“Taking offence, and making a show of it, is a peculiarly self-theatrical, melodramatic, histrionic gesture in the annals of criticism. It is an attractive gesture – attractive to a reading or listening audience, as well as flattering to the one who performs it – because it appears so proud, firm, strong and certain.”

-Adrian Martin in “The Offended Critic”

In 2022, two different filmmakers made two different movies that were, in essence about the same thing: “Old Hollywood.”

Both films are grandiose, self-indulgent affairs sporting three-hour runtimes. Both are critical of the industry which produced them. Both displayed commendable technical competence with regard to the formal elements of cinema. Both films are crass, bawdy, lewd, and at times, downright depraved. Finally, upon release, both films flopped.

Andrew Dominik’s Blonde, starring Ana de Armas as Marilyn Monroe, was released on Netflix in September of 2022 and quickly became the subject of critical backlash. A few months later Damien Chazelle’s Babylon, an extravaganza starring Margot Robbie and Brad Pitt, bombed at the box office.

I believe both films were conceptualized with noble intent: to depict, explore, and expose the dehumanizing nature of the film industry and the way it chews up people (particularly women) and spits them out.

Both films moved me but in vastly different ways. Throughout their extended runtimes, I was alternately seduced and repulsed. My affinity for each film waxed and waned in response to each subsequent creative decision.

They were interesting viewing experiences: one text ended up winning me over while the other deeply offended me — a fact that I found fascinating and which begs the question: what offended me and why?

“When you react to a movie, you react to the whole thing, its entire gestalt of form and content – and you react as fully you, body and mind, emotions and personal history combined. Everything that fits under the category of formal elements in a film, all the things sometimes wrongly considered as on top of or beneath the plot … trigger in us intense reactions of taste and distaste, tied to all the complex mechanisms of desire and defensiveness. This intensity is completely personal, and completely cultural, all at once; it is completely whimsical, and completely historical.”

-Adrian Martin in “The Offended Critic”

This week’s newsletter will consider Babylon, its explicit content, and why my personal sensibilities were not offended.

Babylon is currently streaming on Paramount+ and is available for rent or purchase.

“Old Hollywood” as the “Offensive Subject”

“It is argued that offense is, ultimately, a closed-minded response that projects onto the troublesome film and turns it, in psychoanalytic terms, into a “bad object”, the repository of all the difficult feelings and thoughts of which we thereby purge ourselves.”

-Adrian Martin in “The Offended Critic”

This comparative analysis accepts Martin’s psychoanalytic explanation of offense (i.e. offended viewers project their disgust onto the films which provoked them, labeling them offensive, “bad objects” that are, thus, unworthy of engagement). I do, however, take umbrage with Martin’s characterization of “offense” arising exclusively from a “closed-minded” response to a film. Fundamentally, I agree that a closed-minded approach to film is generally conducive to viewers being offended, but there are times when being offended is an appropriate response.

Ultimately, I think Adrian Martin would agree. His exploration of “the politics of offense” is far more nuanced than his initial language would suggest. He parlays his description of offense to offer another way of engaging with films.

“Another way of reacting to cinema is proposed: trying to stay open to ambivalence, enigma and contradiction, as well as the complexities of our own sensibilities as viewers.”

-Adrian Martin in “The Offended Critic”

Martin’s “alternative way to reacting to cinema” is one that I have already unconsciously adopted. Yet I still object to the reductive statement that offense arises exclusively out of “close-mindedness” because it invalidates the viewer’s subjectivity. It implicitly judges the viewer — to be offended is to be close-minded, and to be close-minded is a bad thing. As an individual, you are entitled to feel offended. While I will never know exactly what offends your sensibilities, I do not feel comfortable operating on the assumption that you are close-minded.

I also champion a more “open-minded” approach to film, but for a viewer to be offended they must have been open-minded enough to engage with the text. The mere existence of a film would not - or should not - offend you. If the mere existence of a film offends you, I am comfortable with Martin’s characterization of your offense as “closed-minded.”

I believe genuine offense can only be genuinely provoked when a viewer actively engages with a text that offends their personal sensibilities. Martin expounds upon the importance of “sensibility” when evaluating “the politics of offense.”

“Rather than reducing a film to a series of paltry tokens – characters, stereotypes, plot moves, messages – that are then ground through a grey mill of political adjudication, we can argue, politically, from sensibility and about sensibility. We do not have to fall back into that slightly elitist, literary trap of always stressing the subtle, artistic intention, the dramatic irony, the suggestive mood or the camouflaged, authorial point-of-view.

