The (Queer) Horror Paradox

“Gay people have a lot of emotional baggage so gay people need [horror] to kinda blow off steam. I think that’s what it is.”

-Trixie Mattel, teaching the children.

Queer identity is not a monolith. There is no “right way” to be gay. There are, however, a few things that I’ve noticed queer people tend to have in common. They include:

A propensity for walking fast.

An affinity for iced coffee.

An aversion to driving automobiles.

Poor navigational skills.

Interest in horror movies.

These stereotypes aren’t universal. I, for one, don’t like iced coffee. Resonating with one or more of these sentiments doesn’t mean you’re queer. However, if you identify as queer, I’m willing to bet that at least one of the above sentiments resonates. Sorta like the square-rhombus paradigm.

The appeal of horror is paradoxical. Why, you might ask, would someone willingly subject themselves to a horror film, provoking negative emotions like terror? To horror-averse film freaks, the pleasures of the horror genre may register as strange and slightly sadistic.

There is plenty of scholarship that examines the counterintuitive appeal of horror, which I intend to explore in depth come October. In June, Pride Month, I’m keen to approach the horror genre from a queer perspective.

“The Boogeyman” by Stephen King

The closet door was open. Not much. just a crack. But I knew I left it shut….”

-“The Boogeyman” by Stephen King

Before I went to see The Boogeyman (2023), I read the Stephen King story which inspired the film. It’s a short story, only thirteen pages. It tells the story of Lester Billings, a deeply troubled man, recounting his experiences with the Boogeyman to an unsuspecting psychologist, Dr. Harper. Billings is the father of three children, all deceased, purportedly at the hands of The Boogeyman. His story is his unraveling, a reckoning with his own failures as a man, husband, and father.

I am a fan of Stephen King’s work, and I’ve noticed he often draws inspiration from his own life. This particular short story seems rooted in the emotional challenges of sleep training a toddler as a new father. As we all know, small children often harbor a fear of the dark and cry out to their parents for comfort. One approach to sleep training, the Ferber method, encourages parents to let their baby cry at night until they learn to self-soothe.

The way Lester talks about parenting reveals a lot about his character. He’s a stern, masculine patriarch that lacks empathy and refuses to capitulate to childish fears like “The Boogeyman.”

“…that's the way kids start off bad. You get permissive with them, spoil them. Then they break your heart. Get some girl knocked up, you know, or start shooting dope. Or they get to be sissies. Can you imagine waking up some morning and finding your kid—your son—is a sissy…

“After a while, though, when he didn't stop, I started putting him to bed myself. And if he didn't stop crying I'd give him a whack… If a kid doesn’t get over being afraid of the dark when he’s little, he never gets over it.”

-“The Boogeyman” by Stephen King

Alas, none of Lester’s children survive long enough to disappoint him in this regard. In refusing to acknowledge the monster lurking in the closet, Lester makes the same mistake thrice, blinded by his refusal to acknowledge a threat beyond reasonable comprehension. Recounting his story on Dr. Harper’s couch, it’s clear that Lester Billings refuses to confront the monster in the closet. Billings is at the end of his rope and isn’t exactly a reliable narrator. It’s possible that the monster never existed. It’s possible that Lester is the monster.

“Are you backing away from something, Mr. Billings?”

-“The Boogeyman” by Stephen King

Being a “normal” child

When I think back to my own childhood, fear is the predominant emotion. Every night, around 7 pm, a heavy dread would materialize like a lead vest. A sense of doom lurked behind every door. Terror turned my stomach into knots. I couldn’t feel safe, and no amount of reassurance from my parents could soothe me.

I spent many years grappling with the manifestations of my fear without ever managing to get to the root of my terror. The stranglehold that fear had on my childhood was complex and multi-causal. However, in retrospect, I’m quite certain that the horrifying creature lurking in my closet was a part of myself that I refused to accept.

The fact that I was gay— which I realized very young but refused to accept for many years— scared the ever-loving shit out of me. I was the monster, and I denied my own existence.

If anyone found out my darkest secret, I wouldn’t ever be “normal” again. I’d be different, a “faggot” subjected to derision and ostracism. Certainly, my “normal” childhood, defined by omnipresent unease, was the lesser of two evils.

Terrified children make the darndest decisions.

