Nonsense is My Favorite Sense

"If I had a world of my own, everything would be nonsense. Nothing would be what it is because everything would be what it isn't. And contrariwise, what it is, it wouldn't be, and what it wouldn't be, it would. You see?"

-Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Caroll

This week, I watched Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (1971) with my boyfriend. It was his first time seeing the film. I, on the other hand, grew up watching it. I’ve always loved the film. However, revisiting it with a fully developed prefrontal cortex, Willy Wonka delighted me more than ever. It turns out Gene Wilder’s Wonka speaks my language.

“A little nonsense now and then is relished by the wisest men.”

-Wonka, singing softly into Mr. Salt’s ear

If you know me well, you know I have a strong affinity for nonsense. It’s why Lewis Carol’s Alice's Adventures in Wonderland ranks among my favorite books. The absurdity of Alice’s adventures in Wonderland reflects a child’s perception of the adult world. Adults' lives are governed by a logic that, to a child, isn’t liable to make much sense.

It’s why young children ask so many questions and respond to every answer with, “But why?” They’re attempting to make sense of the world around them, yet adults' straightforward answers sate their curiosity about the wonderful world around them.

At the beginning of her story, Alice doesn’t want to learn. She doesn’t want to read about the world, she wants to experience it. So, she journeys to a world where playful nonsense reigns supreme. The child’s mind, unbound to notions of reason, is fit to contend with a world governed by nonsense. However, Alice doesn’t thrive in a world of nonsense. Ultimately, she longs for home and, upon returning, is relieved to return to her status quo, happy to accept mundanity alongside stability.

Charlie’s journey through Wonka’s factory resembles Alice’s adventures in Wonderland, with some notable inversions. This is particularly true of Mel Stuart’s original film, Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, a timeless tale that finds its characters in a wonderous world tinged by unpleasant realities.

To discuss my enduring love for Gene Wilder’s portrayal of Willy Wonka, it’s worth considering subsequent, less successful incarnations of the character to elucidate what makes Wilder’s performance so endlessly endearing.

Wonky for Willy Wonka

Willy Wonka has been on my mind ever since seeing last year’s Wonka (2023), which I reviewed upon release and loathed. I called Wonka a “toothless cash grab that banks on a pre-existing intellectual property that brings nothing new and, even worse, seems to fundamentally misunderstand the unique selling point of Willy Wonka’s character.”

Wonka tells the story of the young, starry-eyed chocolatier achieving capitalist success against the odds with nothing but a dream, a can-do attitude, and the memory of his mother. It’s too earnest, leading me to the declaration that “candy has never been cornier.”

Read my full review of Wonka:

I stand by my rebuke of Wonka. It’s a toothless product masquerading as a movie that exudes what I call “the Disney Glaze,” denoted by a dirth of mise-en-scene. Films with the Disney Glaze lack texture. Everything is too clean. A ragged coat looks as good as new. Every speck of dirt or grime has been deliberately smeared onto the actor's cheeks. Destitute orphans exude precious theater-kid energy, beaming with whitened smiles. A drunkard's disheveled hair has been carefully styled and teased until it's perfectly unkempt.

Wonka, a sanitized capitalist product, has seemingly forgotten, as I wrote, that “Willy Wonka’s appeal is his weirdness…Willy Wonka is, and always has been, a raving lunatic. His madness and his genius go hand-in-hand. It’s what makes him interesting to watch.”

Candy Coated Capitalism

Minutes into Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, my boyfriend said, “This is a film about capitalism, isn’t it?” His adult eyes quickly identified what the eyes of a child had missed. Under the morality play that punishes bratty children with thinly veiled violence befitting a Grimm’s Fairy Tale, there lies a message about the soul-crushing cynicism of capitalism. Children certainly aren’t born with an innate understanding of the responsibilities of adulthood, so many of which are inextricable from capitalism and the imperative to survive.