Sensibility takes in all that, but is also equally attuned to the immediate, surface, moment-to-moment level of sensation in a work, that “erotics of art” to which Susan Sontag advised us to attend on a level beyond and against interpretation. Sometimes, our gut reaction to a film – that overwhelming sense that something in it is intensely true, or irredeemably phony – is, in fact, a quite reasonable place from which to start (so long as it is not deployed as either an absolute or a show-stopper), since it arises from the whole personal and political formation I am calling a sensibility.”

-Adrian Martin in “The Offended Critic”

With the centrality of “sensibility” in mind, let us set aside the presumably noble intentions of each respective film. Let us acknowledge Babylon’s and Blonde’s drastic differences in presentation and content. These differences are precisely what our sensibilities respond to, but let us also recognize their overlapping focus: “Old Hollywood” and all the thematic baggage that notion carries with it.

“Old Hollywood” serves as the pretext through which audiences are confronted with upsetting truths with the potential to provoke offense. These films are not self-congratulatory, masturbatory celebrations of the wonders of cinema. They are aesthetically splendorous indictments. It’s the industry’s excess and abuse that provokes our offense. If these offensive films, by their nature, become “offending objects,” “old Hollywood” is the offending subject.

“Often, what a film is nominally about – the Vietnam war, street gangs, religious debates – is breezily dismissed as almost irrelevant, a mere pretext or handy, disguised metaphor for what the critic thinks the movie is really, deeply, often symptomatically or unconsciously about in its imaginary: very often, this is something related to sex, gender, or the institution of the nuclear family.”

-Adrian Martin in “The Offended Critic”

In defiance of previously espoused sensibilities, I’ll introduce each film with a trailer because I assume that you, my fellow film freak, have not spent six cumulative hours watching movies that flopped.

As far as trailers go, I think they’re pretty good. They offer a glimpse of what watching each respective film feels like without revealing much about the film itself.

(For more on the form and function of movie trailers, see “Trailer Trash and Treasures: The Art of Coming Attractions”)

