Tim Burton’s Planet of the Apes ⭐️⭐️

After a twenty-eight-year hiatus, Planet of the Apes returned to the big screen in 2001, directed by Tim Burton. I must admit up front that I’m a big fan of his work, but there’s no denying that Burton’s filmography is… uneven.

His best works have a dark, distinctive gothic luster (e.g. Beetlejuice (1988), Batman (1989), Edward Scissorhands (1990)). There are works of unabashed weirdness, especially towards the beginning of his career, that blossom from pre-existing intellectual properties or historical figures (e.g., Pee Wee’s Big Adventure (1985), Batman Returns (1992), Ed Wood (1994)).

If you fast forward to the 2010s, you’ll notice something about Burton’s filmography has shifted. Alice in Wonderland (2010) is a narrative and visual abomination, Dark Shadows (2012) is a total dud, and a Disney automaton might as well have directed Dumbo (2019).

When did it all go awry? His output in the late 90s was as weird (viz. Mars Attacks! (1996)) and gothic (viz. Sleepy Hollow (1999)) as ever. If you ask me, Burton’s films began to stray from their singular style and thematic oddity in the new millennium, starting with the schlockbuster remake of the 1968 sci-fi classic, Planet of the Apes.

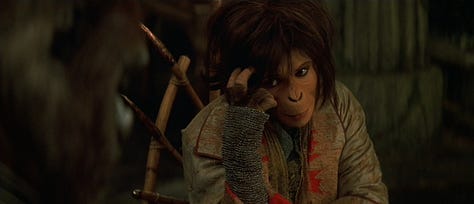

Burton’s Planet of the Apes is a visually impressive production that operates without the technological and budgetary constraints of the original series of films. The photorealistic make-up effects on male apes exemplify movie magic at its finest, but inexplicable creative choices, like altering the design of female apes to comport with human beauty standards, exemplify Burton’s most misguided instincts.

However, the film’s visual splendor and embarrassing blunders belie the fact that Burton’s “remake” fundamentally misunderstands or entirely disregards the defining characteristics of its source material.

As Part I of this retrospective mentioned, I’m not enamored with Planet of the Apes (1968). Its pacing is slow, its themes are numerous and overlapping, and it heavily relies on dialogue over action to advance its story. However, for all its shortcomings, I admire the original film’s use of the science fiction genre to explore sociopolitical issues intertwined with current events circa 1968. Even the vastly inferior sequels attempted to grapple with issues surrounding faith, science, law, race, morality, and humanity’s destructive nature.

This remake opts not to use the sci-fi genre to do any of that. These apes aren’t like the “boring” ones in the original film, philosophizing about dreadfully boring big ideas. These apes are violent and “cooler.”

“Ape shall never kill ape,” the central moral distinction that separates Ape society from humanity in the original series, is entirely absent. Here, the Apes’ moral high ground is abandoned, and the most sacred rule of The Sacred Scrolls is transgressed with no ramifications because on the Planet of the Apes circa 2001, violence has no moral value attached to it. There is no mention of Sacred Scrolls or established moral structure in Ape society. As a result, violence isn’t a shocking taboo; it’s a glorious spectacle! There are no rules on Burton’s Planet of the Apes, no meaning, and absolutely no soul.

New Millenium, No Rules

Our story begins in 2029 aboard the USAF Oberon. Captain Leo Davis (Mark Wahlberg) is training his chimpanzee crew mate, Pericles, to land a spaceship in a flight simulator.

Leo Davis and his crew spot an anomaly in space. Against Leo’s wishes, Pericles is sent into the wormhole. The crew loses contact with Pericles, so Leo launches a spacecraft to follow Pericles in defiance of his crew. You might say that Leo is a loose cannon that doesn’t play by the rules, and you would be right.

Leo and Pericles remain separated, and Leo crashes onto an unknown planet. There, he finds — you guessed it — sentient apes hunting humans in primitive garb.

In a departure from series lore, humans still have the capacity to speak. Regardless, apes maintain the evolutionary advantage and make light work of enslaving Leo and the pseudo-primitive humans. They are put into a cage on the back of a human-drawn carriage and are taken to Ape City.

In the city, they meet Limbo (Paul Giamatti), a slave trader whom the film regards as cheeky. General Thade (Tim Roth) arrives to inspect the captured humans. Limbo and Thade have a lighthearted, ostensibly comic discussion of humans and “the human rights faction.”

LIMBO: These the ones raiding the orchards, sir? I know an old country remedy that never fails. Gut one and string the carcass up ...

THADE: The human rights faction is already nipping at my heels.

