Sympathy for the Dead & Lust for Their Killers

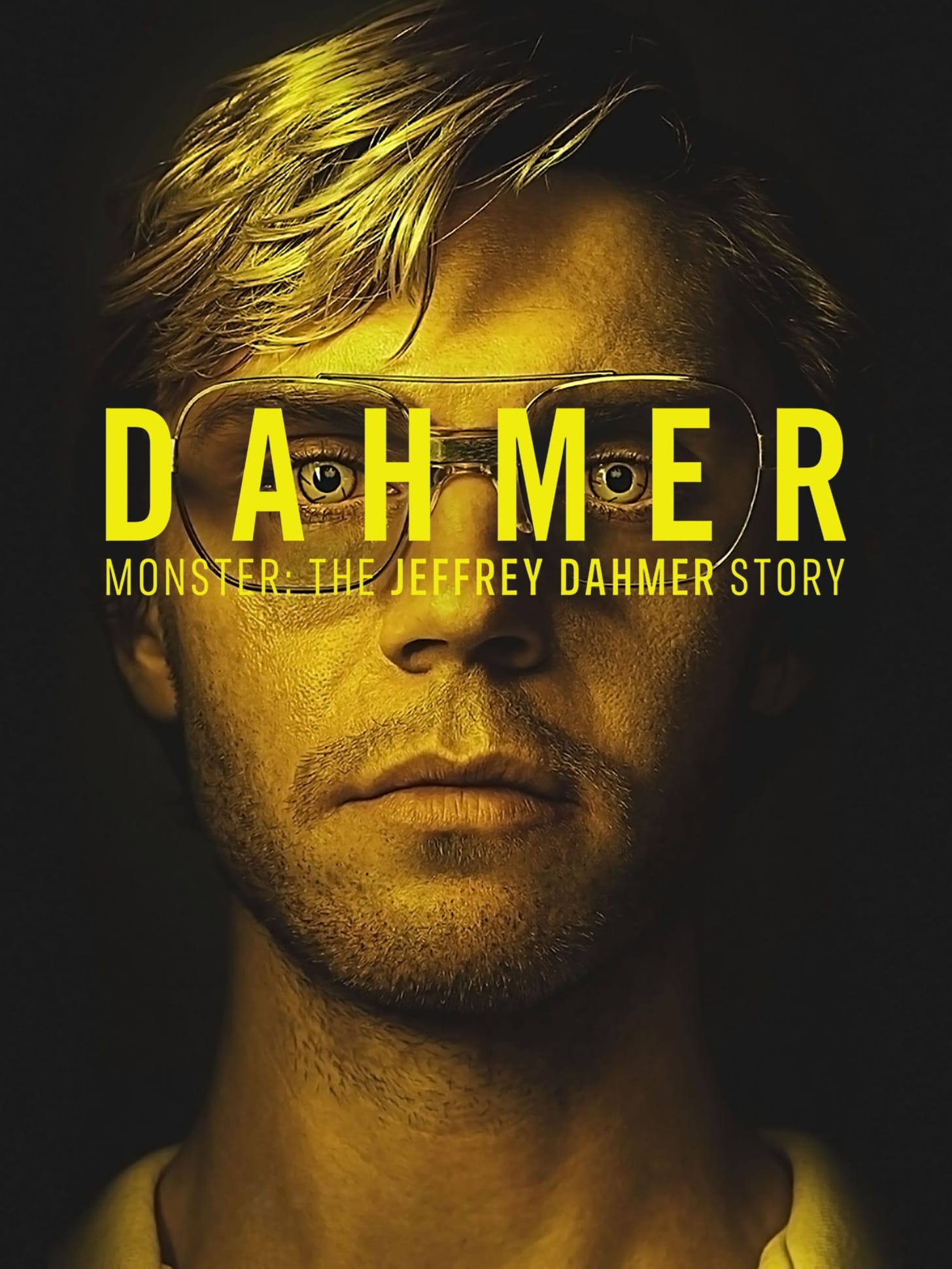

Dahmer - Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story (2022)

A Fetish for the Baddest Boys

With the recent release of Ryan Murphy’s Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menendez Story on Netflix and Lady Gaga’s performance in Joker: Folie à Deux (review forthcoming), I’ve been reflecting on the strange phenomenon where people thirst after serial killers and/or actors in serial killer cosplay.

I haven’t watched Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menendez Story, and I don’t intend to. The previous season, which focused on Jeffrey Dahmer, was incredibly disturbing in ways I did not anticipate but admittedly found fascinating.