Babylon: An Ode to Unsustainable Excess

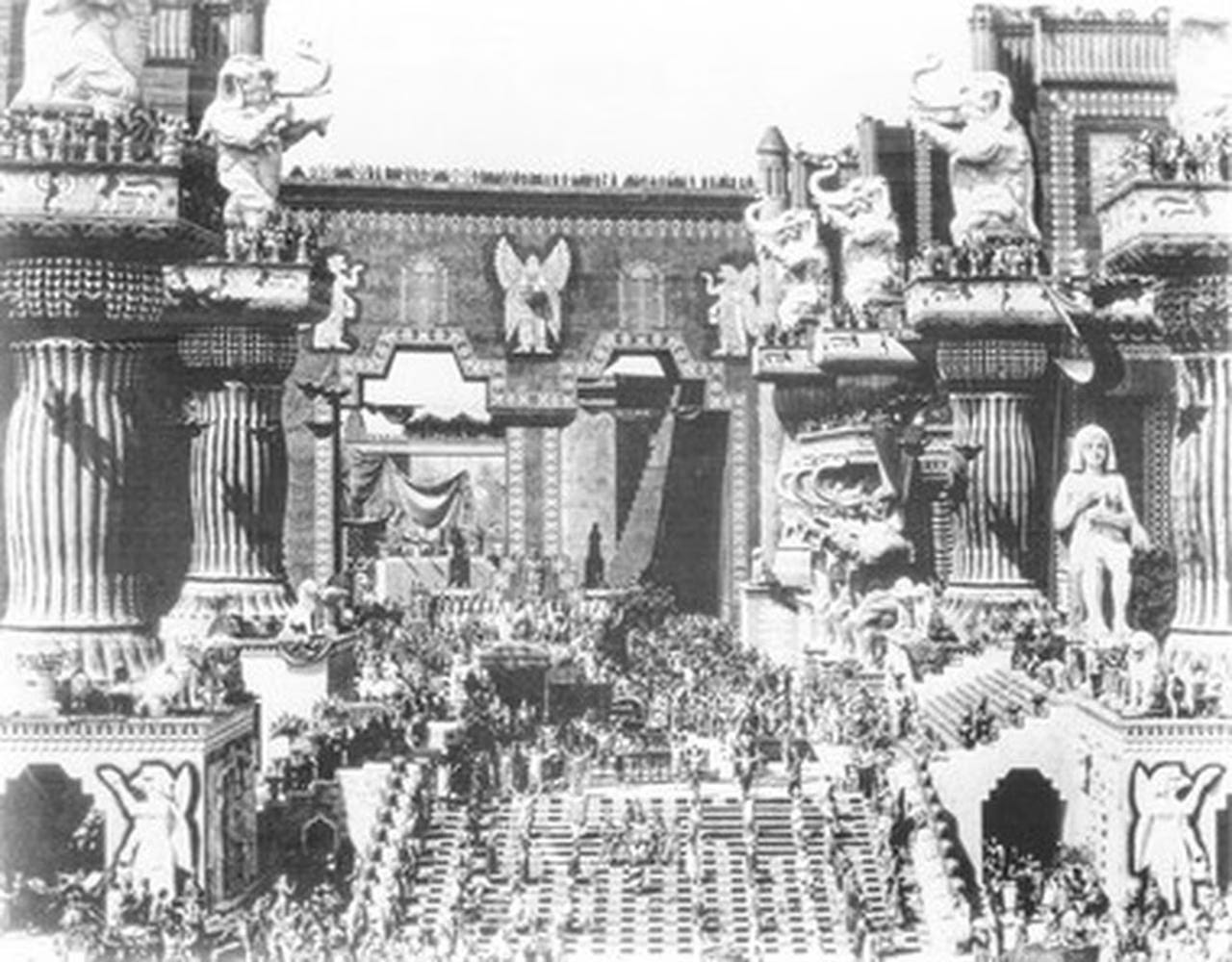

It’s difficult to glean much from this trailer, and that fact may have contributed to its failure at the box office. One does not know what to expect from Babylon except extravagant excess. The film’s plot and characters are, within this trailer, subsumed by a barrage of hedonistic depravity that flourished in silent-era Hollywood, before moral panic took hold and the implementation of the Hays Code ruined the fun.

Babylon begins in 1926 and follows a colorful cast of characters navigating the transition from silent films to “the talkies” and beyond.

It was fortuitous that I watched Babylon shortly after Tár, which I loved despite being too stupid to understand. With Babylon, the inverse felt true. My time studying film, its form, and historical development, left me feeling uniquely equipped to grapple with Babylon on its own terms. I can never know how Babylon would feel if I had not taken History of Global Cinema and been forced to endure the films of innovative cinematic racist, D.W. Griffith. My studies helped me spot countless references and homages to classic films.

I don’t mean to suggest that Babylon, behemoth though it may be, is inaccessible to more casual viewers. There’s ample spectacle, dark humor, and stellar performances for your viewing pleasure. Like Tár, viewers need not understand every piece of film-industry-related terminology. Cinematic gobbledegook doesn’t dominate dialogue in a way that will inhibit any viewer's ability to track the film, assuming that you are paying attention.

For every part of the film that caters to the snobbish cinephiles, there are moments that cater to the lowest-brow sensibilities. Mere minutes into the film, an elephant shits on two people in graphic detail. I find scatological humor uncompelling. Would the rest of Babylon be just as puerile?

Only in fits and starts, and in ways that feel motivated by the film’s broader intentions. Here is a film in which two Hollywood big-wigs talk in a public restroom. Jack (Brad Pitt), the most successful working actor, asks if the Hollywood executive is certain that audiences actually want sound in their films.

“Sure,” the executive says, “why wouldn’t they?”

His answer is punctuated by the loud sound of a man shitting in a nearby stall.

This moment, I admit, garnered a chuckle. The asinine joke, which I would normally find off-putting (not to be confused with outright offense) is tempered by a self-awareness that elevates the scene above toilet humor. Instead, the moment becomes a commentary on all the low-brow gags that cinematic sound will enable. Babylon is intellectually operating at a higher level than its vulgar humor would suggest.

Broadly speaking, Babylon employs vulgarity with intention. During a raucous party at the film’s opening, a young woman gives “a golden shower” to an obese man. He is positively giddy as urine flows into his mouth. I don’t find this moment offensive per se, it’s certainly offputting. In moments like this, I cannot help but wonder, “Why is this being shown to me?”

If that question has an answer — if I can understand the moment’s purpose — I’m far less likely to be offended. The presence of intention doesn’t mean other viewers won’t find the depravity offensive. However, this viewer’s sensibilities are appeased.

