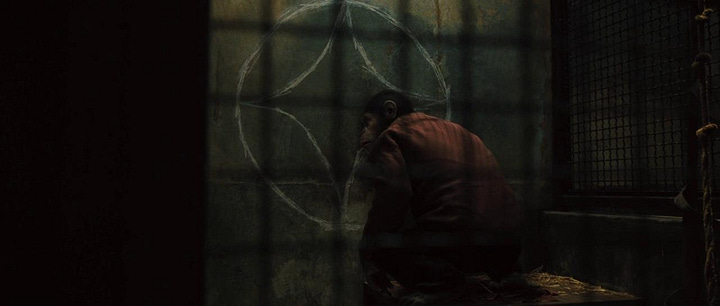

Caesar’s banishment is not Will’s decision; it’s court-ordered. Despite Will’s promises to return, Caesar experiences abandonment and betrayal by the human he trusted most. The Ranch proves to be more like a prison than a sanctuary.

Subtextually, Caesar’s non-consensual relocation to The Ranch parallels the relocation of elders into nursing homes, which often promise enriching environments for aging loved ones unable to live at home safely but are, in fact, hotbeds of neglect and elder abuse. Rise of the Planet of the Apes mirrors our culture’s casual disregard for the rights and well-being of the most vulnerable members of the “traditional family.” There is a subtextual suggestion that the culturally accepted banishment of elders deemed incapable of living alone is, in some way, subhuman.

Considered within this context, Will’s unethical determination to continue developing a cure for his father’s Alzheimer’s may be interpreted as a noble rejection of societal norms. The failure of ALZ-112 leads Will to develop ALZ-113, a “more aggressive” strain of the therapeutic virus that, he hopes, will continue to help his father.

Nevertheless, Will’s scientific pursuits force him to abandon Caesar, leaving him in a hostile environment. Caesar is cohabitating with apes for the first time in his life. His socialization within human society has left him unprepared for the challenges of intra-ape social dynamics.

At the Ranch, Caesar’s intellect is both a blessing and a curse. It separates him from his fellow apes but also allows him to understand and ascend the hierarchy more effectively. He is smart enough to know that he is stuck in an abusive environment and clever enough to plan an escape and organize an uprising.

In a pivotal scene, a human oppressor says the most iconic line from the original 1968 film, “Get your stinking paws off me, you damn dirty ape!” In Rise, Caesar replies, “NO!” It is a significant moment in Ape lore, first mentioned by Cornelius on Escape from the Planet of the Apes and later depicted in Battle for the Planet of the Apes. Where Battle botched the depiction of “Ape’s first refusal,” Rise understands the supreme significance of this moment. It indicates a deep understanding of the source material and showcases the contemporary tetraology’s capacity to use pieces of the original franchise to create something more meaningful.

The Rise of the Planet of the Apes marks the beginning of humanity’s downfall. As the credits roll, a map shows the ALZ-113 virus that Will created in a lab begin to spread across the globe.