When the Obergefell v. Hodges decision was announced on my birthday, I interpreted that as a sign. I came out that year, late in high school. It was the first step on a long road towards self-acceptance that, in theory, will lead me to some semblance of “pride.”

It was also around that time that I began reading Stephen King’s work. His work was my first major foray into fear. His writing is ugly, arguably pulpy, and tinged with gleeful malice. I was drawn to his work like a moth to a flame in a pitch-dark room, and his work proved to be a formative influence on my taste and sensibilities.

King doesn’t fear the dark, it’s where he thrives. He has a knack for externalizing fearsome evil via his monsters, putrid reflections of the most rotten facets of human nature. Negative emotions are channeled into grotesque monsters that pull on the darkest strings of the human imagination.

“One morning I got up and found a trail of mud and filth across the hall between the coat closet and the front door. Was it going out? Coming in? I don't know! Before Jesus, I just don't know! Records all scratched up and covered with slime, mirrors broken . . . and the sounds . . . the sounds . . .”

-“The Boogeyman” by Stephen King

The monstrous manifestations force King’s characters to confront fear incarnate. Or, in the case of “The Boogeyman,” a character’s refusal to do so. Sometimes evil is overcome and sometimes it subsumes our heroes. Lester Billings’ story ends in grim ambiguity.

I would be lying if I said I didn’t sympathize with his plight, due in large part to my own refusal to confront the monster in my own closet. Setting that aside, King’s writing has strong affective potential owing to the fact that he understands the internal experience of fear as well as he can externalize it.

“'You'd wake up at three in the morning and look into the dark and at first you'd say, ‘It's only the clock.’ But underneath it you could hear something moving in a stealthy way. But not too stealthy, because it wanted you to hear it. A slimy sliding sound like something from the kitchen drain. Or a clicking sound, like claws being dragged lightly over the staircase banister. And you'd close your eyes, knowing that hearing it was bad, but if you saw it . . . “And always you'd be afraid that the noises might stop for a little while, and then there would be a laugh right over your face and a breath of air like stale cabbage on your face, and then hands on your throat.”

-“The Boogeyman” by Stephen King

That passage took me back to the endless nights in my childhood bedroom. Every sound warned of an encroaching threat. As a helpless child, I was no match for whatever lurked in the darkness. The best I could do was pretend I was asleep, with the hope that whatever entered my room would opt to spare me another night. To acknowledge the monster in the closet would invite it to pounce. For years I remained frozen in fear, committed to denial.

From Page to Screen

In the 2023 cinematic adaptation of The Boogeyman, the story’s concept is mapped onto the standard screenplay structure of Syd Field’s Paradigm. Grafting a 13-page story onto this rote narrative structure produces less than inspiring results.

The story’s perspective shifts from Lester Billings to the therapist, Dr. Harper (Chris Messina). Following the death of his wife, Dr. Harper struggles to raise his two daughters while refusing to confront his grief. In keeping with many of King’s creatures, The Boogeyman feeds on negative emotion. For example, in It, Pennywise the Dancing Clown feeds on fear and hate. The Boogeyman feeds on grief.

The Boogeyman as a metaphor for grief functions thematically, but themes of loss and grief are explored in an inartful way. In one scene, a bully mocks our teenage protagonist for not having moved on from her mom’s death. It lacks tact, and the one-dimensional pathos does a disservice to its titular monster. On the page, The Boogeyman’s meaning was fluid. It imparts the idea that you, the reader, have a boogeyman. It is the lack of specificity that allows the premise to resonate more broadly.

In narrowing its thematic focus for the silver screen, a lot of the most interesting nuances of the horror story are lost. What remains is a serviceable PG-13 horror flick, a bloodless exercise in jump-scares with a monstrous creature that isn’t likely to stick with you after the credits, let alone haunt you at home. The creature’s design is like a fusion between the monsters from A Quiet Place and a spider. In refocusing almost exclusively on grief, the idea of fear itself becomes less salient, and, simultaneously, the film’s potential to induce fear is diminished.

The Boogeyman’s generic components and lukewarm critical reception led to a disappointing box office showing. The film had a budget of $35 million, which doesn’t include the extensive marketing budget leading up to the film’s release. To date, the film has grossed just over $50 million worldwide.

The Babadook (2014)

“If it's in a word, or it's in a look

You can't get rid of the Babadook.

If you really are a clever one

And you know what it is to see

Then you can make friends with a special one.

