We Need to Talk About Camp

A NSFW consideration of Sontag's "Notes on Camp" and Showgirls (1995).

“Camp is a vision of the world in terms of style -- but a particular kind of style. It is the love of the exaggerated, the ‘off,’ of things-being-what-they-are-not.”

“Camp... is not a natural mode of sensibility… the essence of Camp is its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration… Camp is esoteric -- something of a private code, a badge of identity...”

-Susan Sontag in “Notes on Camp”

Blame the Met Gala

I’ve always been drawn to Camp, but my burning passion for the minutiae of Camp began in 2019. The Met Gala started the fire.

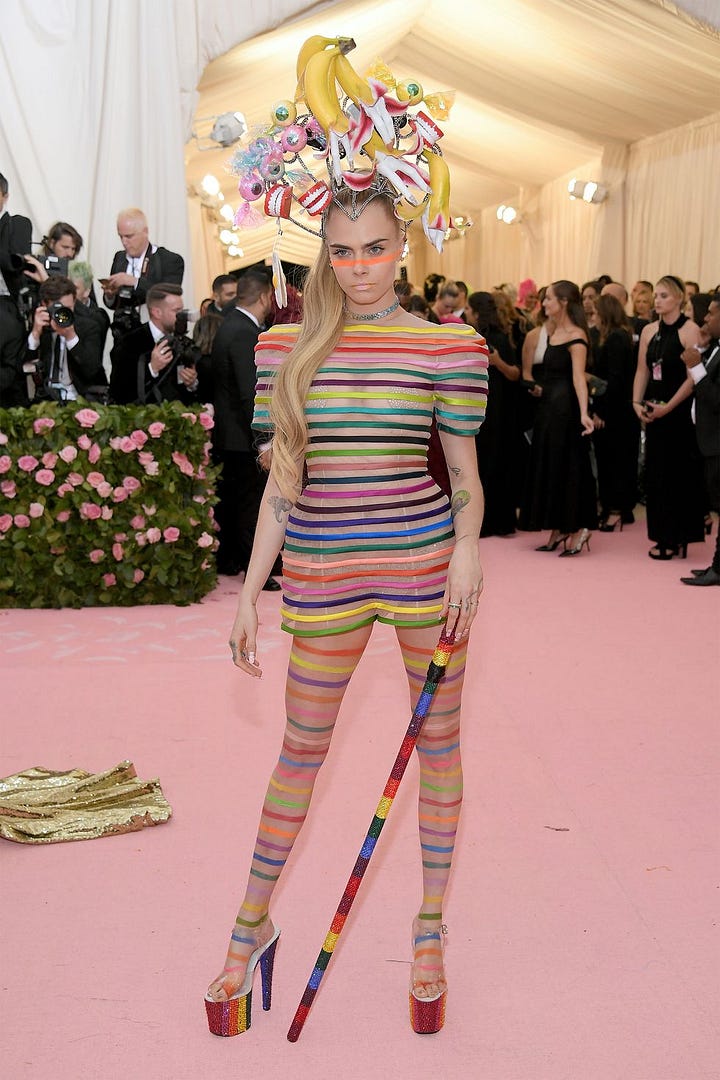

“Camp” was declared the Met Gala’s theme in 2019 and attendees were guided toward Susan Sontag’s “Notes on Camp” for reference. The same reference text produced a vast array of looks, serving as a microcosm of the confusion that surrounds Camp.

Camp is a difficult sensibility to define, so before diving into an example of cinematic Camp, it may be useful to consider photos taken at the 2019 Met Gala, an event with resonance beyond the world of film.

The internet buzzed and bickered, trying to determine what, exactly, “Camp” was. As evidenced by the range of looks that were photographed that evening, no singular understanding of Camp cohered.

Many attendees confused “Camp” and “campy,” which are divergent sensibilities, related, yes, but still separate and distinct.

I’m not deputized by the fashion police, but some of the evening’s looks failed to capture Camp’s true essence or entirely missed the mark.

And then there’s Violet Chachki, a drag queen that arrived in an elegant gown resembling an oversized, elbow-length glove. It is, in my opinion, the best look of the night because it reflects a conceptual grasp of Camp sensibilities as I’ve come to understand them.

The range of looks — their divergent sensibilities and varying levels of taste — reflect the elusive nature of Camp. As a sensibility, it cannot be easily defined.