LIMBO: Do-gooders. Who needs them? I'm all for free speech... as long as they keep their mouths shut.

THADE: I promised my niece a pet for her birthday.

LIMBO: Excellent. The little ones make wonderful pets... but make sure you get rid of it by puberty. If there's one thing you don't want in your house it's a human teenager.

As Limbo brands his new slaves, Ari (Helena Bonham Carter), a senator’s daughter and ardent human sympathizer, steals his hot iron. Ari purchases Leo and Daena (Estella Warren), an attractive blonde with no personality, to work in her father’s home.

That evening, Senator Sandar hosts a dinner for General Thade, who, it turns out, has the hots for the Senator’s daughter. Ari, of course, wants nothing to do with Thade. There is a brief discussion that hints at a conflict between politicians in the Senate and General Thade’s military tactics:

SANDAR: You are too long a stranger in our house.

THADE: My apologies, Senator. I stopped to see my father.

SANDAR: How is my old friend doing?

THADE: I'm afraid he's slipping. I wish I could spend more time with him... but these are troubled times. Humans infest the provinces...

ARI: Because our cities encroach on their habitat.

THADE: They breed quickly while we grow soft with our affluence. Even now they outnumber us ten to one.

NOVA: Why can't the government simply sterilize them all?

NADO: The cost would be prohibitive. ... Although our scientists do tell me the humans carry terrible diseases.

ARI: How would we know? The army burns the bodies before they can be examined.

SANDAR: At times, perhaps, the senate feels the army has been a tad... extreme ...

THADE: Extremism in defense of Apes is no vice.

That’s as political as the film gets. There is no further discussion of government, law, faith, or anything of substance for the rest of the film. Thade’s comment about defending “extremism in defense of Apes” evokes statements from the Bush administration post-9/11. If you swap “Apes” for “America,” you’re left with something Dick Cheney would undoubtedly say. However, the film was released months before 9/11, so any resonance is coincidental.

Leo picks the lock on his cage and escapes with his non-distinct fellow humans. Meanwhile, Thade is led by two scouts to the site of Leo’s crash landing. Now aware of an outsider among the humans, Thade rewards his loyal troops by slaughtering them.

Ari recruits Leo to join the human rebellion. The group sets out for Calima, a holy site in the forbidden desert. Thade’s troops pursue them. Chase scenes occur, padding the runtime with the illusion of action progressing the plot.

It turns out that Calima, the birthplace of an Ape uprising led by an Ape named Semos, is the wreckage of the USAF Oberon. The crew’s video logs explain that the Oberon attempted to follow Leo into the wormhole. Unfortunately, they were separated in time. The Oberon crashed thousands of years before Leo arrived.

It turns out Calima is derived from a partially obscured sign that reads, “CAution! LIve aniMAls.” CALIMA… get it? It turns out that the Oberon’s “chromosomally enhanced” animals led a rebellion against the Oberon’s crew, resulting in the advancement of Ape society. General Thade’s army arrives at Calima for an “epic showdown” that signals we’ve entered the third act, praise Semos.

It's Pericles, the monkey that Leo followed into the wormhole. His arrival could not be more perfectly timed. Mistaking Pericles for the second coming of Semos, Thade's army bows to their Messiah.

Let’s take a moment to consider the galling stupidity of this development. Up to this point, Semos and the Ape religion have never been explored in depth. At the pivotal moment, Pericles plops down from the rift in space and time. As if the timing alone were not absurd enough, he is instantly accepted as the second coming of Semos. All bow before him. But why? Nothing indicates Semos preached non-violence or peaceful coexistence.

On the contrary, all we know is that Semos led an uprising against the Oberon’s human crew. He is a historical figure known for using violence. Today, however, he has changed the hearts and minds of Apes who, moments before, were fully committed to slaughtering all humans.

Thade, a practitioner of violence, is unmoved by the second coming of Semos. Inside the Calima, Thade tries to kill Leo and the monkey Messiah in a sequence that includes my favorite moment in the whole movie.

Thade is bested when he is sealed behind an invisible, impenetrable barrier. He shoots a laser gun at the wall in vain, but the shots ricochet off walls until Thade is left cowering under a desk. I’m unsure what happens next to General Thade, but he’s hiding like a wimp, so consider him dunzo!

Things are wrapping up in the most convenient fashion. Leo and Ari take a moment to mourn the dead, but the film’s embrace of unfettered violence negates the impact of the intended emotional beats. Take, for example, the gorilla ex-general Krull. He used to serve under General Thade but had a falling out over the mistreatment of humans. Now, he serves as Ari’s bodyguard and ally in the fight for human rights. Krull’s protégé, Attar, has taken Krull’s place in Thade’s army. Krull and Attar meet on the battlefield and, amidst the chaos, fight to the death. Krull is bested in combat and dies, but honestly, there’s so much shit happening in that battle sequence that I barely noticed his death.