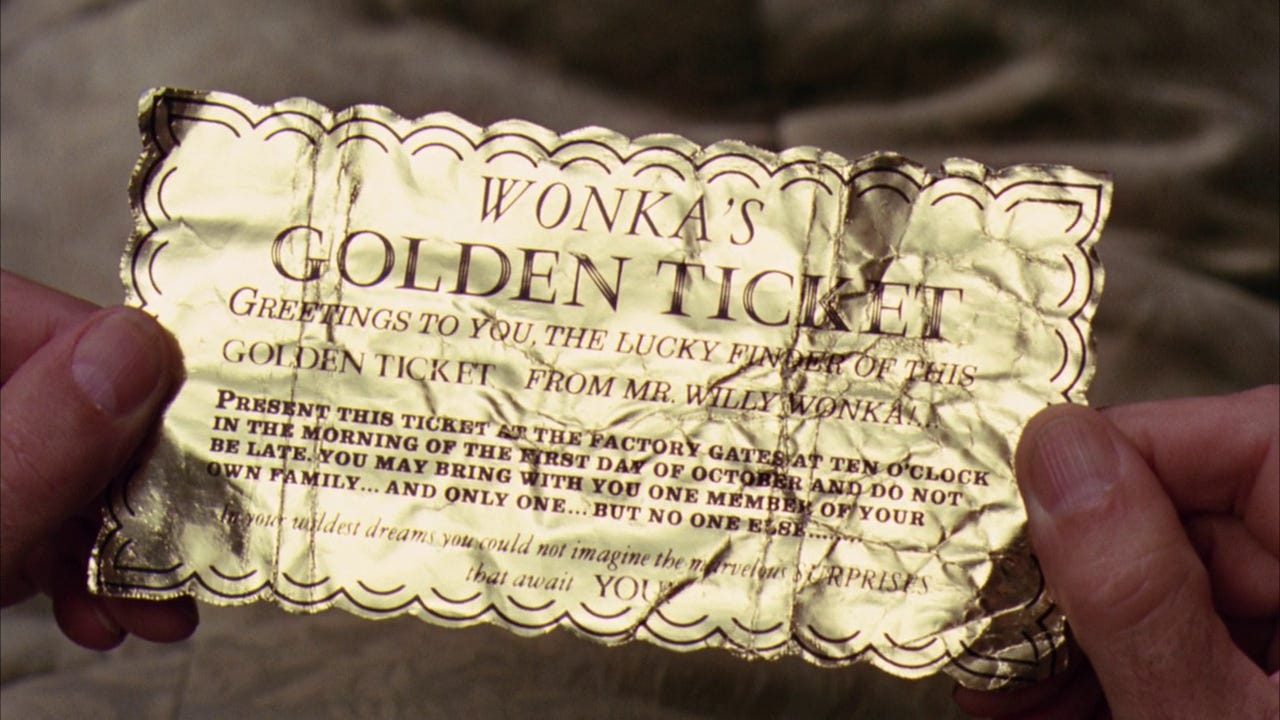

By dint of its focus on production and consumption, capitalism is at the forefront of Willy Wonka’s text. It holds two conflicting notions in tension: on the one hand, there’s the notion that Charlie is just as likely to find a golden ticket as any other consumer. This line of reasoning may stoke Charlie’s hopes and dreams, but, in reality, it’s an over-simplified borderline nonsensical presentation of how Wonka’s capitalist sweepstakes actually works.

It’s possible for Charlie to find a golden ticket, and indeed he does. However, as the entire globe frantically purchases Wonka Bars, the odds that Charlie finds a golden ticket are infinitesimal. And yet, in defiance of the odds, Charlie finds his golden ticket, earning himself a trip to Wonderland by way of Willy Wonka’s altruistic sweepstakes (or savvy marketing, depending on your relationship to the absurdities of capitalism).

Is the film really suggesting that capitalism puts everyone on equal footing, affording them the opportunity to succeed on the merits of their character? Notionally, it would seem so. But, of course, we know that’s nonsense.

In Burton’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (2005), which broadly assumes its viewer is an idiot and so feels the need to explain everything, Grandpa George says the quiet part aloud:

GRANDMA JOSEPHINE: You have as much chance as anybody does.