A friend to you and me.”

-“Mister Babadook” by Jennifer Kent

The Babadook, written and directed by Jennifer Kent, is a South-Australian horror film that has fueled nightmares all across the world. Its story follows Amelia Vanek (Essie Davis), a harried single mother struggling to raise a son with behavioral issues, Samuel (Noah Wiseman). Amelia’s husband died in a car accident while driving Amelia to the hospital to give birth. As a result, grief overpowers Samuel’s birthday every year, and the difficulties of maternity have Amelia at her wit’s end. One night, she allows Samuel to choose which bedtime story to read. He selects “Mr. Babadook,” a book of unknown origin filled with disturbing content that unleashes a dark entity.

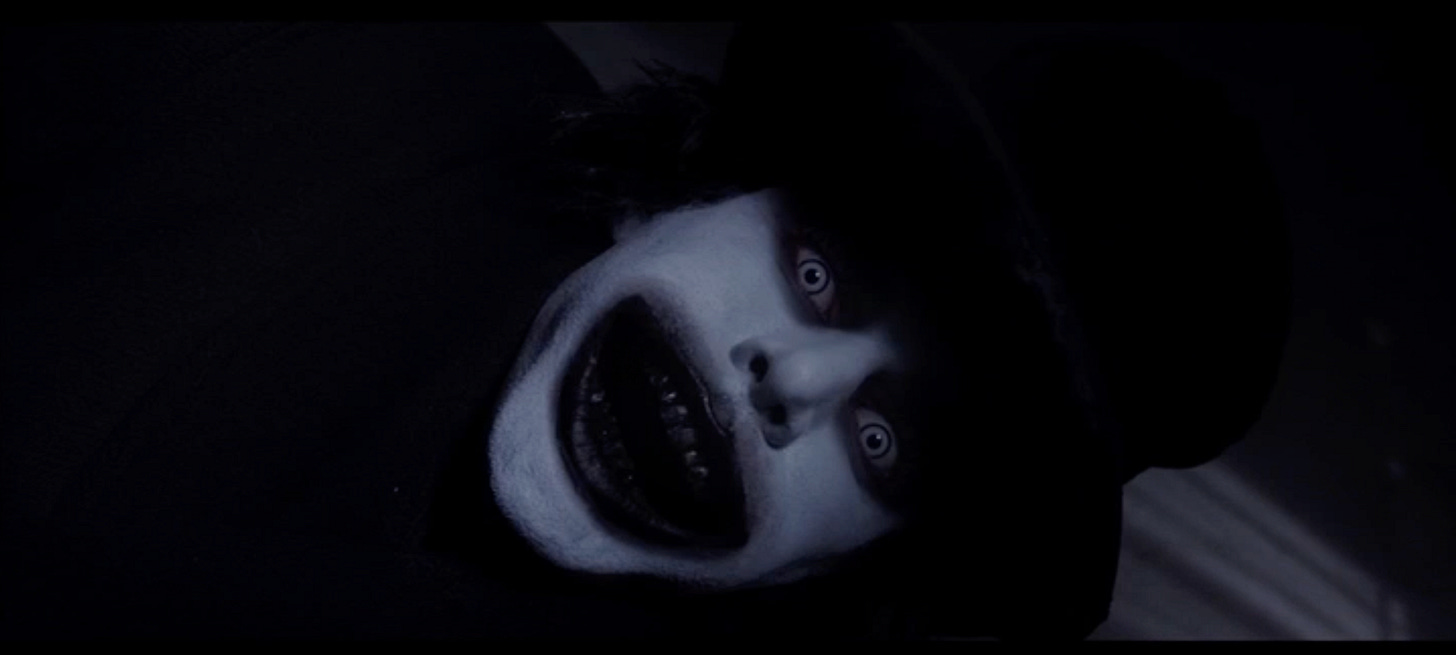

In many ways, The Babadook is functionally identical to The Boogeyman. Both creatures are metaphors for grief, but The Babadook was made 9 years before this summer’s adaptation of King’s short story hit the big screen. Jennifer Kent’s sparse, economical mis-en-scene, chilling sound design, and brilliant creature design result in a film far more terrifying.

“See him in your room at night

And you won't sleep a wink.

I'll soon take off my funny disguise.

(take heed of what you've read...)

And once you see what's underneath

YOU'RE GOING TO WISH YOU WERE DEAD.”

-“Mister Babadook” by Jennifer Kent

Upon first watching The Babadook, the image of the Babadook’s grinning face was seared into my memory. A humanoid creature with a white face and a top hat was one of the most startling monsters I’d seen, and its brilliance draws from the aesthetics of German Expressionism.

A brilliant peer of mine, Ursula, has written an incisive essay about older movies and why their imagery is so unsettling. I highly recommend reading her piece and checking out her publication.

For those that think 'that's just for kids

This 'thing' is not for me'

I urge you not to say those words:

Please take this SEE-rious-LY.

There's just NO WAY you're OFF the HOOK,

If you're ALL GROWN UP when you read this book

And you snub your nose with a civilised look.

You’ll appeal EVEN MORE to the BIG BABADOOK

-“Mister Babadook” by Jennifer Kent

Mister Babadook’s Rainbow Secret

Mister Babadook’s ascension as a queer icon was the result of an internet meme gone awry. Tumblr user “taco-bell-rey” posted a screenshot of The Babadook on Netflix, listed under the LGBT subgenre.

“Mister Babadook, as the figure is referred to in the movie, is queer in the most empirical sense. Its existence is defiance, and it seeks to break down the borders of acceptability and establishment.”

-“How the Babadook became the LGBTQ icon we didn’t know we needed” by Alex Abad-Santos, published in Vox.

Although it began as a joke, there is genuine weight behind a queer interpretation of The Babadook. Kent’s intent was to make a film about grief, that is undeniable. However, much like The Boogeyman in Stephen King’s short story, what The Babadook represents eludes singular classification. Its text, knowingly or otherwise, lends itself to a metaphorical interpretation of grappling with one’s queer identity.

“I’ll WAGER with YOU.

I’ll MAKE you a BET.

THE MORE' you DENY me

The STRONGER I GET!”

-“Mister Babadook” by Jennifer Kent, … on denying queer identity?

I mean, think about it. The Babadook has a flair for the dramatic, wears a top hat, and his existence disrupts domestic life. Samuel is a child who cannot fit into the culture surrounding him. He loves his mother, has a passion for magic tricks, and often wears a sparkly golden cape. Amelia is the angriest with Samuel whenever he attracts the attention of neighbors. It’s as if she’s embarrassed by his difference, unable to cope with the shame.

Regardless of Kent’s intent when conceptualizing The Babadook, his coronation as a queer icon speaks to the fluid nature of artistic interpretation. Jennifer Kent made a movie about grief, and queer people saw themselves and their experiences within that film. That resonance was conveyed via ironic memes, but the text lends itself to an unironic queer reading.

As a queer person, I rarely see my experiences reflected on screen. The preponderance of heterosexual love stories does not resemble any of my experiences. If there are queer characters, they’re often comedic accessories for white women or languishing in misery. Given historic oppression and the ongoing psychological damage of the closet, queer stories pair well with tragedy.

Queer identity has been historically maligned and regarded as a threat to society. Within the horror genre, it’s only natural that queer people would identify with the closeted demon with a flair for the dramatic whose existence disrupts traditional domesticity.

I’ve been in the closet, I know it well. It’s a horrible place to be. Under no circumstances will I go back and, frankly, I see no reason why The Babadook should either. Let that fabulous ghoul slay the house down boots.

Life is so much bigger than the closet. Don’t be like Lester Billings. Face your Boogeyman. Befriend your Babadook. Dive into your fears. Your “demons” will thank you.

Subscribe to Acquired Tastes if you’re an ally. People will know if you don’t.

Help spread the gay agenda!

See you next week, my fellow film freak.

Skylar!!! Thank you so much for the shout-out <3

This was such a great read, though I must say I felt a bit called out by your list at the beginning lol (every one of those items describes me—even the affinity for iced coffee, unfortunately). I've often thought about why it is we like horror so much, and your write-up is easily the best explanation I've seen since this: https://www.youtube.com/shorts/RUGj5cLOW0s

I didn't know you are a big Stephen King fan. Me too! I don't think we ever discussed his work, but he has been a huge influence on my appreciation of horror. I haven't read "The Boogeyman," but it sounds quite chilling. We'll have to catch up sometime on his work. It would be interesting to see if he's done much with queer characters. It's hard to recall many--maybe the primary villain in Dr. Sleep but who else?