Well, the obese man is presumably a reference to Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, a successful silent-era comedian that was accused of rape and manslaughter in the death of actress Virginia Rappe. Babylon does not depict any sexual violence, nor does it strictly hew to the facts of the case. However, their bedroom piss play is possibly a reference to Rappe’s cause of death, a ruptured bladder. Police reportedly concluded that Arbuckle’s weight on Rappe’s body caused her bladder to burst. He was tried thrice. At the time, it was quite a scandal among the public.

Stories of salacious behavior prompted scrutiny and moral outrage. Eventually, faced with the prospect of censorship by Congress, the film industry self-regulated and forbade the depiction of offensive behavior via a set of rules known as The Hays Code.

In Babylon, the young woman dies of an overdose. Her death poses two problems: the body must be discretely removed from the premises and the actress was scheduled to shoot tomorrow. The young woman’s death is regarded as little more than an inconvenience but her unceremonious demise is what gives aspiring actress Nellie LaRoy (Margot Robbie) her big break.

I struggle to recall a film so explicitly interested in the intersection of high and low-brow sensibilities. At its core, Babylon expresses a wide-eyed passion for early cinema akin to that of Scorsese’s Hugo (2011) smeared with cocaine residue and body glitter a la Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street (2013).

So does Babylon consider film high or low art? Babylon’s answer is a firmly ambivalent “yes.” Consider the following:

Historically, cinema was entertainment for the masses and, as such, continually evolved alongside public sensibilities. Those unable to afford tickets to the theater could find affordable entertainment at the movies.

Society’s shifting moral demands prove troublesome for Nellie LaRoy, a bawdy actress with a gambling problem and a foul mouth. As Hollywood is subjected to censorship, LaRoy is required to clean up her act. The vulgar vigor which enabled her initial success now acts as a hindrance. If she is to have any future in the business, Nellie LaRoy must become a proper lady.

She walks a tightrope between a rock and a hard place in an industry that prizes her as a sexual object for viewers’ pleasure, nestled within a society that cannot tolerate a sexually liberated woman. Marilyn Monroe would be forced to walk the same tightrope decades later.

The advent of sound also poses a threat to LaRoy’s burgeoning career. The technical challenges of synch sound flummox LaRoy in a scene that pays homage to Lina Lamont's struggles in Singin’ in the Rain (1952), another film that centers on the advent of sound in cinema.

The cinematic form continues to evolve alongside the public’s sensibilities. Simultaneously, technical innovations allow filmmakers to create movie-going experiences that previous generations could not fathom. Amid the constant changes, individuals are unceremoniously tossed aside and the next generation of talent prepares to take their place. That will never change, a sentiment articulated with an incisive melancholy during a conversation between Jack and a gossip columnist in the film’s latter half. Certain realities remain intractable.

Babylon refuses to employ restraint as it makes its point. It uses its vulgarity to temporally orient the viewer, placing them at the precipice of a turning point in Hollywood. Amid change and upheaval in the industry, Babylon interrogates the constantly evolving form and function of cinema vis-à-vis its offensive content.

I cannot say whether you will be personally offended by Babylon. There is, no doubt, plenty to be offended by. I can only speak for myself and my sensibilities.

For me, Babylon’s saving grace is its self-awareness. Some parts enthralled me, others alienated me, but I never doubted that Chazelle understood his film’s potential to offend. It maintains no illusions in its more depraved moments, able to separate and celebrate the highs and lows of cinema.

For all the change movies have undergone, one cannot help but recognize the myriad ways in which the industry remains fundamentally unaltered — an offensive reality provoked by an offensive film that, ultimately, did not offend my sensibilities.

On the contrary, I was deeply moved by Babylon’s starry-eyed cynicism. It stands in stark contrast with Chazelle’s La La Land (2016), which offered a vision of contemporary Hollywood that is more romantic and sanitized.

The same cannot be said for Andrew Dominik’s Blonde, undoubtedly the most offensive film I saw in 2022, which will be the subject of next week’s newsletter.

I leave you with a teaser of the most offensive and fascinating failures in recent memory.

Thank you for your time and attention.

If you haven’t already, subscribe to Acquired Tastes for a newsletter delivered to your inbox every Sunday:

Or, if there are other film freaks that you know, please:

If you’ve seen Babylon, I’d love to know your thoughts. I’m also curious about which films you personally find offensive so please:

I look forward to seeing you next week, my fellow film freak.