This week, I want to take a step back from examining what we watch to consider the things that we watch to help us decide what to watch. Simply put, I want to talk about trailers.

Movie trailers and music videos have a lot in common. I consider their function analogous within their respective industries. They are, first and foremost, promotional materials. Yet I don’t think it’s controversial to claim music videos have developed as an art form. The existence of visual albums like Beyoncé’s Lemonade or Janelle Monáe’s criminally underrated Dirty Computer is concrete proof of their evolution. Music videos have become both promotional material and art.

So too, I would argue, are movie trailers. Trailers have evolved alongside cinema. Gone are trailers beginning with “In a world…”. Overwrought voice-over has fallen out of fashion. There is something quaint about the trailers of the 90s and early 2000s but when I’ve seen contemporary trailers cut in that style, it registers as odd, almost anachronistic. Movie trailers have evolved, for better or worse, into an art form all their own. Their cinematic form increasingly resembles that of music videos. So this week I want to explore the art of movie trailers: the particulars of their form, and how their form impacts their function.

Complaining about movie trailers is well-trodden ground. We all know the purpose of trailers is to market a film to prospective audiences. We can all agree that a trailer shouldn’t spoil a film. Ideally, the trailer will pique a viewer’s curiosity without spoonfeeding them the entire plot.

As I expound upon my own sensibilities I also want to survey you, my dear reader, to know what you think. Each trailer will be followed by a poll asking: “is this an effective trailer?” The considerations and criteria that inform your response are entirely your own, and I welcome perspectives that conflict with my personal sensibilities. Each poll will be a simple “yes” or “no,” and I hope you will participate.

A Tale of Two Trailers

I recently went to see Cocaine Bear, a film that dominated the cinematic zeitgeist of February 2023. I never watched a trailer. The film’s title was enough to capture my attention. I entered the theater knowing the following: Cocaine Bear is directed by Elizabeth Banks and is inspired by the (highly exaggerated) true story of a bear that ate cocaine. That’s all. I prefer to enter a movie with nothing more than a nebulous word cloud of factoids about whatever I’m going to see: its director, genre, maybe the cast, and basic premise.

Before Cocaine Bear’s rampage began, I saw two coming attractions. The first was for Scream VI. I grumbled as soon as I saw Ghostface.

Being the sixth iteration of an intellectual property that I am already a fan of, I don’t want or need a trailer to entice me to see Scream VI. I’m already sold. Scream films are, at their core, meta-whodunnit slashers. Their appeal relies on its ability to surprise audiences. A hamfisted trailer only serves to dilute the film’s impact.

Turns out it wasn’t a trailer, it was a blissfully brief teaser that conveyed only essential information: Scream VI will take place in New York City.

Then came a red band trailer for Strays, a forthcoming “hard-R” comedy.

Red band trailers contain explicit material that wouldn’t be considered appropriate for general audiences. In the case of Strays, profanity constitutes most of the trailer’s offensive content.

In my opinion, this trailer, clocking in at two and a half minutes, uses the “red band” label to indulge the worst tendencies a trailer can exhibit. It offers the film’s plot, characters, plot twist (i.e. the quest to “bite Doug’s dick off”), and every comic premise the film has in its arsenal (e.g. dogs getting drunk, humping things, getting carried away by birds, tripping on mushrooms, etc.). Trailers of this ilk plague the comedy genre, so eager to convey hilarity to prospective viewers, and the red band label exacerbates this troubling tendency.

For now, let’s put a pin in the “red-band” trailer.

Movie Trailer’s Form and Function

My relationship with movie trailers is one defined by ambivalence. I go out of my way to avoid them prior to seeing a film. Entering a theater with a blank slate allows the film the opportunity to surprise me, a rare but treasured experience for this jaded cinephile.

On the flip side, I love the art of movie trailers. After seeing a film, I will watch the trailer. Having already “purchased the product,” I’m curious how a studio is trying to sell me that which I have already “bought.”

Most trailers run afoul of my sensibilities: misleading, spoiling, or otherwise tainting the advertised cinematic experience. There are, however, “good” trailers. Over the years I have curated a playlist of “good” trailers. I revisit them often, whenever I want a taste of a movie but don’t have time to sit for the film’s entire runtime.

A “good” trailer is an “effective” trailer: it satisfies its marketing function and passes a subjective assessment of quality, rooted in personal taste and sensibilities. I would argue that an “effective” trailer conveys how a movie feels without revealing much about the film itself.

