Burton’s Back on His Freak Shit

Beetlejuice Beetlejuice finds director Tim Burton revisiting his macabre masterpiece thirty-five years after its initial release. After a handful of artistic flops, it’s a genuine relief to see Burton back on his freak shit, even if it doesn't constitute a triumphant return to form.

Beetlejuice Beetlejuice finds Lydia Deetz (Winona Ryder) struggling in the spotlight as a television medium. Following the death of her father, three generations of Deetz women return to Winter River, Connecticut, to bury the dead and, perhaps, unleash an old enemy. It's like a cracked-out Gilmore Girls Halloween bonanza.

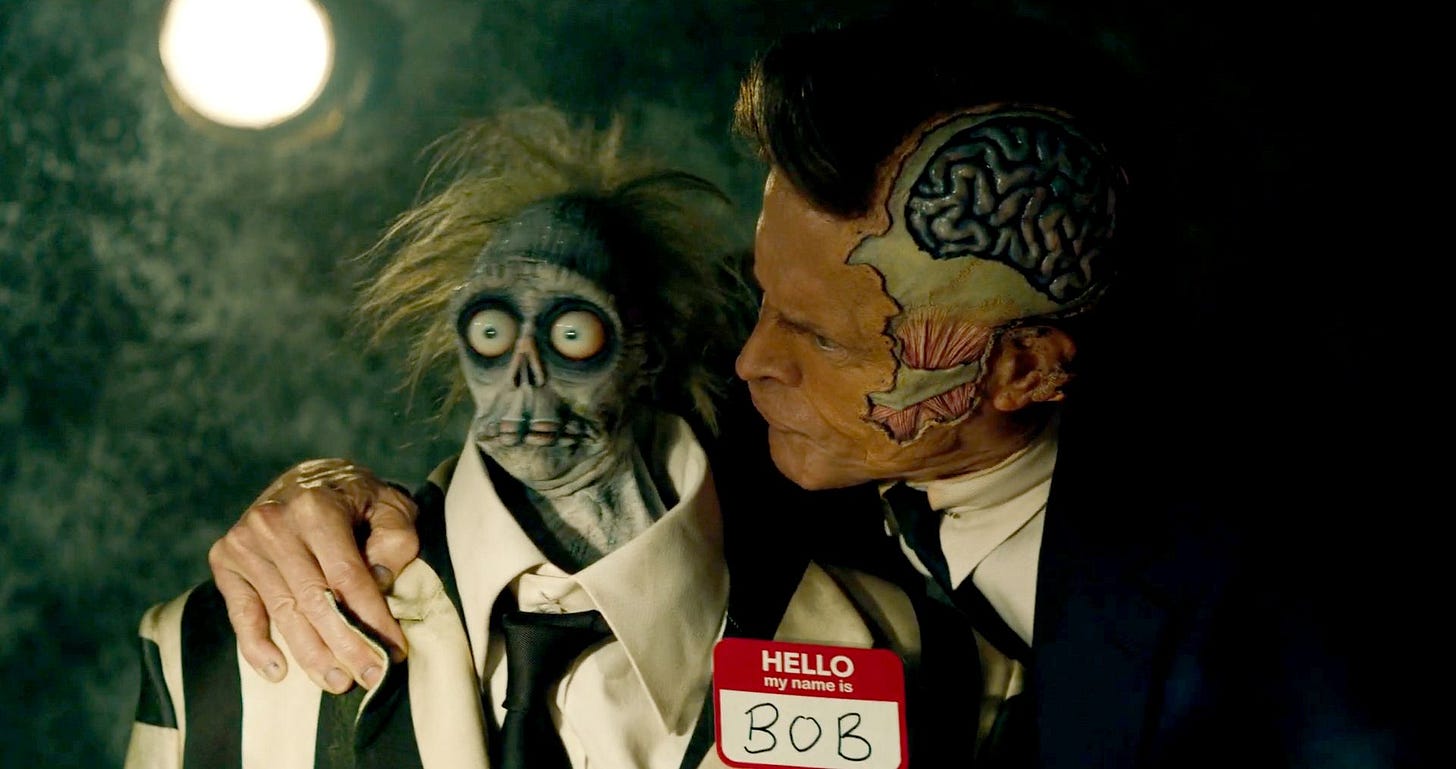

Burton's penchant for the strange and unusual, coupled with a refreshing reliance on practical effects, provides plenty of dreadful sights to delight viewers. However, as the film’s befuddling title suggests, Beetlejuice Beetlejuice is an incomplete incantation that fails to summon even two-thirds of the original’s spellbinding charm.

