Francis Ford Coppola’s Showgirls

Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis, an ambitious work of philosophical fiction over four decades in the making, landed in theaters this week with a comical plop. It is a humbling reminder that “great” filmmakers don’t invariably produce “good” art.

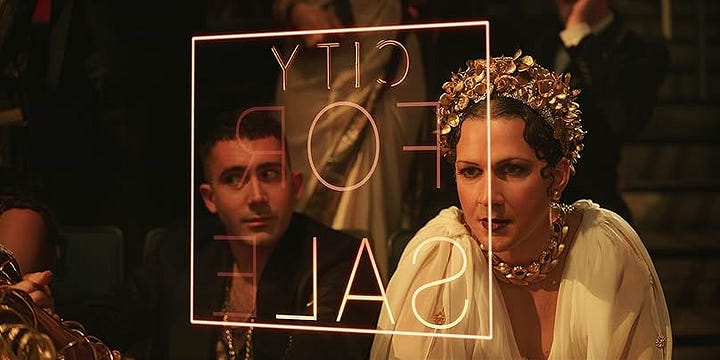

The film sports a gaudy CGI reminiscent of Cats (2019), a befuddling, otherworldly tone evocative of Showgirls (1995), and is powered by intellectual ambitions befitting an Ayn Rand novel (pejorative).

That Francis Ford Coppola sat behind the camera doesn’t change the fact that Megalopolis is philosophical prattle cloaked in the pastiche of prestige. His gilded opus is proof that while you can’t polish a turd, you can certainly roll it in glitter.

At eighty-five, Francis Ford Coppola is entering the twilight of his career. Like so many of us, he looks at the world around him and feels despair. The legendary filmmaker turns to cinema as a means of expressing his worldview, burdened by feelings of confusion and anguish.

I went to a 9:15 p.m. screening of Megalopolis on the Thursday before the film’s official release. The theater, essentially on Emerson's campus, was packed and smelled quite dank. Over the ensuing 138 minutes, the theater resounded with laughter more consistently than any screening in recent memory. The audience’s reaction was raucous and unquestionably derisive.

Megalopolis is a film as ripe for mockery as it is rumination. In that regard, it embodies Acquired Tastes's ethos: a terribly fascinating cinematic shit-heap.

Megalopolis tells the story of powerful men with conflicting visions for the future of New York City, referred to as “New Rome” within the film. In the film’s opening minutes, a block of housing is demolished, setting the stage for a clash between Mayor Cicero (Giancarlo Esposito) and Chairman of the Design Authority, Ceasar Catalina (Adam Driver).

Where Mayor Cicero envisions a casino, Ceasar dreams of building an urban utopia out of “megalon,” a revolutionary bio-adaptive building material he discovered. Meanwhile, jealousy and ambition spur plots to undermine those in power. It is a cautionary tale of outsized egos situated against an empire in decline.

In this regard, Coppola’s Megalopolis practically begs to be put in dialogue with the work of Ayn Rand, a terrible author who used novels to express her terrible ideas, philosophy, and worldview.

I can’t say for certain that Coppola has taken inspiration from Rand’s work, but their overlapping plot elements are difficult to deny. At the very least, Rand’s unconventional approach to storytelling is at play. The subtitle on Megalopolis’ poster labels the movie as “a fable.”

“fable: narrative form, usually featuring animals that behave and speak as human beings, told in order to highlight human follies and weaknesses. A moral—or lesson for behaviour—is woven into the story and often explicitly formulated at the end.”

-Encyclopedia Britannica

In theory, declaring Megalopolis “a fable” clarifies the film's intent. It forces the film to be considered within a framework that stresses the importance of the moral message woven into its narrative over the narrative itself. The ideas within are an end in themselves, and the narrative is merely the means through which they are expressed.

In practice, qualifying Megalopolis as “a fable” functions as an excuse for its incoherence as a cinematic text. Its dialogue is laughably bad, its narrative is disjointed and uncompelling, and its characters and their emotions aren’t relatable or believable in the slightest.

As a work of art, Megalopolis’ execution demands criticism. Coppola inelegantly invokes symbols from the past and present to comment on the prospective future. For example, a charlatan seeking to foment unrest via faux populism gives a stump speech on a literal swastika-shaped tree stump. His supporters carry red signs that say “Make Rome Great Again.” Coppola’s meaning is painfully obvious, but the blunt force inclusion of such symbols pushes the film’s world into absurdity.

I love absurd cinematic fables, as evidenced by my love of The Substance (2024).

A film does not need to reflect reality to offer substantive commentary on current events. I argued that Civil War (2024) successfully renders a chilling portrait of American disunion because its conflict is abstracted from American politics.

By no means was Megalopolis doomed to fail. However, as the distance between recognizable reality and the unqualified absurdity of Megalopolis’ world continues to widen, it becomes increasingly difficult to ascertain, let alone indulge, Coppola’s intent. It is a deeply unserious film that begs to be taken seriously.

Much of Megalopolis gets lost in translation, vacillating between pensive solemnity and unqualified absurdity. It is impossible to fathom what Francis Ford Coppola was thinking while crafting this film, yet decoding his intent is essential to the story’s stated function as “a fable.”

As a self-financed production written and directed by Coppola, Megalopolis also exemplifies auteurism. It stresses artistic intent but is ultimately unable to communicate with any semblance of finesse.

In Coppola’s head, and perhaps even on paper, Megalopolis is more coherent. Rendered via cinema, it’s an unmitigated failure. Perhaps the story isn’t suited to the medium, or perhaps Coppola simply isn’t suited to this type of storytelling.

At the center of his “fable” is a vague entreaty for hope and the preservation of idealism, mired in misguided absurdity and undermined by an encroaching sense of nihilism. Coppola’s fable ultimately lacks the clarity or temerity to offer a coherent lesson. In that regard, it isn’t much of a fable at all.

The film waffles on about time, love, and human nature. It occasionally poses intriguing questions like, “Is this society, is this where we're living, the only one that's available to us?”

It’s a fable that refuses to answer its own questions, instead asserting that “when we ask these questions, when there's a dialogue about them, that basically is a utopia.”

It’s a text whose deeper meaning, to the extent that there is any, demands multiple viewings to be decoded.

However, as Megalopolis keenly points out, the world is falling apart, and time is passing me by. Am I meant to spend my precious time pouring over Megalopolis in search of meaning?

No, I think not.

Megalopolis is philosophical schlock from one of the biggest names in contemporary cinema: a terribly interesting failure that must be seen to be believed but arguably isn’t worth seeing because, well, it’s a terrible movie.

Fantastic review! I just saw the film and, sadly, have to agree with everything you said so well here. Funny and articulate as always.

My extremely negative Boston Globe review has gotten some pushback from my film critic brethren, who say that I disrespected Coppola. I didn't know I was obligated to respect him. He ain't my daddy, and if he were, I'd be pissed off that he spent my inheritance on THIS wretched, unredeemable hot mess. I despise the film criticism world's desire to give these old White dude directors a pass no matter how crappy their films are. I have no such desire. I could care less that he's 85 and spent his own money. At TIFF, all he did was WHINE like Trump about how he was a victim.

The one thing I'm grateful for after watching this film is that I now realize how misogynistic much of FFC's canon is--even the good movies. And maybe you can explain to me just what Cesar's Xanadu-style Glow city was supposed to accomplish. Rich dude Coppola is so out of touch with poor people that his proletariat bears no semblance to reality. That makes his "social statements" ring hollow.

I expect drag queens to start doing Wow Platinum imitations any day now.