For me, Violet Chachki’s look reads more “Camp” than the looks inspired by Vegas showgirls. That is because Violet’s identity as a burlesque performer is expressed in an artful, exaggerated fashion that is firmly rooted in the sincere sensibilities of her drag persona. By contrast, Kendall and Kylie Jenner’s Vegas-inspired looks may conform to traditional Camp aesthetics, but their personas have no relationship to Vegas showgirls. As a result, their attempts at Camp ring hollow and seem inauthentic.

“A sensibility is almost, but not quite, ineffable. Any sensibility which can be crammed into the mold of a system, or handled with the rough tools of proof, is no longer a sensibility at all. It has hardened into an idea . . . To snare a sensibility in words, especially one that is alive and powerful, one must be tentative and nimble.”

-Susan Sontag in “Notes on Camp”

To explore the contours of Camp is to grapple with semantics (i.e. Camp is not the same as campy). The discourse around Camp can get passionate because Camp’s very nature resists the possibility of a stable, unified definition. It’s a sensibility that is sensitive to context, and the essence of “true Camp” is liable to change across mediums. The Camp sensibilities displayed in Met Gala fashion differ from Camp as seen in literature, which itself differs from cinematic Camp.

Defining Camp (with a Capital C)

Susan Sontag’s seminal essay “Notes on Camp” constitutes the foundation of our foray into the sensibilities of Camp and its relationship to taste.

“I am speaking about sensibility only -- and about a sensibility that, among other things, converts the serious into the frivolous -- these are grave matters. Most people think of sensibility or taste as the realm of purely subjective preferences, those mysterious attractions, mainly sensual, that have not been brought under the sovereignty of reason...”

“There is taste in people, visual taste, taste in emotion - and there is taste in acts, taste in morality. Intelligence, as well, is really a kind of taste: taste in ideas... taste tends to develop very unevenly. It's rare that the same person has good visual taste and good taste in people and taste in ideas.”

-Susan Sontag in “Notes on Camp”

Additionally, this week I offer Showgirls (1995) — directed by Paul Verhoeven, known for Robocop (1987), Total Recall (1990), Basic Instinct (1992), and Starship Troopers (1997) — as an example of a film that embodies the true essence of cinematic Camp. As we discuss Sontag’s theoretical musings on Camp sensibilities, Showgirls will act as our “north star” when considering Camp’s cinematic praxis.

Watching Showgirls for the first time is an otherworldly experience. The film is preceded by its reputation, and yet one cannot truly fathom the level of unreality which pervades this film. It needs to be seen to be believed, and still, the film’s appeal may elude first-time viewers. For the uninitiated, it may register as overwhelmingly strange and off-putting. That’s because it is.

“To start very generally: Camp is a certain mode of aestheticism. It is one way of seeing the world as an aesthetic phenomenon… the way of Camp, is not in terms of beauty, but in terms of the degree of artifice, of stylization.”

“To emphasize style is to slight content, or to introduce an attitude which is neutral with respect to content. It goes without saying that the Camp sensibility is disengaged, depoliticized -- or at least apolitical.”

“True, the Camp eye has the power to transform experience. But not everything can be seen as Camp. It's not all in the eye of the beholder.”

-Susan Sontag in “Notes on Camp”

Showgirls is a head-spinning experience unlike any other. Allow me to offer a sample of Showgirl’s dialogue, exaggerated acting, and overall emotional instability.

For context: James and Nomi met while dancing (poorly) in a nightclub. James tells Nomi that she isn’t dancing, she’s “teasing his dick,” and he offers to be her dance teacher. In response, she knees him in the testicles. This assault lands Nomi in jail for the night. James bails her out in the morning. She rejects his advances. Later, Nomi works at Cheetahs, a strip club. Cristal, the leading Vegas showgirl, pays a premium for a private dance from Nomi. Reluctantly, Nomi agrees. Nomi grinds on Cristal’s boyfriend, Zack, until he climaxes. Cristal watches. It’s weird. James just so happens to be at Cheetahs and glimpses the private lap dance. He is promptly bounced from the club. The next morning James knocks on Nomi’s door:

Removed from context, the scene doesn’t make much sense. In context, it makes even less sense. That is the beauty of Camp.

It’s a straightforward conversation, but its presentation evokes so many questions: Why is James so intent on helping a woman that has told him “no,” physically assaulted him, got him fired from his job, and expressed no gratitude for bailing her out of jail? Despite all of that, James shows up at Nomi’s home unannounced — begging the question, how the hell does James know where she lives? — and expected a favorable outcome?