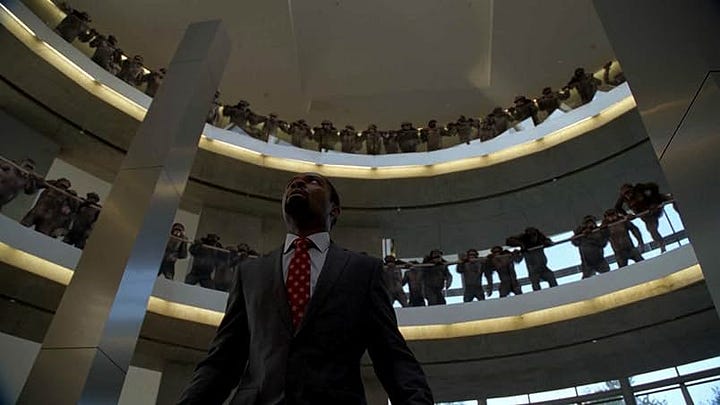

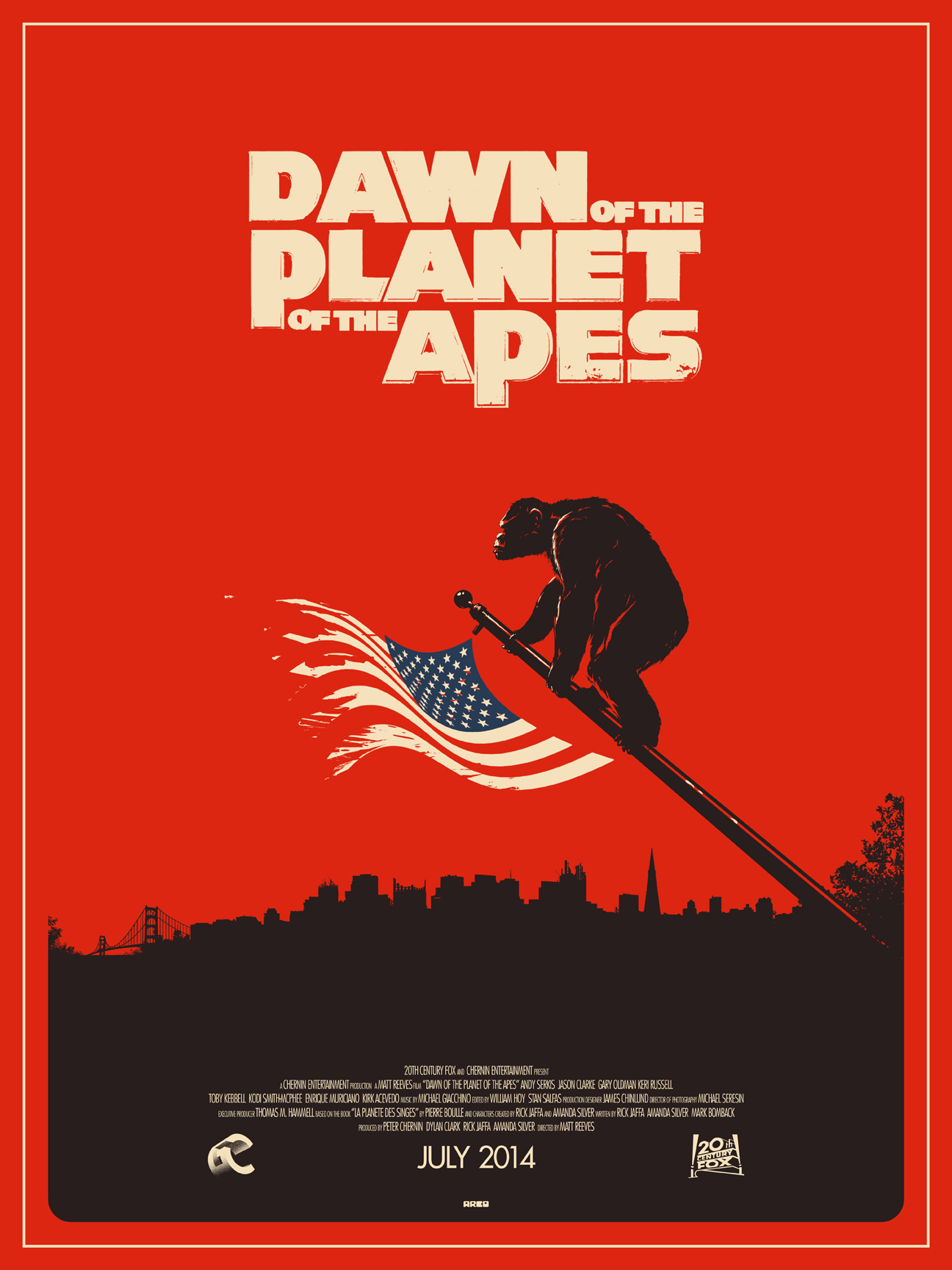

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014) ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️1/2

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes does everything a Planet of the Apes film would ever want to do, and it does it beautifully. For my money, it is the pinnacle of the Planet of the Apes franchise.