Assuming I did notice that Krull died, why would I shed a tear? He is just one of the film’s numerous unremarkable characters. His death means as much to me as his life did, which isn’t very much at all due to lackluster characterization. So, when the film revisits his burial, it feels emotionally insignificant. My apathy is further amplified by the fact that his grave will be unmarked “so that humans and apes will be mourned as one.”

It’s a seemingly nice sentiment that, in actuality, glosses over the critical divisions that caused this bloody conflict. Twenty minutes ago, it was mortal combat. Now, the problem has been solved. No need for further reflection. The slate is too easily wiped clean.

Considering the franchise’s historical relationship to race, and the ways slavery is depicted in this film, the eagerness to whitewash the film’s conflict feels problematic. It reeks of the insidious delusion of a “post-racial” society that was perpetuated in the early 2000s.

Independent of that broader context, the moment still erases the individuality of those who died in battle, and that does a disservice to the fallen. Violence and death are normalized such that Krull’s death and life mean nothing. Krull and his scruples are left to rot in a sandy, unmarked grave alongside every other individual whose life was snuffed out in the film’s senseless conflict.

Luckily, the massive cost of life is offset by the sudden and permanent end of all animosity between apes and humans. Praise Semos!

Continuing the streak of good luck that only terrible writers could conjure, Pericles has provided Leo with an operational spacecraft that can be used to return to Earth. Ari asks Leo to stay, but he declines. Instead, he climbs into the spaceship and lifts off, abandoning Pericles.

To call this film a thematic clusterfuck would be an understatement. Planet of the Apes (1968) and Planet of the Apes (2001) have nothing in common except that Apes rule a planet, and it’s not even the same fucking planet. The original film ended with the shocking realization that the Planet of the Apes was a post-apocalyptic Earth all along. According to IMDB, the remake takes place on a planet called Ashlar in the year 5021. I don’t believe this is mentioned within the film. If it was, I missed it.

Tim Burton’s Planet of the Apes is a big-budget disaster devoid of heart, brains, and soul. However, it was a financial success, earning $362 million off a $100 million budget. Unfortunately, it flopped with critics.

Does Burton’s Planet of the Apes do the franchise justice? No. Independent from the existing franchise, is it a good movie? No, but it is a movie with engaging visuals. Is it worth two hours of your time? Certainly not.

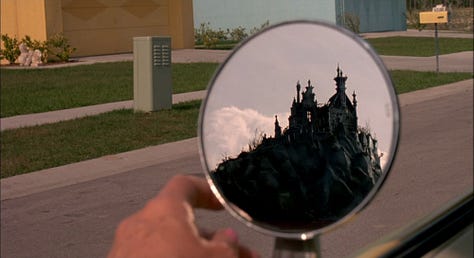

However, the film’s final moments are a brand of bat-shit crazy that feeds my soul. Leo emerges from his spacecraft and climbs the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Nothing can prepare him for what awaits.

Behind the statues is an inscription that reads:

“IN THIS TEMPLE, AS IN THE HEARTS OF THE APES FOR WHOM HE SAVED THE PLANET, THE MEMORY OF GENERAL THADE IS ENSHRINED FOREVER.”

What could this mean? How could this have happened? We’ll never know, and maybe that’s for the best. It is an ending so abrupt and strange it rivals the destruction of Earth at the end of Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970). An unhinged creative decision is a perfect way to end this bizarre shit-heap of a film.

Planet of the Apes would disappear for another decade. In 2011, Rise of the Planet of the Apes would reboot the series again, with more success.

Next week, in the final installment of Acquired Tastes’ Planet of the Apes Retrospective, we will consider the four contemporary Planet of the Apes films, including the recently released Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes (2024), less comprehensively. These films build upon the franchise’s legacy in intelligent ways but are strong enough to stand alone as the definitive Planet of the Apes films—for now, at least.

Until next week, keep an eye out for the Messiah's second coming, film freaks.

I am a fan of the series. A childhood treasure. Reading your reviews has shined a revealing, discerning, potent, well thought out and even comical perspective that demonstrates the “treasure” was an illusion framed from my eyes of youthful simplicity. I enjoyed watching the series with innocence for mere entertainment. Reading your review, I am thinking, “I did not see this, know or notice this.” Your higher analysis is educational. Thank you. Who knew there was so much to actually see?!!