GRANDPA GEORGE: Baldersnap! The kids who are going to find the Golden Tickets are the ones who can afford to buy candy bars every day. Our Charlie gets only one a year! He doesn't have a chance!

GRANDMA JOSEPHINE: Everyone has a chance, Charlie.

Ultimately, Grandma Gorgina, whose sole trait is her senility, is also the voice of untempered optimism. With her dubious grasp of reality, she reassures Charlie that “nothing is impossible.”

The story of Charlie Bucket, impoverished but pure of heart, finding a golden ticket against all odds may not register as a metaphor for capitalism’s empty promises. That’s because the golden ticket isn’t the signifier of success; it's a signifier of opportunity. Success, as it is defined by the Golden Ticket, is solely determined by Willy Wonka. Furthermore, the embodiment of success is also its victim, forced into a solitary existence.

Growing up in poverty, Charlie is all too familiar with economic hardship. His luck is a narrative contrivance that demands suspension of disbelief and, in that regard, primes viewers for their entry into Wonka’s factory, a magical place whose colorful confections belie an emptiness in the confectioner’s world-weary soul.

Herein lies the essential difference between Alice and Charlie: Alice learns lessons in Wonderland, whereas Charlie stands to teach Wonderland’s creator a thing or two.

“Oh you can't get out backwards, you have to go forwards to go back.”

-Gene Wilder as Willy Wonka

Tim Burton’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

Burton’s take on the film understands that “Wonka’s appeal lies in his weirdness,” but cranks up Burton’s signature quirkiness to an eleven. Its visuals don’t exude the soulless Disney Glaze. Instead, Burton imposes his quirky, maximalist aesthetic onto Wonka’s world.

Despite the ocean of disdain audiences harbor for this film, I think the results are mostly successful. There’s been plenty of handwringing about the gaudy visuals, but the film addresses this critique.

During the glass elevator sequence, amid explosions of fireworks fired by Oompa Loompas, Mike Teavee says what so many of you seem to be thinking: “Why is everything here completely pointless?”

Without missing a beat, Charlie replies, “Candy doesn’t have to have a point. That’s why it’s candy.”

Charlie’s answer is Burton’s justification for his film’s creative choices, but Charlie’s answer betrays a fundamental misunderstanding. Candy is not pointless. Candy is about pleasure.

Whether or not you find Burton’s brand of Wonka palatable is a question of taste. Depp’s more awkward and openly misanthropic approach to the character certainly has the potential to leave behind a bitter taste.

Mrs. Gloop: Where is my son? Where does that pipe go to?

Willy Wonka: That pipe, it just so happens to lead directly to the room where I make the most delicious kind of strawberry-flavoured chocolate-coated fudge.

Mrs. Gloop: Then he will be made into strawberry-flavoured chocolate-coated fudge? They'll be selling him by the pound all over the world?

Willy Wonka: No, I wouldn't allow it. The taste would be terrible. Can you imagine Augustus-flavoured chocolate-coated Gloop? Ew. No one would buy it.

Upon seeing Johnny Depp’s fuck ass bob, my boyfriend astutely pointed out that he’s essentially in full drag. He hit the nail on the head. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory embraces the excesses of camp and, in so doing, is happy to get lost in the sauce.

In no world is Burton’s film superior to the 1971 original, but it isn’t bad. It’s different: colder and less charming in the traditional sense.

In Burton’s film, Willy Wonka a reclusive, pale freak who barely masks his disdain for his visitors. His retorts are often glib and dismissive. On multiple occasions, his facial expressions betray outright disgust. He is far more openly misanthropic than his predecessor, and, in a film that wears its malevolence on its sleeve, Depp’s weirdo Wonka works for me.

Everything in this room is eatable, even I'm eatable! But that is called ‘cannibalism’, my dear children, and is in fact frowned upon in most societies.