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes begins with one of the most compelling opening sequences I can recall. Viewers are brought up to speed in a two-minute sequence that, upon the film’s release in 2014, plays off paranoia surrounding the 2009 Swine Flu Pandemic (H1N1 virus) and the largest recorded outbreak of Ebola in western Africa beginning in 2013.

Ten years after Dawn’s release, the global trauma of the COVID-19 pandemic lends the film’s opening heightened prescience and horror. The sequence, linked below, is an exemplary showcase of the sci-fi and horror genre’s unique capacity to reflect our collective fears in a way that, in retrospect, feels eerily predictive.

The masterful, must-watch opening to Dawn of the Planet of the Apes:

Beginning twelve years after the events of Rise, ape society is starting to advance meaningfully. They’ve built a village, led by Caesar, flourishing in the forest.

The apes haven’t encountered humans for two years, so when a group of humans trespass in the forest, it sends shockwaves through their community. An adolescent ape stumbles upon an unsuspecting human, and the frightened human fires a gun, wounding the young ape. Caesar and his fellow apes arrive at the scene and demand the humans leave.

The humans return to their outpost, a city now in shambles, and inform their leader, Dreyfus (Gary Oldman), of their encounter with the apes and inability to complete their task: restoring a dilapidated hydroelectric dam. The human settlement is running low on fuel. To maintain peace within their community, they need “power.” Until then, Dreyfus wants to keep the Ape encounter secret to avoid causing panic.

When Dreyfus speaks about power, he refers to electricity, but “power” can take many forms. Dawn reflects on the differing mechanisms of power that, depending on who exercises it and how, are used to maintain control or assert supremacy.

Now aware of the human settlement, Caesar is faced with a difficult decision. His first instinct is to avoid violent conflict, but others advocate for a preemptive strike.

The intra-ape dissent is rooted in each ape’s experience with humans prior to the ape's rise. Humans raised Caesar. He’s seen the ugly side of humanity, but it exists in tension with more positive associations rooted in his upbringing. Most of his fellow apes only experienced the cruelty of humans and, as a result, are more hawkish. Ultimately, Caesar is their leader, and the group follows his lead.

The sudden appearance of an army of Apes ignites the panic Dreyfus was desperate to avoid. With public confidence waning, the need to regain power via the hydroelectric dam becomes imperative.

Malcolm returns to the forest, risking his life to appeal to Caesar. He explains why humans need to restore the hydroelectric dam within Ape territory. Caesar’s primary goal is to keep humans away and, in so doing, protect his fellow apes. Once Caesar understands that the humans are trespassing due to a need for electricity and will continue to trespass until they successfully restore the hydroelectric dam, Caesar agrees to allow a small group of humans to work within Ape territory. Once their task is complete, Caesar believes humans will leave and have no reason to return. In other words, working alongside humans in the short term allows the two communities to remain separate in the long term.

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes poses the most pivotal questions about what it means to be a good leader. Two factions, Ape and Human, have divergent goals and differing needs, but that fact doesn’t necessitate violent conflict. There is the path of diplomacy and compromise, and Caesar is keen to pursue that route. However, diplomacy is built upon mutual interest and relies on trust, which is challenging to cultivate and sustain at the dawn of this new world.

Despite dissent from both sides, Caesar and Malcolm begin working together in good faith. Meanwhile, simmering distrust begins to roil, revealing deep divisions within ape society. In a crucial test of his leadership, Caesar must navigate an increasing rift within his community. Simmering hatred leads to shifting allegiances that boil over into betrayal, with drama ascending to Shakespearian heights.

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes is true to the spirit of the original films but also manages to break new ground. Deftly weaving a web of hope and pessimism, it muddles the distinction between apes and humans, threatening the foundations of Ape society. It grapples with meaningful themes, old and new, posing intricate questions that lack easy answers.

Is trust between two warring factions possible? Is there such a thing as mutual interest?

Are the distrustful apes right about the fundamentally cruel nature of humanity? Does helping humans make Caesar a traitor to his own kind?

Is Caesar blinded by his compassion for humans? Does compassion constitute a vulnerability in a leader? Or does hatred and cruelty blind Caesar’s detractors?