For transparency, these are some of the questions I consider whenever I watch a trailer: Does this trailer make me want to see the film? Is it “effective?” What makes a trailer effective?

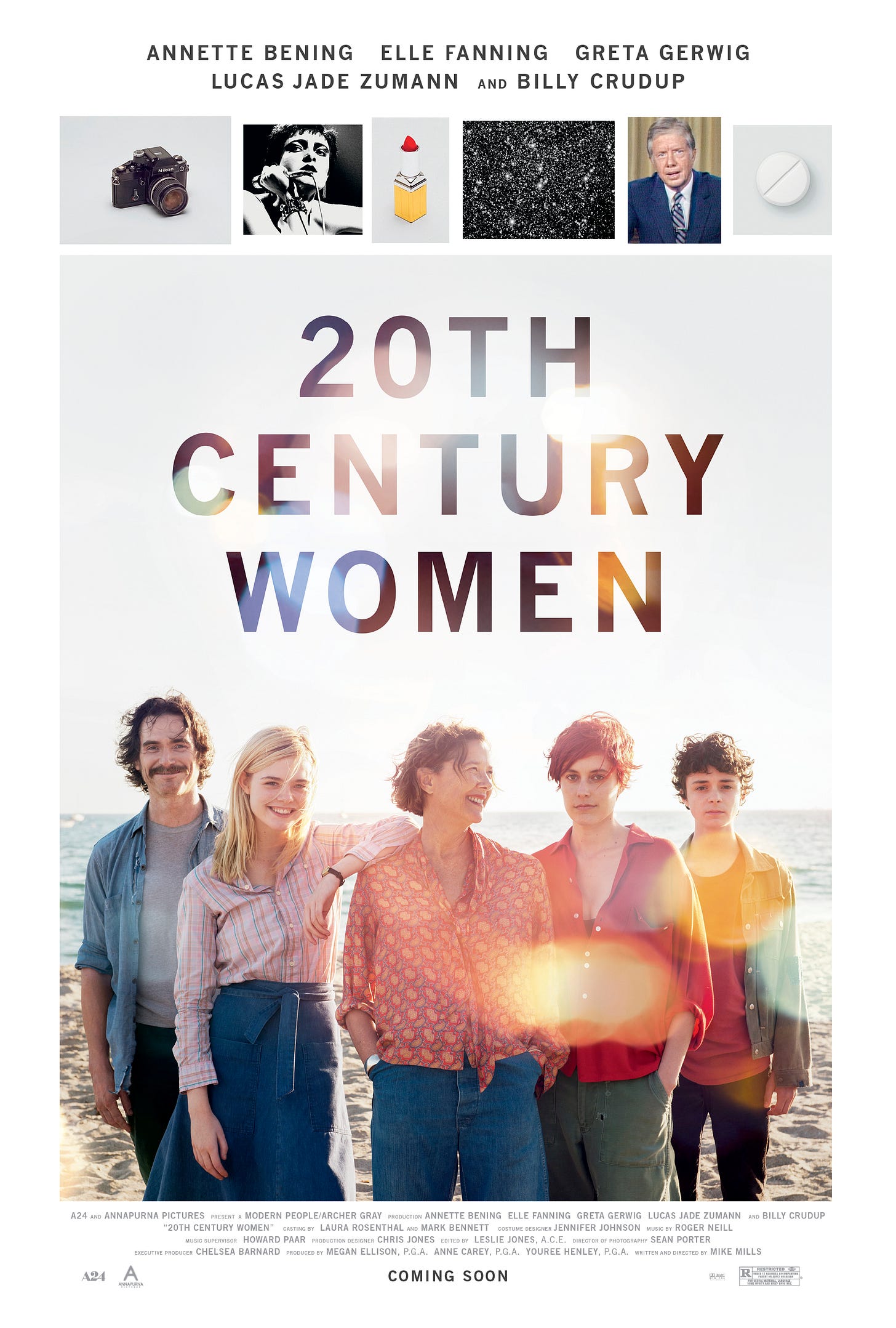

Let’s begin with a trailer for 20th Century Women (2017), which happens to be my favorite film.

Setting aside the fact that this is my favorite film, I think that this is an effective trailer. It immediately introduces the film’s setting and key fascets of cinematic language which the film will repeatedly employ: a soothing score, intellectual montage, and omniscient voice-over.

Annette Benning’s opening voiceover conveys a lot: a mother’s warm, tender love (“When you were born I told you life was very big and unknown. There were animals, cities, and music…”); her hopes for her child’s future (“You’d fall in love, have passions, have meaning…”; and the acute challenges she now faces (“… But now it’s 1979 and nothing means anything, and I know you less every day”).