-Johnny Depp as Willy Wonka

Burton utilizes CGI to try to convey the massive scale of Wonka’s world, but the underdeveloped technology circa 2005 lands the film somewhere within the uncanny valley. There is a texture to the film, but it’s conspicuously smooth. Is it ideal? No. Does it ultimately fit the film? I think so.

The intangibility of the film’s visuals reflects the emotional inaccessibility of Depp’s Wonka. He’s more of a caricature than a real person, driven by Daddy issues to build an edible empire. His character is fundamentally queer: not with regard to his sexuality, which is utterly immaterial to the film. It is his rejection of traditional family systems and androgynous gender expression that registers as queer. Relegated to the fringes of society by his difference and forced into seclusion by his genius, it stands to reason that his edible, industrial Xanadu would reflect his esoteric nature and complete disconnection from the real world.

Why Wilder’s Wonka Works

Gene Wilder’s characterization of Wonka is certainly “tinged with esoteric misanthropy,” but upon revisiting his factory, it became clear that his character's abiding appeal is not rooted in latent malice. If it were, Depp’s Wonka would be more interesting. Instead, it is Gene Wilder’s penchant for nonsense and doublespeak, spoken with a wry weariness, that continues to feed my soul all these years later.

“So much time and so little to do. Wait a minute. Strike that. Reverse it. Thank you.”

-Gene Wilder as Willy Wonka

Wonka’s World and Wonderland have quite a bit in common. So too does Charlie’s normal world resemble Alice’s status quo. Both are confusing places governed by adults who don’t make much sense. A sense of confused alienation crops up around education for both Charlie and Alice.

Before he finds his ticket, Charlie’s teacher, Mr. Turkentine, is presented as the figure of educated authority. Mr. Turkentine is a deeply unserious person, though that never seems to occur to him as he babbles nonsense that illustrates adults’ general inability to explain to children what’s happening and, more importantly, why.

Mr. Turkentine’s manner of speech starkly contrasts with the plain speech of the humble Bucket family. As a teacher, his lack of clarity poses a problem for his students. Nevertheless, a paragon of good behavior, Charlie Bucket unquestionably swallows the nonsense of the world around him, even if it doesn’t make sense.

Mr. Turkentine starkly contrasts the clarity Willy Wonka offers Charlie within the metaphorical Wonderland of Wonka’s Factory. Wonka’s language is anything but straightforward, but unlike Mr. Turkentine, whose world salad “doesn’t matter in the slightest,” Wonka’s point remains comprehensible.

Take, for example, Wonka’s introduction of the Oompa Loompas:

Violet Beauregarde: Well, they can't be real people.

Willy Wonka: Why, of course they're real people.

Mr. Salt: Stuff and nonsense!

Willy Wonka: No, Oompa Loompas.

The Group: Oompa Loompas?

Willy Wonka: From Loompaland.

Mrs. Teevee: Loompaland? There's no such place.

Willy Wonka: Excuse me, dear lady, but...

Mrs. Teevee: Mr. Wonka, I am a teacher of geography.

Willy Wonka: Oh, well, then you know all about it and what a terrible country it is. Nothing but desolate wastes and fierce beasts. And the poor little Oompa Loompas were so small and helpless, they would get gobbled up right and left. A Wangdoodle would eat ten of them for breakfast and think nothing of it. And so, I said, "Come and live with me in peace and safety, away from all the Wangdoodles, and Hornswogglers, and Snozzwangers, and rotten, Vermicious Knids."

Mr. Salt: Snozzwangers? Vermicious Knids? What kind of rubbish is that?

Willy Wonka: I'm sorry, but all questions *must* be submitted in writing.

Within the walls of his factory, Wonka successfully asserts himself the authority. His explanation of how Oompa Loompas came to his factory is peppered with wacky words like “Wangdoodle” and “Hornswogglers,” but the reasoning behind his decision couldn’t be more straightforward: “Come and live with me in peace and safety…”

Wonka has a way of speaking that is comprehensible to children but vexatious to adults, whose minds are cluttered by notions of geographical facts and limited by a reasonable understanding of the world around them. Wonka displays little patience for the parents, dismissing Mr. Salt with a demand that “all questions must be submitted in writing,” an unambiguous directive that, contextually, makes no sense. Before Mr. Salt can work through his befuddlement, Wonka is onto the next thing.