Can Caesar build a better world for his people, and what role does humanity play in that future?

Can Caesar build a brighter future without compromising his values, and if not, what are the implications?

Is peaceful coexistence a possibility? Or is it merely wishful thinking?

I’ve only shared details from the first third of the film, so plenty of thrills and surprises are left to discover. I encourage you to watch Dawn of the Planet of the Apes and find your own answers to these questions. It is an astounding film that is well worth your time and is a masterful example of the science fiction genre firing on all cylinders.

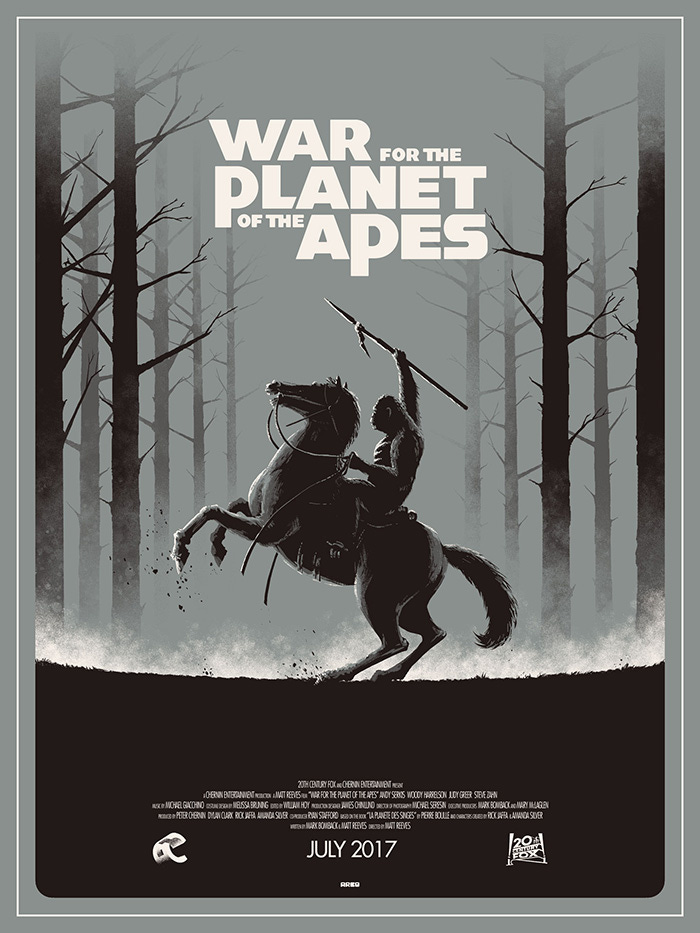

War for the Planet of the Apes (2017) ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

War for the Planet of the Apes continues Dawn’s story. So, I’ll keep my reflections brief and vague to avoid spoiling both films. As the film’s title suggests, the possibility of peaceful coexistence as conceptualized in Dawn doesn’t exactly come to fruition, and I don’t regard that fact as a major spoiler.

In a distinctively pessimistic franchise, did you expect a rosy end to Dawn? If so, have you been reading these retrospectives? Planet of the Apes is emphatically not a series fueled by hope.

If things at the end of Dawn were peachy keen, there would be no need for a third film, and make no mistake: War for the Planet of the Apes is a necessary and worthwhile continuation of Caesar’s story.