In this short clip: a man shows up to a woman’s home, says she’s talented, drops pearls of wisdom such as “dancing ain’t fucking,” “man, everybody got AIDS and shit” and “you fuck them without fucking them.” He seethes at the prospect of Nomi wasting her talent, is rejected, then leaves.

Such is the emotional landscape of Verhoeven’s Vegas: irrational, outlandish, and emotionally unstable. Every interaction feels strange and absurd.

For film freaks that find the otherworldly oddity of Showgirls alluring, it is streaming on Amazon Prime for the next six days (as of publication). For readers uninterested in Verhoeven’s otherworldly odyssey into Las Vegas, I will include clips from the film and, wherever possible, allow Verhoeven to speak on the film’s behalf.

Paul Verhoeven on Showgirls

“Is it all just tits and ass?... some people might say so. Even if this perception were true, that’s fine with me…”

-Paul Verhoeven in Showgirls: Portrait of a Film

“Realizing that some dancers used sexual relationships to get the top spots in the big Vegas shows… out of all this emerged a film about a young woman with a disturbed background that is not revealed until the end of the picture. Her name is Nomi, and she goes to Las Vegas with the dream of becoming a dancer in one of the big shows. She has to begin in one of the strip clubs, in which she claws and manipulates her way up the ladder of success. She uses her strange and complex relationship with Cristal, the lead dancer in the biggest show, to get what she wants. And she discovers at each rung of the ladder, she has to pay a higher price for what she is getting. Ultimately, she refuses to pay with her soul.”

-Paul Verhoeven in Showgirls: Portrait of a Film

After Showgirl’s release, Verhoeven adeptly navigated the film’s fallout. Showgirls won “worst film” and “worst director” at the 1995 Razzies, a sort of “anti-Oscars” award show that recognizes the worst films of the year.

Verhoeven was the first director to attend the Razzies and accept both of his “awards”. Perhaps this reflects a degree of humility, willing to laugh at his own failure. Or, perhaps, he would rather laugh with audiences rather than be laughed at. Verhoeven would have you believe he was in on the joke, that Showgirls isn’t an accidental embarrassment. However, in Showgirls: Portrait of a Film — a photography book released alongside the film — Verhoeven’s writing betrays the unmistakably earnest foundation upon which Showgirls is built.

“As a young Dutchman, I was entranced by American musical films, and the opportunity to direct one has been the fulfillment of a lifelong dream…I was remembering all those big MGM musicals that I had watched over and over as a kid. I loved… West Side Story… I always wanted to make a movie with a lot of music and dancing, and I liked the idea that this was not going to be a “highbrow” musical… Ironically, with Showgirls, I got to direct an MGM musical!”

-Paul Verhoeven in Showgirls: Portrait of a Film

He provides specific references and inspirations, allowing insight into the type of film Verhoeven was attempting to make:

“I thought of West Side Story and Flashdance as the musical inspirations for this movie… I ended up studying Frederico Fellini's 8 ½ and Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil for inspiration.”

-Paul Verhoeven in Showgirls: Portrait of a Film

He unironically references legendary filmmakers such as Fellini, Wells, and Hitchcock. He references cinematic techniques, like the use of Steadicam cinematography, which he employs in Showgirls.

“Camp is either completely naive or else wholly conscious (when one plays at being campy).”

“In naïve, or pure, Camp, the essential element is seriousness, a seriousness that fails. Of course, not all seriousness that fails can be redeemed as Camp. Only that which has the proper mixture of the exaggerated, the fantastic, the passionate, and the naïve.”

-Susan Sontag in “Notes on Camp”

He cites specific scenes from iconic films, outlines their techniques, and explains how he imbued Showgirls with the same cinematic brilliance:

“There’s a scene… in which Cristal and Nomi are talking in a restaurant… where I ‘steal’ from North by Northwest. If you recall the scene between Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint on the train, he shoots first over the shoulders, and then moves closer and closer, in a simple and very elegant way. That’s one of my favorite dialogue scenes in all of movie-making, and I borrowed from it shamelessly.”

-Paul Verhoeven in Showgirls: Portrait of a Film

Now, let’s consider Verhoeven’s scene, which finds Nomi and her rival, Cristal, bonding over shared lived experiences:

The dissonance between Verhoeven’s Hitchockian inspirations and the realities of the “doggy chow” sequence encapsulates the sensibilities of camp. To appreciate this moment as Camp requires viewers to bridge the chasm between artistic intent and the art’s impact. Viewers transverse the chasm on a tightrope, taking seriously the artist’s noble intentions and holding it in tension with the hilariously inept final product.