Over the last fifteen years, Burton has become consumed by the movie-making machinery of the Hollywood studio system, and the value of his artistic stock has plummeted.

As I wrote in my retrospective on Burton’s Planet of the Apes (2001):

His best works have a dark, distinctive gothic luster (e.g., Beetlejuice (1988), Batman (1989), Edward Scissorhands (1990)). There are works of unabashed weirdness, especially towards the beginning of his career, that blossom from pre-existing intellectual properties or historical figures (e.g., Pee Wee’s Big Adventure (1985), Batman Returns (1992), Ed Wood (1994)).

If you fast forward to the 2010s, you’ll notice something about Burton’s filmography has shifted. Alice in Wonderland (2010) is a narrative and visual abomination, Dark Shadows (2012) is a total dud, and a Disney automaton might as well have directed Dumbo (2019).”

A New Phase for Burton

Beetlejuice Beetlejuice marks a new phase for Burton. In the autumn of his career, Burton attempts to rekindle the zany charm of his early output. Thankfully, the film delivers a few moments of unhinged oddity that spice up an otherwise bland witches’ brew.

While Burton’s return to his gory and ghastly roots suggests his distinctive sensibilities still exist within the artist-turned-studio-automaton, it’s only the specter of the visionary director that once was.

There’s something fundamentally off about Beetlejuice Beetlejuice, a film that seeks to build on the original’s legacy by treading familiar ground. To recapture Beetlejuice’s magic, the sequel replicates the original’s most memorable story beats. Nostalgia curdles into empty emulation as the film’s insincerity begins to show.

This is perhaps best epitomized by the choral rendition of Harry Belafonte’s “Day-O” sung at Charles Deetz's funeral. At first glance, it seems like a suitably sullen reference to the original’s most memorable moment: “the Day-O Dinner Scene.”

Then, as a massive fan of the original film, I remembered that it was the Maitlands, Adam (Alec Baldwin) and Barbara (Geena Davis), neither of whom returned for Beetlejuice Beetlejuice, who loved Bellafonte. The “Day-O Dinner Scene” is the Maitlands’ attempt to scare Charles and Delia Deetz out of the house.

Why, then, is Charles interred to the same song? Well, because it was in the original film, so it must be here. It’s a poorly planned form of pandering that pulls into stark relief that Beetlejuice Beetlejuice is a hollow imitation of a far better, genuinely inspired film.

Despite his confidence and competence behind the camera, Burton’s attempts to rekindle the zaniness of his youth feel about as authentic as the artistic works of Delia Deetz (Cathrine O'Hara).

Faces Old and New

O’Hara, a brilliant comedic actress enjoying a professional renaissance on the heels of Schitt’s Creek, gets plenty of screentime given that the film’s inciting event is the death of her husband, Charles Deetz (previously played by Jeffrey Jones, who was arrested in 2002 for soliciting explicit photos from a 14-year-old boy).

Unfortunately, Delia Deetz cannot escape the shadow of Moira Rose, the eccentric failed actress O’Hara played in Schitt’s Creek. Burton’s world doesn’t allow O’Hara to fully spread her comedic wings for fear of overshadowing the rest of the cast.

Winona Ryder does a fine job recapturing Lydia’s gloomy monotone. Jenna Ortega joins the cast as Astrid Deetz, Lydia’s daughter. Of course, it wouldn’t be Beetlejuice Beetlejuice without Micheal Keaton hamming it up as the titular “ghost with the most.”

Italian model and actress Monica Bellucci also joins the cast as Delores, a superfluous character whose inclusion baffled me until I learned that the actress is Burton’s partner. Burton has a history of including his lovers in his work, as evidenced by his numerous collaborations with Helena Bonham Carter until they split in 2014.

The ABCs of Narrative Structure

Dolores’ inclusion necessitates her own plotline within an already overstuffed film. In its attempt to juggle multiple storylines, Beetlejuice Beetlejuice’s script comports with the A-B-C plot structure, which is more common in televisual narratives.

The “A story” will be the primary focus of your story. Meaning it will usually be about the lead and have the most amount of scenes (i.e. screen-time).

The “B story” is generally a parallel storyline headed by more secondary characters.

The “C story” (and deeper in the alphabet), also called a “runner“, are about ongoing/macro stories that pay off long-term (or, in the case of some comedies, quick gag scenes).

In Beetlejuice Beetlejuice, the “A story” follows Lydia, and the “B story” follows her daughter Astrid. These plotlines naturally intertwine in the latter half of the film in a way that the film’s “C story,” carried by Delores, never does.