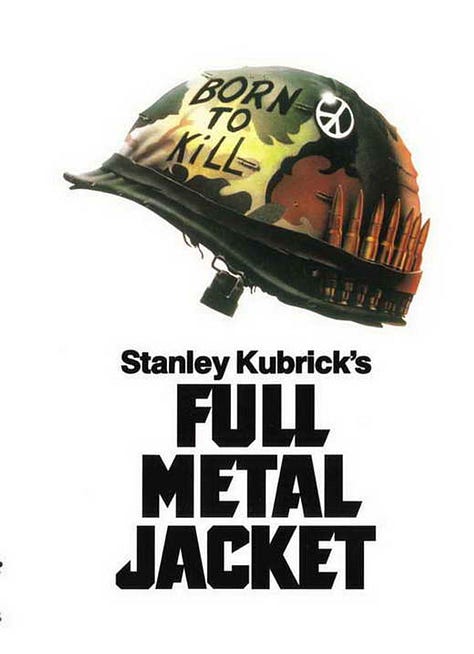

Although I regard Dawn of the Planet of the Apes as the best film in the franchise, War is an essential coda to Dawn that remains an excellent film in its own right. My stronger affinity for Dawn is primarily rooted in genre preference. Where Dawn brilliantly exemplifies sci-fi at its finest, War blends science fiction with the tone and sensibilities of war films, with more than a few references sprinkled throughout.

Genres don’t have rigid, defined borders, and genre fusion is a common practice that can produce novel and subversive results. I do not begrudge the fusion of science fiction and war genres; it is a fusion perfectly suited to the film and its thematic material. So, while I favor Dawn, it isn’t an objectively better film. They’re on par with each other, and War for the Planet of the Apes is an emotionally satisfying, suitably epic conclusion to Caesar’s story.

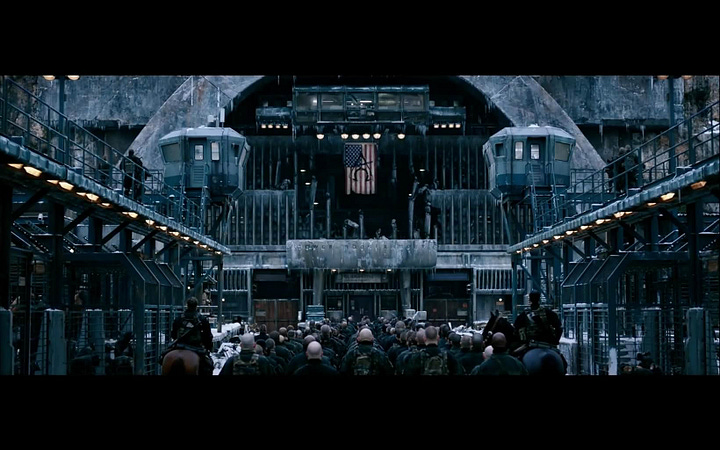

Two years after Dawn’s conclusion, Caesar and the apes are embroiled in an ongoing conflict with humans. The film begins with an explosive battle. Human troops sneak through the forest brush. Their uniforms all display the “AΩ” symbol, a reference to the world-ending atomic bomb seen in Beneath the Planet of the Apes. It’s scrawled in white on troops’ helmets, along with phrases like “Bedtime for Bonzo” and “Endangered species.”

After suffering immense personal loss and being faced with a violent conflict with no end in sight, Caesar is forced to make difficult decisions about the future of his community. Ultimately, his decisions lead him to cross paths with the human’s fanatical military leader, Colonel McCullough (Woody Harrelson). Where Dreyfus, the human antagonist in Dawn, sought to return humanity to a civilized state, The Colonel’s way of building a better future for humanity is predicated on the subjugation and slaughter of the apes that threaten humanity’s supremacy. As such, he embodies humanity’s atrocious propensity towards violence, fueled by the destructive desire to dominate nature.

It’s worth mentioning that the vast majority of “war films” produced after WWII (during which Hollywood churched out a slew of pro-war propaganda films) are, in fact, anti-war texts. That may seem counterintuitive, but even war films that seemingly valorize the combatants (e.g., Saving Private Ryan (1998)) are simultaneously preoccupied with rendering war's gory trauma and brutality. Even when soldiers are worshipped as heroes, the violent conflict they endured is hardly a cause for celebration. In keeping with the war genre’s broadly anti-war stance, War for the Planet of the Apes regards its bombastic conflict with solemnity and grief.

The film’s intertextual references to movies about the Vietnam War make its disdain for war irrefutable. At the time, the Vietnam War divided public opinion in America, causing civil unrest that is ultimately reflected in the original Planet of the Apes films. The domestic political divisions of the Vietnam War would emerge again after the American invasion of Iraq in 2003. In a surprise to no one, we didn’t learn our lesson and have continued to perpetuate the foolish notion that war is a path to peace.