In other words, by making Showgirls Verhoeven really thought he was doing something. Specifically, he was attempting to make a movie about sex and power dynamics in the entertainment industry.

“We knew rather early in the development of this movie that sexuality and sexual power would be one of the core dramatic issues… The emerging prospect of trying to direct an adult movie that deals with naked dancers within the arbitrary “R“ structures of the rating board made me very unhappy… I have been accused of being deliberately provocative in insisting upon making an NC-17 film, and I suppose that my insistence is provocation in its way. But I think of myself as provocative in a different sense: as a Director, who explores the difference between reality and the way in which we usually see reality portrayed. I feel that there is a huge discrepancy between what life really is, and what we are supposed to see in the movies. There are many aspects of life that are not publicly acknowledged, and that many people don’t want to see as a reality…”

-Paul Verhoeven in Showgirls: Portrait of a Film

This scene, in which Nomi auditions for the stage show “Goddess” is Verhoeven’s rendering of an ugly reality:

I think Verhoeven is attempting to expose the dehumanization that women are subjected to within the patriarchal power structures of the entertainment industry. It’s possible to argue that this scene, with its shameless vulgarity, manages to articulate Verhoeven’s critique. In my opinion, a critique is present but it is distorted by Verhoeven’s leering male gaze. The film cannot effectively articulate its critique because it’s too distracted by boobs and butts, compounded by Verhoeven’s fundamental misunderstanding of female empowerment and its relationship to sex. In the “Tony Moss is a Prick” scene, audiences likely aren’t surprised by the fact that Vegas big-wigs aren’t kind people, but they’re liable to be shocked by the extremity of its presentation. Tony Moss, a self-proclaimed prick, is a male chauvinist with power that allows him to spew misogynist sentiments at women on a seemingly arbitrary basis.

“I am strongly drawn to Camp, and almost as strongly offended by it. That is why I want to talk about it, and why I can. For no one who wholeheartedly shares in a given sensibility can analyze it; he can only… exhibit it.”

“To name a sensibility, to draw its contours and to recount its history, requires a deep sympathy modified by revulsion.”

-Susan Sontag in “Notes on Camp”

In the decades since Showgirls' release, systemic sexual misconduct has been revealed to be endemic to the entertainment industry. This reality, exaggerated by Verhoeven’s maximalist sensibilities and the flippancy of his rendering of reprehensible behavior, undermines Showgirl’s noble intentions. Perhaps ascribing nobility to any part of Showgirls is charitable to the point of delusion. There’s no denying that Showgirls is offensive, but its repellant qualities are what I find so interesting and are a requisite part of camp.

“When the theme is important, and contemporary, the failure of a work of art may make us indignant. Time can change that. Time liberates the work of art from moral relevance, delivering it over to the Camp sensibility. . . things are campy, not when they become old - but when we become less involved in them, and can enjoy, instead of be frustrated by, the failure of the attempt.”

-Susan Sontag in “Notes on Camp”

Considered through a charitable lens, Showgirls seeks to liberate women by normalizing their sexuality. Verhoeven positions his art in opposition to censorship and those who champion it.

“I don't think that the religious moralists or right-wing feminists are heartless or cynical, but I think that they are similarly misguided in their attacks on sex in movies. Fundamentally, they both argue that a woman showing her tits is being degraded, is being exploited, is being humiliated, and that the act of showing her tits contributes to the downfall of civilization. I don't think that's true.”

-Paul Verhoeven in Showgirls: Portrait of a Film

Part of me agrees with Verhoeven’s sentiment or, at least, doesn’t regard it as patently absurd. However, Verhoeven’s continued reflections on sexual dynamics are woefully misguided and inevitably lead the film astray.

“What that woman is doing [when showing her tits] is demonstrating our strong human instinct for procreation. Most heterosexual and bisexual men like to see tits and ass because those sights stimulate our sexual drives, our natural desire to fuck and create babies. Most women like to show off their bodies in skirts that reveal their legs or blouses that emphasize their breasts, because they like to use their sexual power – they know that dressing this way will attract men who will ultimately give them babies. (Of course, this is not a conscious process.) That’s the simple biology lesson of it.”