Upbeat music shifts the trailer’s tone and we are presented with the film’s central question, “How do you raise a good man? What does that even mean nowadays?” A series of visuals relays the film’s aesthetic, with cuts motivated by musical cues. Snippets of dialogue provide insight into the film’s tone and thematic material without divulging any plot points. Sometimes they are funny (“Having a kid seems like the hardest thing.” “How much you love the kid, you’re just pretty much screwed.”), sometimes they are poignant (“You get to see him out in the world, as a person. I never will.)

Quick cuts, synced to music, create a montage of images whose rhythm builds to the trailer’s climax: the movie’s star-studded cast. Another moment of poignant voiceover acts as the trailer’s denouement. Then comes the film’s title card followed by a “button,” a final snippet of comic dialogue that will, hopefully, leave audiences smiling.

Within this trailer is a blueprint that offers insight into my sensibilities concerning the art of trailers. The “music-videoesque,” montage approach to editing trailers can transcend genres and span taste high and low.

Consider this trailer for Birds of Prey (and the Fantabulous Emancipation of One Harley Quinn):

This trailer is built around "Hyme à l'amour" by Edith Piaf, a song you wouldn’t expect in a superhero movie trailer. Then again, Birds of Prey isn’t like most comic book films. It’s a break-up film. It’s a joyous, feminist looney tune fueled by cocaine and glitter. In that way, the trailer’s unconventional music perfectly suits this oddball film.

Dialogue punctuates "Hyme à l'amour," and the characters’ words become an integrated extension of the music. The trailer comes together like a symphony, hinting at the movie’s themes but leaving its plot obscured. Shots and clips from the film are selectively pulled, without regard for narrative continuity, and stitched together in a flashy, discontinuous style that fractures the film’s narrative but communicates the movie’s vibe.

At their best, trailers are not fixated on characters or narrative. Rather, they are selling a vibe, a mood, a sense of what watching the movie feels like.