With the gift of hindsight, the protracted conflict in Vietnam that snuffed out over 1.3 million lives (a conservative estimate) is almost universally regarded as a foreign policy boondoggle that epitomizes America’s unconscionable willingness to send citizens to slaughter in the misguided pursuit of geopolitical supremacy.

The films created in response to that shameful chapter in our history focus on the folly of America’s actions and the burden of trauma and grief that ordinary citizens were forced to bear for their country. Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, released only six years after America’s withdrawal from Vietnam, is among the most enduring portraits of the Vietnam War’s insanity.

Apocalypse Now tells the story of Captain Willard (Martin Sheen), who the American government sends to assassinate Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando), an American general who has gone insane and is now conducting rogue military operations deep in the jungles of Vietnam. War’s Colonel McCullough is directly inspired by Kurtz, visually and thematically.

I’m hesitant to say any more about War for the Planet of the Apes for fear of spoiling the richest parts of the film. Suffice it to say, War for the Planet of the Apes is an intelligently crafted combination of the science fiction and war genres, resulting in a worthy conclusion brimming with pathos.

Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes (2024) ⭐️⭐️⭐️

If Rise, Dawn, and War are a full, three-course meal, then Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes is a digestif of sorts. It takes place many generations after the events of War and features an entirely new cast of characters.

Because of its temporal setting, the distant future, Kingdom is the most detached from issues related to contemporary life. As a result, it feels more like fantasy than science fiction. Of the contemporary tetralogy, it is the least grim and, not coincidentally, the least substantive.

Our story follows Noa (Owen Teague), an Ape about to come of age. His father leads the village, a community that distinctly emphasizes a symbiotic bond between apes and a hawk companion.

On the night before his hawk ceremony, an unexpected encounter with a human invites disaster, forcing Noa to journey into unknown territory beyond his small world.

During his travels, Noa meets Rakka (Peter Macon), the last member of Caesar’s Order, a group dedicated to the study of Caesar’s teachings and the preservation of sacred texts that, due to illiteracy, apes can no longer read. With generations separating Noa’s world from Caesar's, Caesar’s gospel has been forgotten or twisted by bad actors to serve nefarious agendas.

As Noa continues his journey, he learns of a community led by a gorilla called Proximus Caesar. Despite his namesake, he is a dictator who is the antithesis of what Caesar purportedly stood for.

Yet, the possibility remains that Rakka’s conception of Caesar doesn’t reflect who Caesar actually was. Only we, the viewers, witnessed Caesar’s actions, and only we can decide if Rakka has properly characterized his idol or if his faith renders him blind to Caesar’s flaws. Caesar was, after all, a fallible mortal.

Insofar as the film primarily focused on Caesar as a historic leader and his values, Kingdom has the most thematic overlap with Battle for the Planet of the Apes. It is a much better film than Battle, which I regard as the lowest point in the Planet of the Apes franchise.

Despite easily clearing the low bar set by Battle, Kingdom’s plot is the most contrived and generic of the current teratology. It doesn’t bring new ideas to the table; instead, it opts to recycle and reflect on familiar material.

The cycle of violence continues long after Caesar’s story has ended. Seeds of distrust abound, weakening the possibility of a brighter future. In that regard, it treads the same ground as Dawn with less grace. Still, Kingdom remains a visually impressive popcorn flick that, like Rise, may be the foundation for greater things to come.

As of publication, the Planet of the Apes Franchise is available to stream on Hulu/Disney+, with the exception of Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes, which is currently in theaters.

And so we’ve reached the end of Acquired Tastes’ Planet of the Apes Retrospective, and I’m officially tired of writing about Planet of the Apes. It’s been a long journey, full of highs and lows, but I hope you’ve enjoyed the retrospective and that I’ve piqued your interest in the franchise.

What other franchise films would you want to see explored in depth? Leave a comment and let me know!

Until next week, please don’t talk to me about apes, my dear film freak.