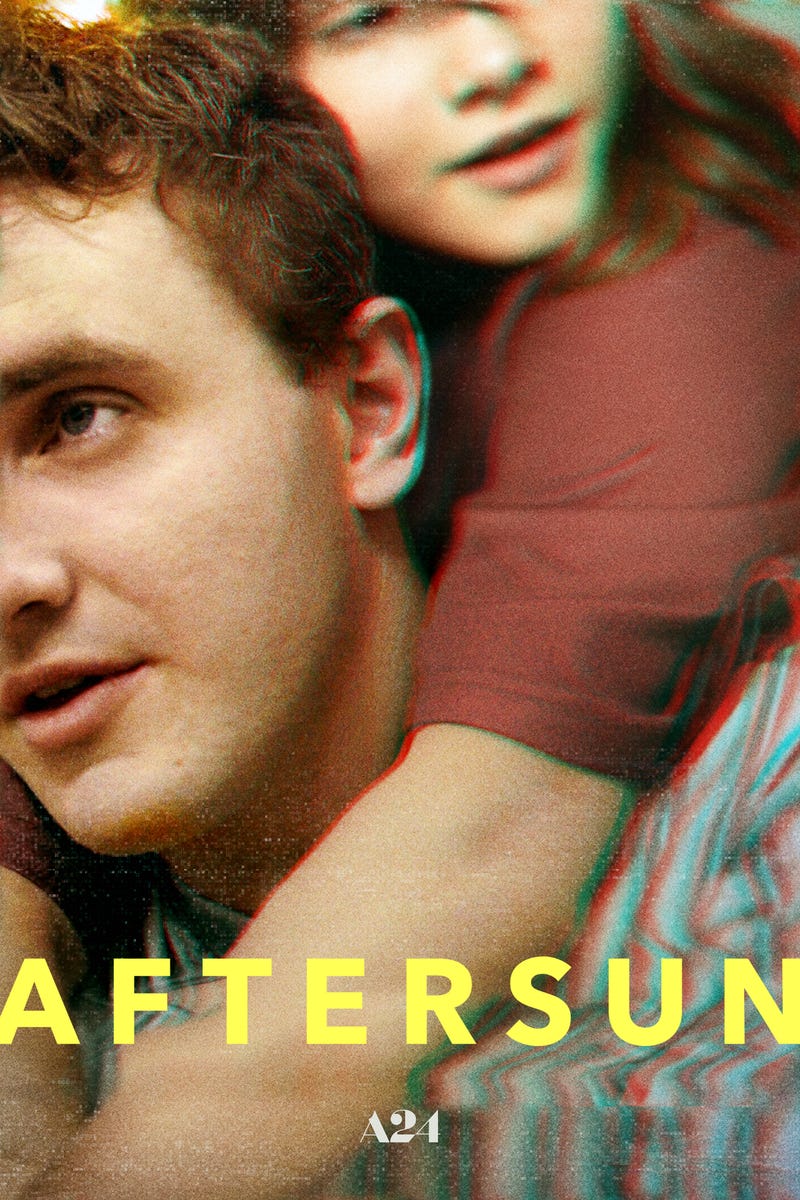

Aftersun, the auspicious debut from writer/director Charlotte Wells, vividly renders the emotional nuances of early adolescence, individuation, and the ensuing ramifications within parent-child relationships. Every facet of the film’s language works to create cinematic synergy: color, cinematography, symbolism, lighting, music, and sound design combine to create a film greater than the sum of its parts. Well’s displays stylistic restraint, eschewing flashy displays of excess in favor of subtle motifs and a strong focus on Sophie (Frankie Corio) and her father, Callum (Paul Mescal). The result is a cinematic tour de force propelled by the gentle touch of a warm breeze.

It all begins with a question. A retro camcorder gazes at a young father standing on a hotel balcony. His daughter, Sophie, speaks from behind the camera. She has just turned eleven and asks her father, whom she japes is turning one-hundred thirty-one, “when you were eleven, what did you think you’d be doing now?” He insists that she turn off the camera, his refusal to answer speaks volumes. So too does the realization that I’ve never considered asking my father such a question.

In Aftersun, Sophie reflects on a childhood trip with her father. Narratively, that’s the whole ballgame. Moviegoers craving the explosive action and narrative propulsion traditional to popular cinema may feel unmoored in Sophie’s memories. However, patient and perceptive viewers are rewarded with a moving exploration of the liminal spaces between childhood and adolescence, anchored by the extraordinarily naturalistic rapport between Sophie and her father.

No title cards convey time and place. Viewers are not coddled by expository dialogue. Glitchy, low-resolution visuals shot on handheld camcorders render the film’s temporal setting vis-à-vis the technical limitations of the era. The exact year eluded me until the hotel staff started dancing the macarena. Such is Aftersun’s approach to storytelling, a film that reads more like poetry than narrative fiction, and that may prove vexatious for audiences accustomed to more conventional fare. Enemies of narrative ambiguity are warned.

When Sophie asks why her father refuses to move back to their native Scotland, Callum responds, “There’s this feeling, once you leave where you’re from, that you don’t totally belong there again.” That sentiment was, in part, why I found myself at a 6:30 pm screening of Aftersun on Thanksgiving. Thankfully, Aftersun provided a veritable feast for the soul, leading me into emotional crevices I had outgrown and never expected to revisit.

Sophie’s trip with her father touches upon burgeoning facets of life that portend a rift in their relationship. Sophie observes a group of teenagers staying at the same resort. She sees couples kissing and drinking alcohol. After Sophie watches a teenage boy rub sunscreen lotion on his girlfriend’s back, Sophie experiences newfound discomfort when her father offers to help her reapply sunscreen. Sophie isn’t able to articulate why her relationship with her father is beginning to change.

The growing pains of being a tween are deeply resonant. Sexual awakenings and compulsory coupledom made me acutely aware of a longing that didn’t exist before. Where I was once content to pass the days with my parents, there now existed an omnipresent sense that I ought to be elsewhere. Being close to my parents, in whose arms I once sought comfort, suddenly made me feel embarrassed. I distinctly remember the siren call of friendships with older kids. Now the prospect of finding comfort with friends, or at the bottom of a bottle, was more appealing. Aftersun’s depiction of individuation allowed me to find an emotional clarity that had eluded me while I navigated similar changes in my own life.

Meanwhile, Sophie’s father grapples with a deep melancholy which he hides from Sophie. His silent suffering is not misguided martyrdom nor does his furtiveness obscure any dark secret. Rather, Callum is adrift in an unspecified sorrow, too afraid to say anything lest he drag others down with him. As I navigated my late adolescence and the years beyond, Callum’s emotional predicament registers as all too familiar.

As Callum compartmentalizes his anguish, and despite his best efforts, he isn’t a perfect father. His failures force him to shed the parental illusion of infallibility, causing Sophie to reckon with the fact that her father won’t always be there for her. He is just as flawed as the rest of us. It’s a lesson in heartache expressed in the film’s most emotionally painful scene. Yet even at its most painful, Aftersun remains tender and understated. Suffering never turns into a spectacle.

Aftersun could only exist outside Hollywood’s big-budget studio infrastructure. Charlotte Wells crafts a singularly subtle and stunning film that captures the complex emotions of a hyper-transient moment in maturation.

See you next week, my fellow film freak.