So, this week, as I continue to work on my review of Joker: Folie à Deux, I wanted to share a review of Dahmer - Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story that I wrote in 2022.

Review: Dahmer - Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story

I cannot, in good conscience, recommend that anyone watch Dahmer - Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story (referred to henceforth as Dahmer, for obvious reasons). It’s a viewing experience as arduous as its title and as unpleasant as its subject. With that said, I must confess that Dahmer is among the most provocative pieces of horror I’ve had the pleasure of enduring -- and it is a work of horror, eliciting the fear and disgust requisite to the genre. Creative liberties allow a more thematically focused meditation on human nature and monstrosity. The result is a challenging and subversive riff on the monster movie, with resonance in the past, present, and future.

Created by Ryan Murphy and Ian Brennan, Dahmer debuted on Netflix. Within a month, it became the platform's second most-watched series of all time. Reactions were mixed. Many disavowed the show as disturbing (it is), exploitative (they’re right), and re-traumatizing to the families of Dahmer’s victims (I don’t doubt it). These criticisms, while entirely valid, strike me as par for the course. Nine hours with Jeffrey Dahmer is bound to be disturbing. The dramatization of real crimes is innately exploitative. The true crime genre is predicated on the suffering and misfortune of strangers. I can’t imagine a version of this story that doesn’t re-traumatize victims’ families.

True crime’s seemingly paradoxical appeal is similar to the horror genre. Both genres foreground violence and death. The viewers are confronted with immorality, abjection, and mortality -- all safely mediated by a screen. For those curious enough to gaze into the abyss, languishing in the morass of human nature can yield interesting insights.

Over nine hours, viewers inhabit multiple perspectives: Dahmer, Dahmer’s neighbor, his father, his mother, victims, and victims’ families. Although this storytelling structure occasionally lends itself to redundancy, it diffuses horror tropes and highlights social issues that allowed Dahmer’s monstrosity to fester unchecked.

The show’s defenders argue that the miniseries is a tribute to Dahmer’s victims. The show does spend time developing the victims to staggering dramatic effect. One episode is told from the perspective of Tony Hughes, one of Dahmer’s victims. It’s a hard sit that left me emotionally gutted, but it is, without a doubt, the best episode of the series.

Don’t let that fool you: Dahmer is, first and foremost, about Jeffrey Dahmer. This is an ethically dubious creative endeavor. Viewers do themselves a disservice by pretending otherwise.

Jeffrey Dahmer isn’t a sympathetic character, but Evan Peters’ soft-spoken portrayal of a lonely alcoholic with dark compulsions certainly evokes pity. Omnipresent homophobia isolates Dahmer. His sexual attraction towards men and his compulsion to kill and eat people are equally unspeakable, a reflection of societal attitudes towards homosexuality.

Dahmer drugs and sexually assaults his victims, foregrounding issues of consent and rape culture. He crudely lobotomizes victims with hopes of creating “sex zombies.” It’s a perverse example of the horror genre’s “over-reach plot.” Frankenstein is the classic example, where a man’s quest for god-like power violates the natural order.

Dahmer’s neighbor, Glenda Cleveland (Niecy Nash), navigates a “discovery plot,” another staple of the horror genre. The smell of rotting flesh creeps through a shared vent. Recurring screams, thuds, and power tools force her to reckon with unspeakable evil. Even after discovering the truth, Glenda is rendered powerless by skeptics: the Milwaukee police.

In horror, the skeptic is unable to accept the reality of their situation. Despite calls from Glenda and highly suspect interactions with Dahmer, the cops do nothing. They trivialize the concerns of black citizens and give a white serial killer the benefit of the doubt. It’s all too resonant amidst the Black Lives Matter movement.

As queer men continued to go missing, I contemplated the backdrop of the AIDS epidemic. Fifty-thousand Americans died before Ronald Regan publically acknowledged the existence of AIDS. Dahmer killed seventeen people in abhorrent and aberrant ways. What makes a monster? Is it the number of deaths or the method of murder?

What do you do if someone you love turns out to be a monster? Dahmer’s father, Lionel (Richard Jenkins), is horrified by his son’s actions but, as his father, still loves Jeff. Does Jeffrey Dahmer deserve that kindness?

The questions Dahmer provokes are difficult ones, and their answers are often uncomfortable. I was not disturbed by gore. It was the empathy I felt for every character, including Jeffrey Dahmer, that unsettled me the most.

I talked about this show in therapy for weeks. If that gives you pause, Dahmer might not be for you.

Until next week, stop getting horny for murderers, film freaks.