Mr. Salt: What is this, Wonka? Some kind of funhouse?

Willy Wonka: Why? Are you having fun?

Wilder’s Wonka, and the film he occupies, thinks more of its audience and their intellect. In the whimsical wonderland of Wonka’s creation, his brattish visitors are in mortal peril, a fact that Wilder’s Wonka breezes past with witticisms and delirious doublespeak.

Wonka is protective of the world he has constructed for himself and seeks an heir who will carry forth his eccentricity. Any of his guests who attempt to bring reality into Wonka’s world are met with hostility.

When he presents edible wallpaper to his guests, he entreats them to lick it, saying, “The strawberries taste like strawberries, and the snozzberries taste like snozzberries!”

Veruca spits back, “Snozzberries? Who ever heard of a snozzberry?”

Wonka grabs her face, holding her mouth open to stop her from speaking, and tells her, “We are the music makers, and we are the dreamers of dreams.”

Wonka is essentially telling Veruca, whose question threatens the fabric of Wonka’s meticulously constructed reality, “Hush child, we create our reality and in the factory I built, the Snozzberries taste like Snozzberries. Got it?”

There are no further questions.

“So shines a good deed in a weary world.”

After all the other children have been eliminated, Charlie is unceremoniously dismissed by Mr. Wonka, who retreats into his office. Grandpa Joe goes to speak with Wonka and inquire about the lifetime supply of chocolate promised to Charlie. Wonka’s response is explosive:

Grandpa Joe: The-the lifetime supply of chocolate, for Charlie. Wh-When does he get it?

Willy Wonka: He doesn't.

Grandpa Joe: Why not?

Willy Wonka: Because he broke the rules.

Grandpa Joe: What rules? We didn't see any rules, did we, Charlie?

Willy Wonka: Wrong, sir! Wrong!

Under section 37B of the contract signed by him, it states quite clearly that all offers shall become null and void if - and you can read it for yourself in this photostatic copy: I, the undersigned, shall forfeit all rights, privileges, and licenses herein and herein contained, et cetera, et cetera...

Fax mentis incendium gloria cultum, et cetera, et cetera... Memo bis punitor delicatum! It's all there, black and white, clear as crystal!

You stole fizzy lifting drinks! You bumped into the ceiling which now has to be washed and sterilized, so you get nothing! You lose! Good day, sir!

As he shouts terms from half a contract through half of a magnifying glass, it becomes clear that the embittered Wonka has become half a man. The once-fabled dreamer of dreams has been reduced to a stickler for fine print. The capitalist titan’s soul has been tarnished by his participation in a capitalist system built upon exploitation and competition. It has caused him to become paranoid, alienated, and cynical about human nature. In this moment, Wonka regards Charlie as a leech, just like the rest of them, looking for his payout in precious chocolate.

That’s why what Charlie does next stuns Wonka. Against the protestations of his Grandfather, who proposes selling the prized Everlasting Gobstopper to Slugworth to spite Wonka, Charlie leaves the candy behind. In forgoing corporate espionage, Charlie proves his pure intentions to Wonka and wins the right to be Wonka’s heir.

In Charlie’s moment of triumph, Willy Wonka reveals the impetus for his contest, which is also the source of his angst. There is one fact of life that Wonka cannot keep hide from, not even in a world entirely of his own making: Willy Wonka is facing his own mortality. He tells Charlie, “I can't go on forever, and I don't really want to try.”

Even while confronting his own mortality, Wilder’s Wonka works in a witticism. The ability to embody a one-of-a-kind comic character like Wonka so exuberantly, while also managing to believably tap into a universal source of vulnerability, angst, and fear is why Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory remains timeless and Gene Wilder will live forever.

Until next week, don’t eat too much candy, film freak.