Television, whose stories must be sustained through serialization, has enough space to develop “runners” over time. Beetlejuice Beetlejuice, clocking in under two hours, juggles too much and ends up dropping the ball. Delores’ “C story” doesn’t have any value whatsoever. She’s not even good for a gag.

Why, then, is Belluci in the film? Ostensibly, because Burton wanted to include her, and so he does. In so doing, he compromised the film’s narrative structure. Beetlejuice Beetlejuice eschews the narrative simplicity of its predecessor and, instead, includes unnecessary roles for Burton’s lovers.

From Life to Death to Life to Death…

Burton, unimpeded, falls victim to his own excess. Too much time is spent in the afterlife, robbing Beetlejuice’s wry bureaucratic conception of life after death of its absurd novelty.

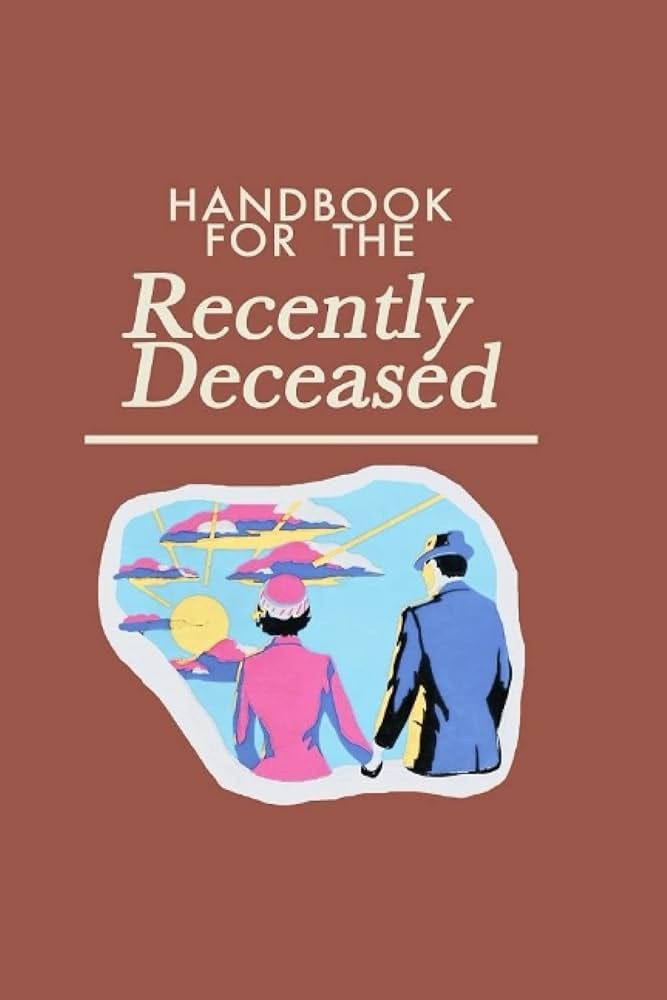

In the original Beetlejuice, the viewer’s perspective is tied to the Maitlands as they struggle to comprehend the afterlife. The darling couple has crossed a bridge (or driven off it, as the case may be) and, now dead, there’s no going back.

They’re still learning the rules from The Handbook for the Recently Deceased, which leaves them susceptible to manipulation by an unscrupulous poltergeist who, over the centuries, has discovered a loophole that will return him to the land of the living. He exploits an opportune connection between life and the afterlife, bridged by Lydia Deetz, a suicidal teen also stuck between life and death. (Teenage suicide: Don’t Do It!)

In Beetlejuice Beetlejuice, it’s clear that the rules are being made up as we go without regard for the broader narrative implications. The boundaries between life and death become muddled as Beetlejuice Beetlejuice whisks its characters from the land of the living to the afterlife and back again.

Returning to Winter River, Connecticut, in 2024, it seems the one-way road from life to death has been widened into a two-way street.

As Beetlejuice Beetlejuice bastardized the boundaries between life and death, I contemplated Hollywood and immortality. In Hollywood, great movies become timeless classics that will outlive their creators. In that regard, Beetlejuice is immortal.

On the flip side, Beetlejuice Beetlejuice is an unwelcome reminder that Hollywood is a business that will do anything to keep a profitable intellectual property alive. In that regard, Burton’s best work is ambling into the 21st century on life support.

Until next week, don’t say his name thrice, film freak.

Burton is what the man whose film biography he made, Edward D. Wood, Jr., would likely have become had he been a better filmmaker and a part of the Hollywood studio system. They share a particular interest and concern with the supernatural relatively few other filmmakers have.