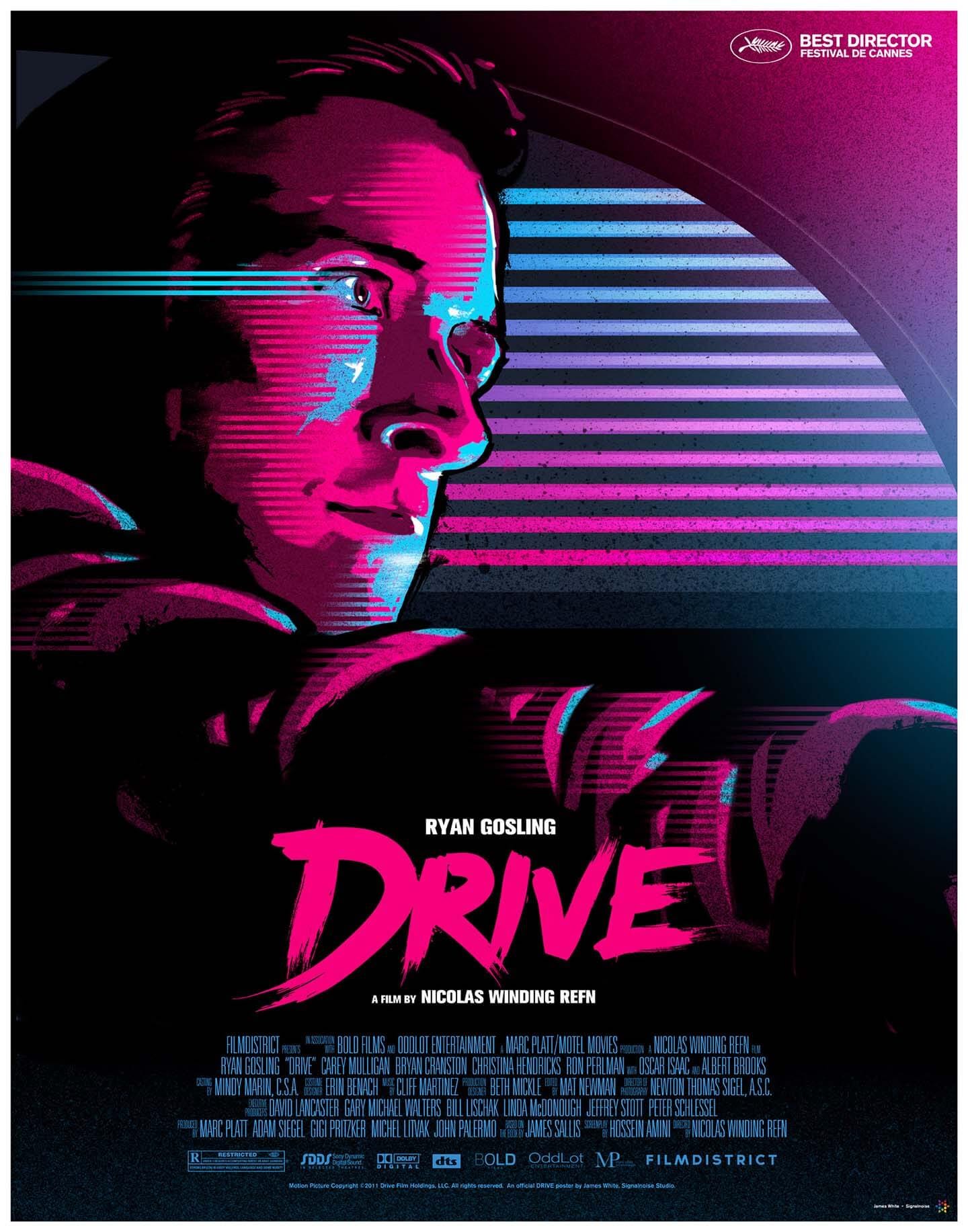

When a movie is mismarketed, it’s usually because a studio cut a deceptive trailer that elides the movie’s true essence in favor of something more boilerplate, familiar to audiences. The trailer for Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive (2011), comes to mind.

Drive is a stunning film, but the neo-noir fairy tale was marketed as if it were a Fast & Furious film, obfuscating the character-driven nature of this slowly-paced film. Upon the film’s release, the trailer's shenanigans were obvious. Some portion of the audience was pleasantly surprised by the higher-brow cinematic experience. The rest had been duped into buying tickets to a film whose trailer seemed to promise non-stop, thrilling action. The studio got their money and the film is far better than the trailer would suggest, but I regard the tactic as cinematic malpractice.

Returning to the “Red Band” Trailer

Let’s unpin the red band trailer and consider how it is employed. Red band trailers are only approved for certain audiences. They may include profanity, sexuality, or violence that goes beyond the boundaries of conventional advertising. In theory, trailers of this ilk offer prospective audiences greater insight into a film’s thematic content and presentation.

The red band trailer for Strays uses the freedoms of the red band label to flaunt its outrageous humor. A sampling of profanity is warranted in Strays’ case. Unfortunately, as is too often the case, the trailer refuses to quit while it’s ahead. The marketing team is so desperate to convince audiences of the film’s hilarity, it reveals all the jokes up its sleeve. These are red band trailers at their worst, woefully misunderstanding their power and purpose.

Then there’s the trailer for Assassination Nation (2018), a lurid and provocative film from writer/director Sam Levinson, who would go on to create HBO’s Euphoria.

There is a “green band” trailer for Assassination Nation, but the “red band” trailer provides a more honest depiction of the film’s disturbing content and aesthetic presentation. Assassination Nation is a film I personally enjoy, but it is emphatically not for everyone. The red band trailer, and the explicit content it depicts, provides a far more accurate picture of what watching Assassination Nation feels like (without languishing in its depravity like Strays). This is a violent and disturbing film with the potential to upset audiences. It’s also a hell of a ride for those with a strong enough stomach.

By way of warning, this trailer’s caption reads: “Red Band Trailer. Safe for work — Not safe for school, parents, or the easily offended.”

Watching this trailer may dissuade you from watching the film and, in doing so, exemplifies an underutilized function of red band trailers. Red band trailers offer marketing teams the opportunity for increased transparency with audiences, something approximating “truth in advertising.” The questions, “is this an effective trailer?” and “Does watching this trailer make me want to see the film?” may, in some cases, become divergent considerations. It probably registers as counterintuitive from a business perspective, insofar as the goal of trailers is to sell tickets, but I think red band trailers of this sort are among the most effective, useful coming attractions. An effective trailer is an honest trailer. For every person keen to see Assassination Nation, there is a handful who will opt not to. This is for the best. The trailer has done its job, encapsulating the films polarizing nature, and it does in style.

It is a work of art.

Thank you for your time, attention, and participation.

See you next week, my fellow film freak.

Or, if there are other film freaks that you know, please: