Saw is the Horror Genre’s Fast Saga

Earlier this year, I wrote in my review of Fast X:

“The road to Fast X is long and winding. It veers in unexpected directions, oftentimes doubling back to revise, retcon, and retrofit its way toward some semblance of narrative continuity for the franchise as a whole. As the Fast Saga clumsily retrofits its own story, audiences are rerouted into precariously contrived loop-de-loops of soap opera shenanigans. That is because, at its core, The Fast Saga is nothing more than a masculine-coded telenovela. … So, as you can imagine, the narrative continuity of these films is positively fucked. That’s part of The Fast Saga’s charm.”

Saw, it turns out, is very similar. Each installment foregrounds Jigsaw’s cleverly designed traps and torture devices, but Jigsaw’s overarching storyline doesn’t quite fit together.

As the franchise progresses, convoluted flashbacks serve as narrative connective tissue. We revisit the events of previous films from different perspectives, temporal fuckery abounds, and it becomes difficult to understand the events of these films let alone take them seriously.

Saw was a simple film, but the Saw franchise is anything but. It quickly becomes a slapdash Rube Goldberg-esque narrative clusterfuck of soap opera shenanigans. I’ll spare you the details, they’re too convoluted for me to even recount.

Where The Fast Saga’s telenovela tendencies added to the franchise’s charm, the narrative incoherence of the Saw films serves to further alienate viewers. They are, after all, very alienating films. For those with strong enough stomachs, the nonsensical nature of the narrative’s progression forces viewers to lean in, if they have any hope of understanding what the fuck is going on.

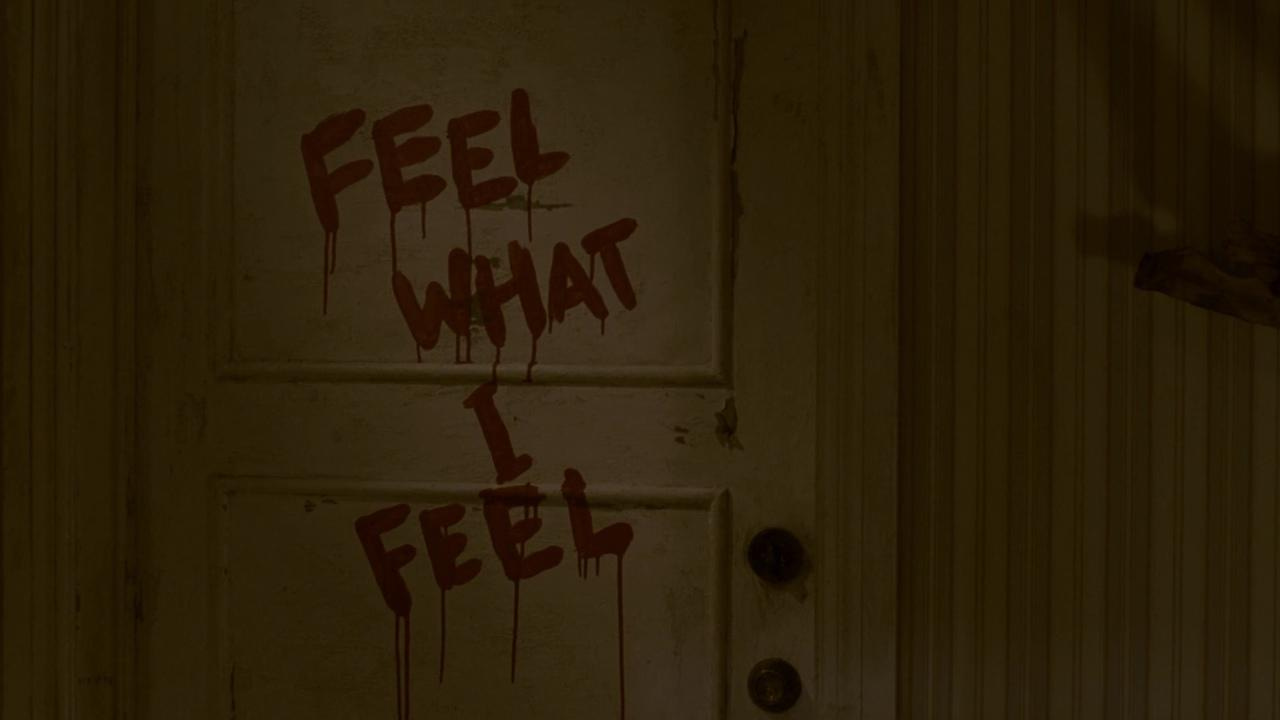

Are the Saw films worth watching? It’s difficult to say yes. Ultimately, I think they’re shallow, subpar films. Am I glad I watched them? Yes. For one, they felt like a right of passage. However, my favorite thing about Saw is each installment’s attempts to develop a theme that can be reduced to a few words. These themes are mostly underdeveloped. They often gesture towards social issues — sometimes concretely, sometimes obliquely. Sometimes it feels like these films actually want to say something but all that’s left is the gory outline of an actual statement.

Why see Saw?

With Saw X entering theaters this Friday, I thought catching up on Jigsaw’s games would be wise. I had never seen the Saw franchise and, frankly, I never thought I’d have the interest. I didn’t foresee my love for horror blossoming. I hadn’t read the scholarship about ‘torture porn,’ which contextualizes the subgenre’s surge in popularity alongside the post-9/11 traumas inflicted on our collective psyche.

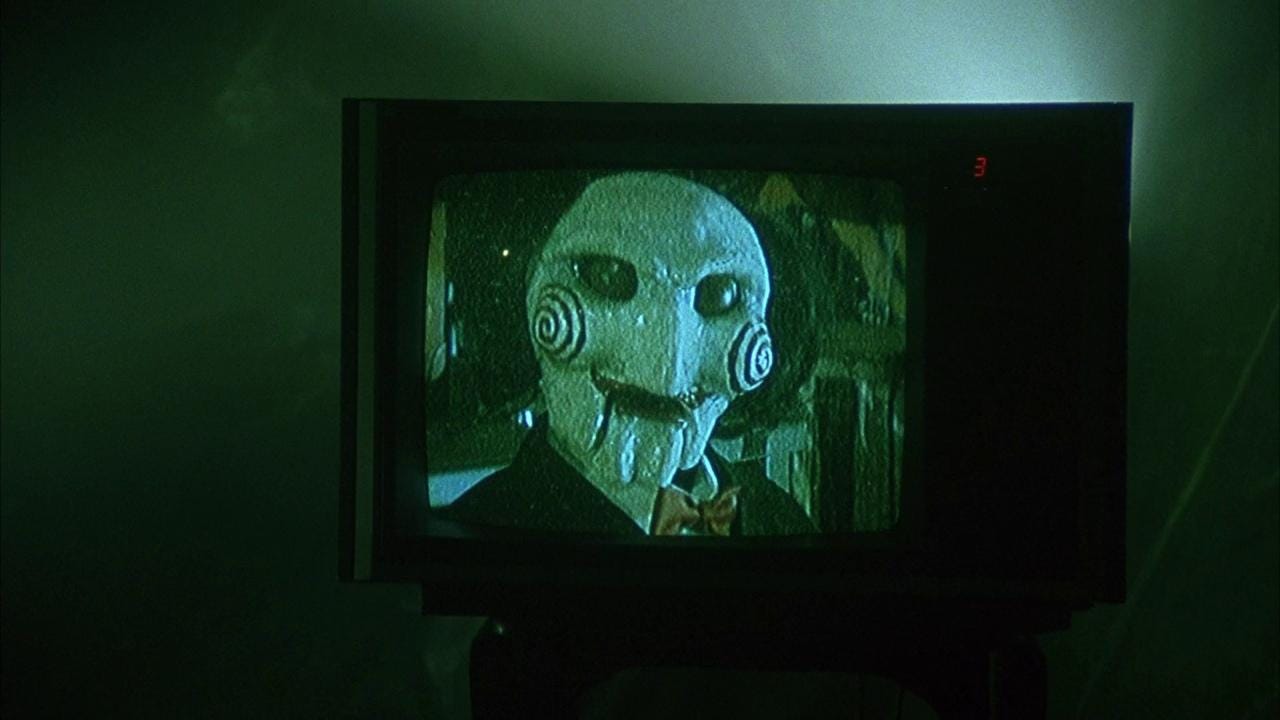

Saw (2004) was released when I was about six years old. Directed by James Wan, the first Saw was divisive among critics. It was a small film: two men chained to pipes, a corpse between them. Most of the film takes place in a single room, the rest is conveyed through flashback sequences. Lengthy, expository flashbacks become a crutch for the franchise, but initially, it was an excusable plot contrivance that allowed the film to cohere like a puzzle coming together — a rather shitty puzzle, but a puzzle nonetheless. The film’s mise en scène was grimy, the editing style was jarring, and the violence was relatively unflinching for mainstream horror circa 2004.

Saw, produced for just over one million dollars, recouped 100x its budget. A sequel was all but guaranteed. Over the next five years (2005-2010), Lionsgate churned out a new Saw film every Halloween. Jigsaw was a staple of the fall box office until I was about twelve. By then, I had been inundated by the annual marketing blitz but was too young and too scared to participate in Jigsaw’s games.

After Saw 3-D (2010), a.k.a. Saw: The Final Chapter, the series retired for seven years. It returned with Jigsaw (2017), a soft revamp that didn’t initially compel my attention. A few years later, Chris Rock would star in Spiral: From the Book of Saw (2021) - a title that suggested little overlap with the main franchise. “From the Book of Saw” confused me. What book? Whatever was going on with these movies, I couldn’t be bothered to figure it out.

This summer I saw a poster for Saw X, and it occurred to me that I would probably want to review that film. I’d like to have a theatrical Saw experience, which was an annual event for a previous generation of horror enthusiasts.

I wanted in on the games, but first I’d have to train. Beginning in August, I watched my way through the entire Saw franchise in preparation for the release of Saw X.

Ranking the Saw Franchise

With that in mind, and in preparation for Saw X’s release later this week, I thought it would be fun to rank each chapter in The Book of Saw.

9. Saw: The Final Chapter - The one about phonies.

Saw: The Final Chapter is the pits. In the seventh installment, as recurring characters make their final moves in the franchises’ grander games, our victim-of-the-week is a self-help guru who provides guidance to survivors of Jigsaw’s games. He’s a fraud that hasn’t ever been targeted by Jigsaw… until now, that is. Will he survive? I don’t know. Do I care? Definitely not.

8. Saw IV - The one about… time?

After three installments, Saw IV is where the wheels start to come off. It’s a film enamored with tricky timelines, weaving in and out of past films. The beginning is the end and the end is only just beginning. Reach exceeds grasp as Saw IV desperately attempts to keep the franchise alive with ambitious story choices that will leave you shaking your head in bewilderment.

7. Jigsaw - The one about confession.

This soft revamp fancies itself a thriller, lessening the violence to attract a new generation of viewers uninterested in the gristle of previous Saw installments. Jigsaw has gathered a group of victims with dark pasts (standard fare for a Saw film) and demands they confess their misdeeds. The stylistic difference is a welcome change, but the violence is only marginally toned down and the film doesn’t amount to much. It’s unmoored in time, less so than Saw IV, but enough to undermine the plot’s progression. Confession is, by the eighth Saw film, a woefully basic theme to be grappling with.

6. Saw V - The one about fair play.

A pendulum threatens to slice a man in half unless he places his hands into mechanisms that will mangle them. He does, supposedly winning his freedom. Despite following the rules, he is sliced in half by the pendulum. Whoever set up this game isn’t adhering to Jigsaw’s sense of fairness. There is no game without a chance to win, a central provision of Jigsaw’s modus operandi. Meanwhile, FBI Detective Strahm escapes near certain death from the water cube by performing a DIY tracheotomy. This auspicious start goes nowhere, as Strahm spends the movie working to uncover information that the viewing audience has known from the start, rendering the whole installment functionally useless.

5. Saw II - The one about justice.

Saw II does what the original does on a larger scale, as sequels do. It is also inferior to the original, as sequels often are. Most of the characters fighting for their lives are one-dimensional, their selfish behavior queuing them up for slaughter. The body count is higher, but the impact is diluted. Donnie Wahlberg's lead performance as Detective Eric Matthews leaves much to be desired.

4. Spiral: From the Book of Saw - The one about police reform.

Chris Rock’s decision to appear in a Saw film was perplexing. After seeing Spiral, I can understand why the project had appeal. A Jigsaw copycat killer is targeting police officers. Spiral features creative traps and violent deaths, but the film feels more like a police procedural than a horror movie. Like so many police procedurals, the end is predictable. Nevertheless, going through the motions is suitably engrossing. The underlying social issue in Spiral is among the franchise’s most compelling, but for all that it grapples with the issue, it doesn’t cohere into a concrete statement or critique. I think that’s a shame.

3. Saw III - The one about vengeance.

Jigsaw needs brain surgery. Meanwhile, a father undergoes a series of trials that allow him the opportunity to exact vengeance on people responsible for his son’s death. Questions of justice and the individual’s choice to forgive exist in tension: the former supposedly impartial, the latter deeply personal. It’s far from a masterpiece, but I felt a twinge of human emotion by the end of Saw III, a major achievement for this otherwise numbing franchise.

2. Saw - The one about survival.

Saw’s salvation lies in its (relative) simplicity. The (a)morality of Jigsaw’s games is introduced in a way that feels novel, seeing as it hasn’t been repeated ten times yet. The intellectual premise is easy to grasp: for those losing the will to live, proximity to death will reignite their will to survive. Jigsaw doesn’t care to kill, he wants to teach people lessons about appreciating life. With your leg chained to a pipe and a hacksaw in reach, how far are you willing to go for freedom? What are you willing to do to survive?

1. Saw VI - The one about health insurance.

Six films deep, I was shocked to find Saw had something to say about the world. I expected more of the same: gallons of blood & pounds of flesh exacted. Imagine my surprise when the film starts explicitly condemning the inhumanity of privatized health insurance, with a particular focus on the lack of protections for people with pre-existing conditions.

Saw VI is a movie of its moment. The film was released in October 2009, when the global economy was brought to its knees as the result of irresponsible trading practices of subprime mortgages and credit default swaps. It was a time when the average American was hurting and directed their ire at Wall Street executives.

As American families were evicted from their homes, executives accrued more wealth. Health insurance companies were allowed to behave with the same criminally callous disregard prior to the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which was passed in March of 2010, and contained pre-existing condition protections.

Before the ACA’s passage, insurance companies were able to deny coverage to any policyholder with a pre-existing condition. For example, you pay Umbrella Health a monthly premium to be enrolled in their program. If you need medical care, Umbrella Health is supposed to cover (at least part of) the cost — setting aside the complexities of copays and deductibles.

Imagine you are diagnosed with cancer. Terrifying, I know. As a cancer patient, you’re going to require expensive medical treatment. In 2009, Umbrella Health would have the legal right to revoke your insurance coverage upon your diagnosis.

“How could that be?” you may ask. Well, it’s a very simple consideration from the perspective of capitalists running insurance companies for profit. Health insurance companies would make more money if they didn’t have to pay for your medical care. So they drop you. It would be more economically advantageous to Umbrella Health for you to just die.

Until 2010, this was an entirely legal practice. Jigsaw doesn’t think that’s fair nor do I. In a veritable screed against the system, Jigsaw punishes a top executive while simultaneously suggesting that the individualized punishment of one executive won’t alter the inhumane landscape of insurance coverage.

Justice and morality clash on individual and systemic levels. There is no clear resolution. Human nature is pretty dismal throughout the Saw franchise, but at least the anger of Saw VI functions as an unambiguous indictment of a real-world system of injustice.

I am left to wonder if Jigsaw would be satisfied with the incremental reforms of the ACA.

I like to think Jigsaw would be a Bernie supporter.

Subscribe to Acquired Tastes for next week’s review of Saw X:

Have you seen Saw? I’d love to know your thoughts.

Until next week, film freaks.

Final line gave me a giggle. The fact that you watched 9 SAW movies so you could watch another SAW movie let's me know you are a true practitioner of movie reviewing....also, would you like a hug?

you're a glutton for punishment, in your completist approach to this nasty franchise--but I enjoyed your writing as always, even if I couldn't sit through any of this dreck