-Paul Verhoeven in Showgirls: Portrait of a Film

His solution to the problem he identifies is not an indictment of the patriarchal structures that perpetuate violence in the entertainment industry. Verhoeven ultimately creates a text in which men aren’t the issue, prudes are. It is not the patriarchy oppressing women, it’s the conservative movement’s inability to accept the biological reality that, according to Verhoeven, everyone wants to fuck all the time to make babies. Within his framework, female sexuality isn’t ever concerned with female gratification. It’s outlandish that women would have sex for pleasure. Rather, Verhoeven asserts, women unconsciously cater to the male gaze for one of two reasons: to make babies or manipulate men.

Nomi’s character is Verhoeven's apotheosis of the “manipulative power” of female sexuality. To her, sex is weaponized and enables her to climb the industry ladder. Verhoeven seems to regard sexual manipulation and sexual empowerment as synonymous, an erroneous conflation that weakens the foundation of Showgirls’ feminist intentions to the point of instability. That instability is instrumental in creating Showgirls’ pervasive sense of unreality. That unreality is a result of the dissonance between Verhoeven’s intention and the film he ultimately made. Herein lies the failed seriousness requisite to Camp.

Ultimately, Showgirls is a film preoccupied with sex and power, predicated on Verhoeven’s delusional understanding of the thematic material. It’s no wonder that the resultant film feels wrong, uncomfortable, and strange. This delusional dissonance, the makings of Camp, are clearest in Verhoeven’s depictions of sex.

“…all of the sex scenes in this film have a purpose, in addition to simply stimulating sexual enjoyment.”

“Despite the fact that everybody fucks, and that sexuality is simply a mammalian characteristic, American movies, do not portray sex, particularly realistically, if, at all.”

“In my films, I hold the mirror up to life. What you see is the sex and violence that already exists in modern societies… sometimes I push beyond the framework of reality, because that’s my pleasure.”

-Paul Verhoeven in Showgirls: Portrait of a Film

Keeping in mind Verhoeven’s intention to portray sex realistically, I’d like to consider the infamous “pool sex scene.”

“In a later scene in Showgirls, after Nomi has learned that Zack will be holding auditions for Cristal’s understudy… she goes home with him and fucks him in his swimming pool. I shot it with a kind of romantic feeling, but again, I am using the knowledge that the audience has about her ulterior motive. I don’t do it as straight fucking. I have her fuck him the way she did in the lap dance, so that this scene echoes the earlier one, and the audience can see that Nomi is doing essentially the same thing in a different way. It is camouflaged as a romantic scene, but the audience emotionally absorbs that it is about something else, and they gain another insight into her character.”

-Paul Verhoeven in Showgirls: Portrait of a Film

The irreconcilable tension between the sequences’ stated intention and the realities of its aesthetic presentation is a perfect distillation of the film’s Camp sensibilities. That Verhoeven considers this scene “romantic” is laughable. The assertion that Verhoeven’s film wants to depict sex realistically cannot be taken seriously if this is what Verhoeven considers a realistic depiction of sex:

“Camp taste turns its back on the good-bad axis of ordinary aesthetic judgment. Camp doesn't reverse things. It doesn't argue that the good is bad, or the bad is good. What it does is to offer for art (and life) a different -- a supplementary -- set of standards.”

-Susan Sontag in “Notes on Camp”

There is no question that Showgirls is, all things considered, a flop. However, like Nomi's convulsive pool sex, it’s a flop unlike anything I’ve ever seen.

The outlandish, misguided, and reductive facets of Showgirls are what make the film worth watching, especially considering Verhoeven’s stated intentions. Intent and impact cannot be reconciled, resulting in an accidental masterwork of Camp.

For those looking for a more robust deconstruction of Showgirls, the 2019 documentary You Don’t Nomi is a spectacular retrospective dedicated to this cinematic “masterpiece of shit.”

Thanks for your attention, I know this week’s newsletter was a long one. Camp is something that I value, and I hope you too can indulge in the joys of Camp — even if Showgirls isn’t the movie for you.

So concludes this opening reflection on Camp’s sensibilities. I plan to return to Camp in the coming weeks so be sure to:

Or, if there are other film freaks that you know, please:

If you have any thoughts on Camp, Showgirls, or any other film recommendations, please:

See you next week my fellow film freaks.

GREAT post!

Have you watched Reprisal on Hulu?

Twin Peaks also comes to mind. Especially any scene in the local diner.

This is great!